On a temperate April night, Detroit was buzzing. The historic Detroit Athletic Club—long a favorite for family celebrations—was fully booked. At the Detroit Opera House, director Yuval Sharon’s reinvention of Mozart’s Così fan Tutte played to a sold-out, enthusiastic crowd. Downtown at Cliff Bell’s, a jazz quartet performed for a racially mixed audience. At Little Caesars Arena, 20,000 fans watched the Detroit Pistons battle the New York Knicks in the NBA playoffs. And along the newly restored RiverWalk, residents strolled the scenic, carefully landscaped waterfront.

Just a dozen years ago, none of this would have seemed possible. Detroit was, as Donald J. Trump recently put it, “a mess”—the nation’s most notorious symbol of urban decline. After the devastating 1967 riots, which left 43 people dead, and the city’s 2013 bankruptcy—the largest municipal failure in U.S. history—downtown Detroit had become a ghost town. Crime rates were soaring. Roughly 200,000 residents and businesses had fled the city over the previous decade, with some estimates putting the exodus at 1,000 people per month. Half the city’s streetlights were out. Arson was rampant, with as many as 12,000 fires set each year. Tens of thousands of homes—about 47,000, by some counts—stood burned-out or abandoned.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

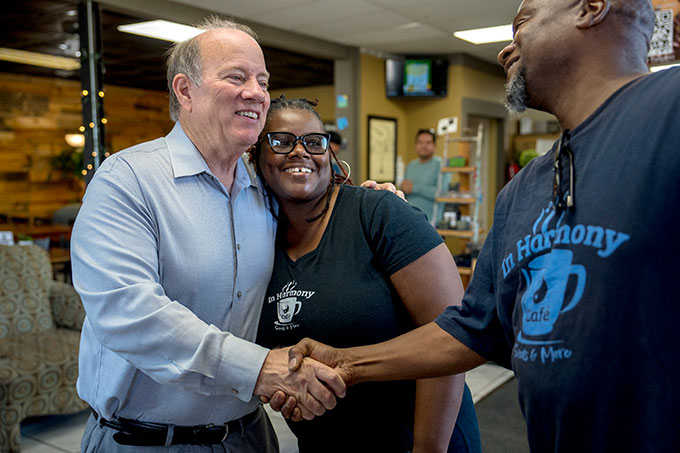

In 2013, Mike Duggan—a former county official and hospital executive—was elected mayor, improbably, as a write-in candidate. He was the first white mayor in nearly 40 years to lead the city, whose population had become predominantly black and whose political culture for decades had been dominated by a Democratic Party race-and-patronage machine that thwarted reform at every turn. Duggan somehow prevailed over this machine and went on to win two more terms. Twelve years later, he has helped drive—again, improbably—one of the more promising urban turnarounds in the country. While Duggan credits others for the city’s revival, he clearly played a central role. Governing magazine recently named him “America’s Most Effective Mayor,” and his leadership offers lessons for other cities struggling with debt, crime, and government dysfunction.

In an interview, Duggan—a Democrat now running for Michigan governor as an independent instead of seeking a fourth mayoral term—said that his greatest contribution to reviving the city where he was born and raised, long known for its fractious politics and racial strife, was “getting people to work together.” Throughout his three terms, Duggan has prioritized collaboration between the public and private sectors. In 12 years as mayor, he has never once vetoed a city council action. “We work things out,” he said. Businesses have returned to Detroit, he added, “because they know they will not be attacked by the city council.”

Yet whether the revival will continue without him is uncertain, according to several of Detroit’s civic leaders, politicians, and business figures, who spoke in interviews on the condition of anonymity. Duggan achieved his remarkable three-term run in a city that, like numerous others in the U.S., has faced decades of decline because of the emergence of a political culture—enabled and deepened by the flight of white residents—that left the remaining residents consistently voting against reform in favor of a politics based on racial and ethnic grievance. This dynamic, which economists Edward Glaeser and Andrei Shleifer have dubbed the “Curley Effect” after the early-twentieth-century Boston mayor James Michael Curley, who first implemented it, still pertains in Democratic-run cities including Newark, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Camden, Chicago, Los Angeles, Baltimore, and Milwaukee. Detroit will elect a new mayor this November; for the city’s recovery to continue, Duggan’s successor must carry on the work he started.

At least for now, the Motor City is back. For the first time since 1957, Detroit’s population is growing. A city $18 billion in debt when Duggan took office now holds $550 million in reserve funds. Once rated as junk, Detroit’s municipal bonds have been upgraded ten times in as many years. Unemployment has fallen from a high of 20 percent in 2020 to below 5 percent. The city’s budgets have been balanced for 11 consecutive years.

Crime rates have plummeted—a key factor in attracting new investment and residents. The city’s homicide total now stands at its lowest since 1965, falling from 252 in 2023 to 203 last year, a 19 percent decline. According to this year’s first-quarter numbers, carjackings and nonfatal shootings are down 30 percent and 45 percent, respectively, compared with the first quarter last year. As City Journal reported in March, initiatives like Project Green Light—a public-private partnership that helps businesses in high-crime areas install security cameras—have played a key role in improving public safety.

