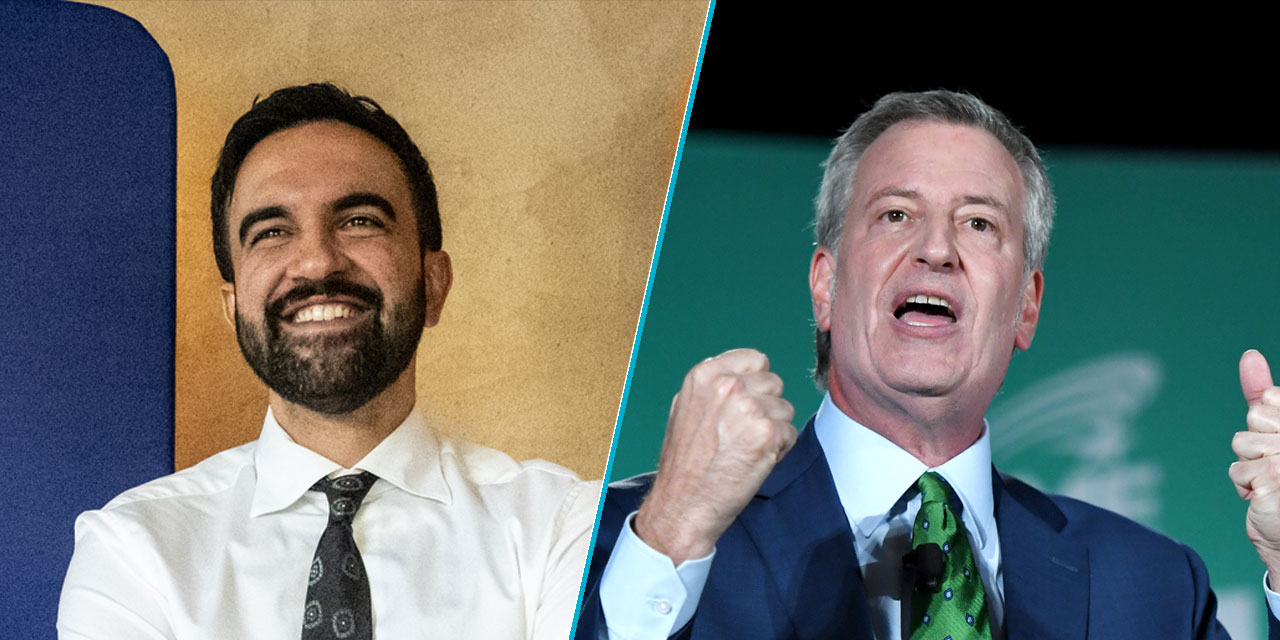

Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral platform is full of sweeping proposals: public grocery stores, rent freezes, and major new spending. Former mayor and fellow arch-progressive Bill de Blasio’s time in City Hall shows how quickly big plans like these can collide with structural limits, flawed policy design, and unplanned events.

In January 2014, de Blasio inherited Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s New York. Crime stood at historic lows, the population was growing, and the economy had rebounded from the 2008 crash faster than much of the country. But the gains were uneven. Inequality ranked among the highest in the nation, homelessness had reached record levels, and the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk practice had become a national controversy.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

De Blasio’s “Tale of Two Cities” campaign for the mayoralty was built on big plans: fight inequality, fund universal pre-K with a millionaire’s tax, end stop-and-frisk, and launch the most ambitious affordable-housing program in city history. Eight years later, de Blasio’s second term had been consumed by rising crime, the Covid-19 pandemic, and protests that exposed his weak leadership.

The creation of universal pre-K early in his first term was de Blasio’s biggest success, but the way it came about also revealed the limits of a progressive mayoralty. De Blasio sought to tax the wealthy to fund the program, but state legislators rejected his millionaire’s tax in 2014, an election year. Governor Andrew Cuomo then moved to fund the Pre-K program from the state budget instead. Families saved thousands of dollars a year on childcare, but the city lost both a dedicated revenue stream and political leverage. Even de Blasio’s biggest win was reshaped in Albany.

His housing policy revealed deeper flaws. Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) tied affordability mandates to rezonings. This policy added costs that stalled projects in weaker markets and deterred rezonings in stronger ones. De Blasio concentrated rezonings in lower-income, less politically resistant areas, leaving transit-rich, high-demand neighborhoods untouched. Rising costs, entrenched opposition, and uncertainty over the 421-a tax abatement (an incentive for developers to build more affordable units) further slowed construction. MIH produced only a small share of the affordable housing the city needed, leaving rents to climb far faster than incomes.

Policing followed a similar arc. De Blasio curtailed stop-and-frisk, but tried to balance reform with public safety by bringing back Bill Bratton as commissioner. That balance quickly wobbled, with Bratton challenging some changes and police unions accusing the mayor of undermining the force. In 2020, after George Floyd’s death and mass protests amid the pandemic, de Blasio’s progressive policing approach ran out of steam, and voters emphatically rejected his skepticism of policing by electing a retired police officer, Eric Adams, mayor on a law-and-order platform.

Some of the circumstances that defined de Blasio’s mayoralty had nothing to do with his campaign plans. ThriveNYC, a $1 billion mental-health initiative led by his wife, Chirlane McCray, drew criticism for its vague goals, opaque budgets, and questionable spending. His rivalry with Cuomo—fueled by their overlapping authorities and mutual distrust—shaped city policy on everything from housing to mayoral control of schools to pandemic management. Economic growth kept tax revenues high but drove up housing costs, as supply lagged far behind job growth.

Donald Trump’s 2016 victory galvanized a new wave of progressive organizing in New York. Membership in the Democratic Socialists of America surged, fueled by disillusionment with centrist Democrats and a hunger for structural change on housing, policing, and the economy.

By the end of de Blasio’s second term, DSA-backed candidates were winning city council, state legislative, and congressional races, reshaping the city’s political map and making positions that were bold in 2013 seem cautious by decade’s end—and paving the way for figures like Zohran Mamdani, himself a DSA member.

If elected, Mamdani will face many of the same structural constraints that de Blasio did, if not necessarily the same personal antagonism with Albany that marked the Cuomo years. Governor Kathy Hochul shows little interest in public feuds, but state control over revenue, taxation, and core regulatory powers still constrains a mayor’s freedom of action.

Signature proposals will run up against the limits of state control. Housing policies that burden rather than free the market will fail to reduce rents. The first major protest—whether over immigration, budgets, or land use—will test Mamdani’s ability to keep order without fracturing his coalition. And issues he hasn’t campaigned on, and events no one anticipated, will make demands on his time and resources, as they always do.

De Blasio left office deeply unpopular, with his tenure defined less by the promises that won him office than by unrelated events. If elected, Mamdani will face a hostile White House, budget gaps, a wary business sector, and a public concerned about disorder. His campaign promises, like those of his predecessors, will be shaped by state politics, market realities, and unpredictable crises.

Photos: Stephanie Keith/Getty Images (left) / Ethan Miller/Getty Images (right)

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link