The 2025 UN Ocean Conference put Marine Protected Areas at the heart of global ocean action, but global progress hinges on whether the United States steps up to lead.

From June 9–13, Nice, France, hosted the third United Nations Ocean Conference, co-organized by France and Costa Rica, convening over 14,000 delegates from 175 countries, according to IISD reporting. Delegates from different countries, including heads of state, government officials, Indigenous leaders and local communities, scientists, NGOs, financiers, and activists, convened with a shared mission: to accelerate ocean action and fulfill Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14. The backdrop was sobering. Despite past promises, only eight percent of the world’s oceans are under some form of protection, and just three percent are fully safeguarded from extraction or degradation.

The conference succeeded in capturing headlines and raising ambition, but the real question is whether it marked a turning point or merely another fleeting wave of rhetorical momentum. And more crucially, where does the United States stand in this moment of global transition?

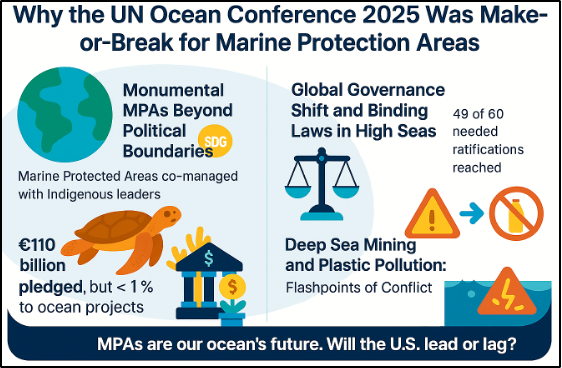

Monumental MPAs Beyond Political Boundaries

Among the most powerful announcements was French Polynesia’s declaration of a new Marine Protected Area (MPA), covering more than 1.9 million square miles of ocean territory, with some portion designated as no-take and another half a million square miles pending before mid-2026. This development now represents the largest MPA in the world, surpassing the United States’ own Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Meanwhile, the Indigenous-led Melanesian Ocean Reserve was introduced as a groundbreaking regional MPA model, bringing together Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and New Caledonia to jointly manage an area nearly the size of the Amazon Rainforest. These declarations reaffirm that MPAs are more than lines on a map, they are geopolitical signals, ecological lifelines, and economic tools.

Yet scientists at the conference emphasized that not all protections are created equal. Marine Protected Areas only yield biodiversity recovery, food security, and climate benefits when they are effectively enforced. This situation requires surveillance technologies, vessel patrols, community stewardship, and legal clarity. Fully protected MPAs are known to increase fish biomass, protect key species, boost reef resilience, and even contribute to carbon storage in seabed sediments. But some MPAs are mere nomenclature known as “paper parks” and may offer little more than political cover.

Global Governance Shift and Binding Laws in the High Seas Treaty

The legal backbone of expanded Marine Protected Area coverage was also under the spotlight. The nearly finalized High Seas Treaty, also known as the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Treaty, saw significant progress during the conference, reaching 49 of the 60 required ratifications for it to enter into force. If this threshold is met by the end of 2025, the treaty will allow for the legally binding creation of MPAs in international waters, which make up two-thirds of the ocean’s surface. It would also regulate marine genetic resource access, scientific research zones, and impact assessments, ushering in a new era of international ocean governance. United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres described it as “The ocean has given us so much. It is time we returned the favor.”

Deep‑Sea Mining and Plastic Pollution: Flashpoints of Conflict

Outside of protected areas, two flashpoint topics dominated debate: deep-sea mining and plastic pollution. A strong bloc of 37 nations, including France, the United Kingdom, and numerous Pacific Island states, called for a global moratorium on deep-sea mining, citing mounting scientific evidence of ecological risks, species loss, and carbon disruption. In April 2025, President Trump signed an executive order authorizing the acceleration of seabed mining permits in both domestic and international waters. This position places the United States squarely at odds with the emerging global consensus for precautionary governance.

On plastic pollution, the conference reaffirmed global urgency. Over 90 countries renewed their commitment to finalize a legally binding Global Plastics Treaty in 2025, with negotiations set to resume in Geneva this summer. This treaty aims to cut plastic production, ban certain polymers, and create circular economic systems for reuse. With around 11 million metric tons of plastic entering the ocean each year, the scientific community has sounded the alarm. Yet the United States remains largely on the sidelines of this initiative, limiting its engagement to observer status.