“Crime rates have plummeted—a key factor in attracting new investment and residents. The city’s homicide total now stands at its lowest since 1965. ”

But in his final State of the City address and in a follow-up interview, Duggan emphasized that hiring more police at higher pay was critical to reducing crime. When he took office, officers were making as little as $15 an hour, often working 12-hour shifts. Detroit had fewer cops on the streets than it did in the 1920s. Yet unlike many other cities, Detroit did not defund its police department after the 2020 killing of George Floyd. “We gave officers a $10,000 pay raise and put 350 more officers on the streets,” Duggan said. As a result, he says, “[we] got people who should have been locked up locked up.” Duggan also invested $10 million in the city’s community violence-intervention program, which enlists trusted neighborhood activists to work directly with gang members and other high-risk individuals to prevent violence.

Duggan rebuilt the city’s fire department, too, and cross-trained firefighters to serve as medical first responders. A department once notorious for having the nation’s worst response times beat the national average last year by seven minutes and 30 seconds.

Another major challenge was Detroit’s stock of 47,000 abandoned or uninhabitable houses and more than 50,000 vacant lots, which the city’s Land Bank had inherited. In his State of the City address, Duggan credited Erica Ward Gerson, a retired Skadden Arps attorney, with helping reduce the inventory of vacant houses to 2,900, projected to be down to 1,000 by year’s end.

The city demolished 29,000 unsalvageable homes, and the Land Bank launched programs to sell fixable properties—not to developers but to individuals willing to restore them. In just over a decade, one auction program sold 15,000 houses, some for as little as $1,000, to city employees, veterans, and residents, who committed to rehabilitate them within a certain time frame. The Land Bank also sold 25,000 side lots to neighboring homeowners, who turned them into gardens, built garages, or installed basketball hoops and playgrounds. These grassroots improvements boosted property values and helped prevent illegal dumping and other blight-related crimes. Thanks to the Land Bank’s efforts, “whole streets have been saved,” said Duggan. He added that Gerson had run the Land Bank for a decade, as a volunteer. Duggan “bought me a Diet Coke once or twice a year,” Gerson joked.

Duggan has also worked with the city council, state and federal agencies, private companies, mortgage lenders, and philanthropists to expand affordable housing across Detroit. Over the past six years, 92 new housing developments—worth a combined $1.3 billion—have been built. According to Duggan, Detroit now leads southeastern Michigan in the number of new housing units.

The demand is now there. Over the past decade, real-estate values in Detroit have risen faster than in any other major U.S. city. According to the mayor’s office, Detroit homeowners have gained $4.6 billion in property value over the last ten years, including $700 million in 2023 alone. Over 70 percent of those gains went to black homeowners—the longtime residents who stayed. At the same time, tax revenues have climbed steadily, rising 7 percent annually for 11 consecutive years, even as the city has cut property-tax rates.

Duggan took an unorthodox approach to attracting business investment. Instead of offering up-front cash incentives, Detroit has provided generous tax breaks—but only after projects are built. One of the biggest deals came when Ford Motor Company proposed investing over $950 million to restore the city’s long-abandoned Michigan Central Station, one of the city’s most beautiful Beaux-Arts structures, and to surround it with a 30-acre innovation district. The city approved tax breaks worth about $100 million over 35 years for the project. The restored station and innovation center reopened in summer 2024 to critical acclaim and commercial success.

Support from Detroit’s most prominent businesses and philanthropists—long a feature of the city’s civic life—has also been key to its revival. Consider Dan Gilbert, Detroit’s largest private employer, with more than 17,000 employees at his mortgage lending firm, Rocket. Through his businesses and foundations, Gilbert has invested over $500 million in his hometown. In 2010, he helped jumpstart downtown’s recovery by moving Rocket’s headquarters and 1,700 employees to the city center. When the Detroit Land Bank launched its Rehab and Ready program to restore vacant homes, Gilbert provided a $10 million revolving construction loan to get it started. He also committed another $15 million to wipe out property-tax debt for some 20,000 low-income homeowners—an effort that helped preserve an estimated $400 million in household wealth and home equity.

The Detroit Institute of Arts is world-renowned for its collection of 66,000 works, including Diego Rivera’s iconic mural celebrating industrial labor. But when Detroit filed for bankruptcy in 2013, the museum faced the unthinkable prospect of selling parts of its collection to help pay off the city’s creditors, including bondholders and pensioners. In response, the state of Michigan, local philanthropies, and museum donors united in a landmark “grand bargain.” They raised over $800 million to shield the collection from liquidation and to ease the city’s exit from bankruptcy. The deal also restructured the DIA as an independent nonprofit, legally separate from the city, to protect its holdings from future financial crises.

“Art and culture, when they’re quality, bind people to place and to each other, and so are essential in building community,” says Alberto Ibargüen, former president of the Knight Foundation, who helped forge the “grand bargain.” While many others deserve credit—including the Ford Foundation, which pledged $125 million of the $366 million raised by local and national philanthropies—much of the success is attributed to Judge Gerald Rosen, the chief mediator in the bankruptcy case, who played a central role in brokering the agreement that preserved both Detroit’s finances and its cultural legacy.

