Despite NBCU’s resistance, the FCC has strong justification for differentiated ownership caps that strengthen competition and protect diverse local media.

In a world of cable, streaming, and satellites, it’s ironic that the policy world is in uproar over a $6 billion deal for Nexstar to buy Tegna, merging two large ownership groups for local broadcast television stations. That’s about the same as the breakup fee if Netflix’s acquisition of Warner Bros./Discovery doesn’t go through, but nevertheless, the Nexstar deal is drawing tremendous attention from Congress, interest groups, and competitors in the cable industry. Even President Donald Trump has weighed in on the broader issue of whether the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) should reform or repeal its rules on broadcast station ownership.

The Modern Media Ecosystem: Broadcast No Longer Stands Alone

The pushback reflects a deeper reality: our media ecosystem is not siloed like it once was. Broadcast television does not live in a separate world from cable or streaming—it has to compete for the eyeballs of viewers who can choose amongst a variety of devices and platforms. As Democratic FCC Commissioner Anna Gomez rightly observed recently, “even when you get your news on your phone as opposed to from a local broadcast, the source of that news is very often a local broadcast journalist that does the hard work, day in and day out.”

Those trends are only becoming more pronounced over time as our information environment evolves with our technology. These different platforms compete not only for viewer attention but also for the content viewers want. Sports leagues, for instance, can now play broadcast, streaming, and cable off one another to command top-dollar for program rights. And networks are in a particularly conflicted position as they decide where to allocate premium content between their broadcast affiliates, their cable channels, and their streaming platforms.

How These Technology Shifts Are Driving the FCC Ownership Fight

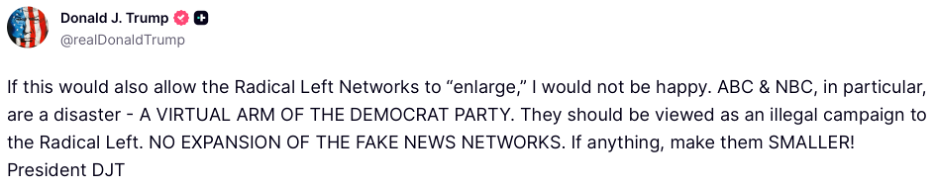

These underlying currents within the media landscape help drive the debate over broadcast ownership rules, which is turning into a fight between broadcast and cable. President Trump has been drawn into the middle of that fight, and he’s put down his marker. In the TruthSocial post heard round the media world, President Trump wrote of possible Federal Communications Commission action to reform or repeal the national ownership cap: “If this would allow the Radical Left Networks to ‘enlarge,’ I would not be happy. ABC & NBC, in particular, are a disaster . . . NO EXPANSION OF THE FAKE NEWS NETWORKS.”

Some news outlets read that post and reported that the President had rejected any change to the current cap. Other outlets reported that the post marked the start of a policy debate on reforming the rule. But there’s a third option—Trump’s post could well mark not the start but the end of the debate. FCC Chairman Brendan Carr can simply move forward with a rule that fits the President’s vision—repeal the national television ownership cap for independently owned stations while maintaining a cap on network-owned-and-operated stations.

The FCC’s Question: Should Network-Owned Stations Be Treated Differently?

The FCC’s Media Bureau floated this concept in its June 2025 invitation to refresh the record on the national television multiple ownership rule. In the Public Notice, the Media Bureau reminded readers that the FCC had previously rationalized the ownership cap as necessary to “preserve a balance in the marketplace between the networks and their local affiliates” by “placing limits on the expansion of network owned and operated station groups.” The Bureau asked if

these prior conclusions remain accurate in 2025, and can they be expected to remain valid going forward? If so, and the Commission retains a national audience reach cap, should common ownership of stations that are not affiliated with major national broadcast networks (i.e., ABC, CBS, NBC, or FOX) be excluded from the cap?

In other words, should the national ownership cap rule treat the network-owned and operated stations differently from independent stations when it came to the ownership cap?

In asking that question, the Bureau referenced a prior notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) which had similarly sought “comment on whether the national audience reach cap should apply equally to all ownership groups (e.g., groups that are network-owned or affiliated with cable networks versus those that are not).”

NBCU’s Arguments Against Changing the Ownership Cap

NBC Universal (NBCU) filed a comment in the record refresh, making three arguments in response: that such a distinction was incompatible with the FCC’s statutory authority to enact the national ownership cap, that such a distinction would be unconstitutional under the First Amendment, and that it would be bad policy.

NBCU is wrong on all three points. As Chairman Carr and the FCC consider the right public policy for the national television ownership rule moving forward, they should look at a rule that would differentiate between independent stations and network-owned stations.

First, NBCU reads the 2004 Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), which directed the FCC to modify the ownership rule to 39 percent, as a final act of congressional policymaking:

By reaffirming that the national ownership cap applies equally to all persons and entities, without regard to corporate ownership, Congress confirmed that the Commission lacks statutory authority to pick and choose only certain persons or entities for which the FCC could eliminate or modify the national ownership cap.

But Congress’s action in 2004 did not freeze the ownership rule in place until further congressional action. Congress told the FCC how to write a rule in a particular way, which reflects a policy choice to leave it to the FCC to rewrite the rule in the future if it wants. Congress could have enacted an actual statute that denied the FCC statutory authority to change the cap—it did not. NBCU is right—Congress said nothing in the 2004 CAA about independent versus network owners. But congressional inaction is not a bar to agency action, especially here when the agency has broad regulatory authority from Congress in its underlying substantive statute (the Communications Act).