Financing the Blue Frontier

Financing also emerged as a central concern. The conference secured around €10 billion in pledges, including €3 billion from the European Investment Bank and the Asian Development Bank to combat ocean plastic, $2.5 billion from Latin America’s CAF to invest in sustainable marine infrastructure, and additional support for conservation efforts in West Africa and Costa Rica. However, private investment in ocean protection remains dismally low, capturing only a small share of global climate finance. Investors cite unclear regulations, a lack of standardized data on ocean health, and limited enforcement mechanisms as major barriers to engagement.

Since global capital is pivotal to implementing Marine Protected Areas, the United States, home to major asset managers and green finance innovators, has a vital role to play by developing standardized blue bonds, reef insurance programs, and carbon-linked credits tied to marine restoration, transparent marine ecosystem accounting initiatives, and public-private blended finance instruments. These initiatives will allow the United States to legitimize and expedite ocean investments on a global scale.

America’s Crossroads and Subnational Momentum

Against this complex backdrop, America faces a strategic dilemma. While US scientific institutions such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), and Scripps Oceanography are global leaders in ocean monitoring, data science, and fisheries research, more federal policies and support are crucial to advance science, technology, and innovation and ensure sustainable ocean science and development. President Donald Trump’s rollback of protections for marine monuments, along with his executive order that opens up sensitive waters to fishing and exploration, has raised alarm across the international community. Critics argue that this approach might undermine decades of conservation progress.

Yet a United States pivot is still possible. States and territories such as California, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico could champion regional MPAs through coastal zoning, blue carbon deals, and partnerships with Indigenous groups and local communities. Federal agencies and philanthropic players might align with global standards, integrate MPA metrics into national climate strategies, and convert funding to ensure enforcement capacity.

Marine Protected Areas as Pillars of Sustainability

Perhaps most importantly, the United States must connect ocean protection to its economic and security interests. Marine Protected Areas do not just save fish—they protect shipping lanes, stabilize fisheries-dependent economies, and preserve biodiversity hotspots vital for pharmaceutical and biotech innovation, serving as catalysts for sustainable economic development. Fully protected MPAs can also function as living climate infrastructure, buffering coastlines from storms, sea level rise, and erosion. Moreover, MPAs boost ecotourism, support scientific enterprises, and safeguard coastal communities against climate impacts. Models from Palau to Belize show that MPA-linked fisheries and tourism can generate sustained, equitable income streams.

The spillover from MPAs can replenish neighboring fisheries, raise yields, and stabilize fish stocks, increasing catches by up to 25 percent, debunking the false dichotomy between conservation and commerce.

If the United States, with its advanced maritime infrastructure, legal and financial systems, and global scientific presence, can fully embrace the MPA opportunity, it can spearhead a high-integrity, sustainable blue economy. This would further reinforce national economic resilience and provide a powerful model for emerging ocean economies worldwide.

From Global Promise to National Action

The Nice 2025 Ocean Conference was a turning point—not because it produced statements, but due to its emphasis on delivering measurable, enforceable, and equitable protection. Despite breakthroughs in MPA designation, plastics treaties, deep-sea mining moratoria, and blue finance, the value of these achievements will depend on whether governments and societies convert commitments into action.

For the United States, this expectation demands bridging the gap between domestic policy and global leadership. By ratifying international treaties, reversing counterproductive orders, aligning investment, and empowering coastal communities, it can rekindle its scientific authority and strategic influence across ocean diplomacy, conservation, and a sustainable economy.

Ultimately, MPAs are more than conservation zones—they’re litmus tests of collective will, bridges between science and policy, and engines of a healthier, more just, and prosperous ocean future.

A Call to Conscience

The 2025 UN Ocean Conference delivered bold declarations; however, ambition alone is not enough. Without funding, enforcement, political will, and inclusiveness, blue resources sustainability, especially marine protections, will remain aspirational.

The conference revealed that the world is finally serious about protecting its oceans. The question is whether the United States is willing to swim with the tide—or continue standing on the shore while the world surges ahead. However, the world needs the United States as the ocean leader to support and empower others.

About the Author: Dr. Isa Elegbede (PhD)

Dr. Isa Olalekan Elegbede (PhD) is a US-based marine environmental scientist, ocean sustainability advocate, and policy advisor with over a decade of international experience at the intersection of deep-sea governance, environmental sustainability, and blue economy development. He is a globally recognized voice on deep-sea mining governance, marine biodiversity protection, and the ethical use of ocean resources.

Image: Firebird007/Shutterstcok