When Detroit’s local opera company struggled to find new leadership after a fruitless four-year search, local philanthropist Gary Wasserman stepped in. In 2020, he persuaded Yuval Sharon—one of the nation’s most innovative opera directors—to leave Los Angeles for Detroit. Nicknamed the “disruptor-in-residence,” Sharon, now 46, quickly staged bold productions that drew national attention and critical acclaim. Sharon is slated to direct Tristan und Isolde at New York’s Metropolitan Opera next season, followed by a full staging of Wagner’s Ring cycle the year after. Under his leadership, Detroit’s small, financially fragile opera company has earned a spot on the national cultural map. When the Covid-19 pandemic forced the company to close its opera house, Sharon staged a condensed version of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung in a parking garage. Because the company couldn’t afford his salary at first, Wasserman quietly covered Sharon’s initial five-year contract.

Detroit’s outstanding museums, recreation centers, and casino have also helped boost tourism. The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation—opened to the public in 1933 and located on 250 acres in neighboring Dearborn—draws about 2 million visitors a year. With an annual budget of $91 million and a combined paid and volunteer staff of 800, the museum houses a remarkable collection of historic and modern artifacts, including the limousine in which President Kennedy was assassinated and the blood-stained theater seat from Abraham Lincoln’s murder. It also boasts a nationally recognized studio glass collection, second in size only to that of the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York.

Detroit’s Motown Museum, a must-visit for music lovers, celebrates the city’s role in shaping American music through Motown Records, which helped launch the careers of the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, the Temptations, and the Jackson 5. The museum’s centerpiece is Studio A, where many iconic hits were recorded. A $75 million expansion of the museum is currently under way.

Alongside billions in new investment, Detroit has also attracted a new wave of cultural creators like Sharon. For years, residents worried that the city’s revival was confined to downtown. But neighborhoods like Little Village are now showing signs of renewal. There, a deconsecrated 110-year-old Romanesque church—closed since 2016—has been transformed into The Shepherd, a vibrant art gallery and cultural campus featuring work by black and other local artists. Time magazine recently named it one of the “World’s Greatest Places.”

“Detroit still faces daunting challenges. The most imposing of all is finding a successor to Duggan who will build on his reforms.”

The 3.5-acre campus, created by Detroit native Anthony Curis and his wife, JJ, features a bar called Father Forgive Us, an upcoming restaurant from James Beard Award winner Warda Bouguettaya, a bed-and-breakfast, a skate park, and sculptures by the late Detroit artist Charles McGee. Nearby, two nonprofits have moved into a long-abandoned bakery, and a local print shop now sells posters and teaches young Detroiters the craft. A new marina is rising along the nearby riverfront. “We’re committed to Detroit and its future,” says JJ Curis.

Detroit still faces daunting challenges. Geographically vast—134 square miles, into which Manhattan and Boston would both fit—Detroit remains among the nation’s poorest cities. A third of its residents still live in poverty, as do nearly half its children. (Detroit is ringed by wealthy, overwhelmingly white suburbs like Grosse Pointe and Bloomfield Hills, whose taxes finance their own schools and institutions, not Detroit’s.) At least 25 percent of the city’s economy is tied to an auto industry that has been shrinking and now faces an uncertain future due to automation and, more recently, Trump’s tariffs on Canadian auto parts, upon which the city’s three large auto-assembly plants depend. “Business needs predictability,” said Duggan, who added that he supports tariffs, but only if judiciously imposed.

But the most imposing challenge of all is finding a successor to Duggan who will build on his reforms. Will the long-entrenched political culture of racial politics reassert itself and roll back the progress that the city has made? It’s already happened once before. In 1994, reformer Dennis Archer succeeded Coleman Young, whose calamitous 20-year tenure saw the city become a national symbol of urban decline and failure. But after two terms, Archer was succeeded by Kwame Kilpatrick, the rapper mayor considered more “authentic,” who wound up getting removed from office amid criminal charges. This same pattern has been seen in other cities, where a relative moderate pursues reforms for a time, only to be followed in office by a new champion of the old racial politics. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in cities over the last decade, especially after 2020 with the George Floyd riots, intensified this pressure in cities like Chicago and Los Angeles, which have both elected antireform mayors.

Duggan’s past victories offer some cause for optimism in this context. He won reelection, in 2017, by a landslide over none other than Coleman Young Jr.—a perfect example of the old political culture rearing its head. He won reelection again in 2021 by another landslide margin—this, after the tumults of 2020, which did not affect his popularity. What direction will Detroit take after Duggan? The answer will start becoming apparent after August 5, when the city holds its Democratic primary.

But while some worry about what comes next, Duggan insists that the revival will outlast his tenure. The city has a balanced budget, a financial cushion, and 9,000 employees, who, he says, have learned what works—and what doesn’t. “When the Final Four comes here in 2027,” he adds, “I’ll be cheering. Nothing stops Detroit.”

Top Photo: The city’s newly restored RiverWalk has proved popular with residents. (Carlos Osorio/AP Photo)

Source link