NBCU next says that a differentiated cap would violate the US Constitution’s First Amendment, which precludes the government from “singl[ing] out ‘disfavored speakers’ for restrictions.” NBCU continues, “By offering relief to only certain entities and not others, based solely on the ownership composition of those entities and without any other legitimate justification, such disparate treatment would be unconstitutional.”

Why NBCU’s Legal Arguments Fall Short

This short-shrift analysis misses the mark in three ways. First, the US Supreme Court has recognized many times that the First Amendment applies differently in the broadcast television context than in normal speech settings: “[O]f all forms of communication, it is broadcasting that has received the most limited First Amendment protection.” So the normal import of free speech principles does not hold the same sway for broadcasters, a point NBCU skips over entirely.

Second, a rule exclusion for network-owned stations does not discriminate against disfavored speakers on illegitimate grounds. The government cannot regulate based on the content or viewpoint expressed in speech. A rule exclusion does neither. Shannon Bream’s Fox News Sunday and Bari Weiss’s CBS News are no more favored or disfavored than George Stephanopoulos’s ABC or Stephen Colbert’s CBS. No content or viewpoint is treated differently—the rule operates neutrally as to content and viewpoint. Different types of speakers are treated differently, but that happens all the time (just think of how different types of speakers are governed by different campaign finance rules).

Third, there is a “legitimate justification” for such a rule. NBCU asserts in its August 2025 comment that there is no policy justification for differential treatment. There are actually four separate policy reasons that the Commission could regulate network-owned stations differently from independent stations.

Policy Rationales for Treating Network-Owned Stations Differently

The balance of power between networks and affiliates is essential to a healthy broadcast ecosystem. In the 2017 NPRM, the Commission summarized findings from its 2002 Biennial Review Order, which recognized the need for policy that:

maintains the appropriate balance of power between broadcast networks and their local affiliate groups, in part by preventing the excessive accumulation of audience reach by network-owned groups, which are more likely to hold stations in multiple geographic markets with large populations.

The 2002 order reasoned that the FCC’s rules need to protect:

the leverage necessary for local affiliates to collectively negotiate to influence network programming decisions and to exercise their rights to preempt the airing of network programming in favor of programming the affiliates feel is better suited to local community needs.

A cap was necessary to “ensure that network-owned station groups could not achieve a level of direct audience reach that exceeds that of their local affiliates.”

The dissenting commissioners on the 2002 order agreed on the importance of this part of the policy: “[A] national cap is needed to serve the statutory goal of having independently owned affiliates continue to serve local community needs and to act as a counter-balance to the national networks.” (Statement of Comm’r Copps).

A sufficient number of local stations should remain free to serve their local communities and counteract the power of the networks. When a network acquires a local station, there is some risk that the network will seek to maximize revenue and national programming at the expense of local interests and needs. (Statement of Comm’r Adelstein).

The Commission is already focused on the significant imbalance in the network-affiliate relationship. Its recent inquiry into network-affiliate relations says:

Stakeholders representing the interests of affiliated or local television broadcasters have suggested that, in this time, an imbalance has developed in this relationship—that the horizontally and vertically integrated companies that now own national programming networks, cable companies, and streaming platforms can overpower affiliated broadcast television stations.

Having recognized this problem and having developed an extensive record documenting it, the Commission can appropriately enact policies that rebalance that power relationship to protect affiliates from further growth of network-owned stations.

Localism, Diversity, and Competition: Core Public-Interest Concerns

Separately, look at the three pillars of the public interest: localism, diversity, and competition. The Commission has previously recognized that network-owned stations do not best serve the interests of localism. Network-owned affiliates are less likely to preempt network programming in favor of alternative programming that’s of special interest or fit for their local market. This is common sense—an executive at a network-owned television station is going to be far more hesitant to preempt network programming than an executive at an independently owned television station, who is responsive primarily to his community’s public interest rather than bosses in New York or Los Angeles.

Commissioner Copps recognized this in the 2002 Biennial Order, writing: “record evidence demonstrates, among other things, that independently owned affiliates are better able to preempt network programming networks based on community standards and needs.” He reiterated later that he had

heard from broadcasters who had managed network-owned and operated stations and were unable to preempt programming that they believed was not suitable for their community. These broadcasters told us that programming decisions were often made by distant network executives rather than by local station managers. In contrast, we heard from independent local broadcasters who had stood up to programming they and their communities found inappropriate.

Not much has changed in the intervening 25 years—no ABC-owned stations stood up to ABC to say that Jimmy Kimmel’s program was not in the public interest—only independently owned affiliates had the wherewithal to stand up to the network.

Independently owned stations also better serve the Commission’s goal of viewpoint diversity. The networks are run by coastal liberal elites, and the news and entertainment programming they carry reflects those values. Independently owned stations, by contrast, are not beholden to the “programming decisions . . . made by distant network executives rather than by local station managers.” Local news programs run by independently owned stations not only provide local news, but they can also provide alternative viewpoints on national news from those carried on the networks. Local news programs on network-owned stations are less likely to do so.

In fact, further vertical integration of our nation’s information sources could negatively impact the viewpoint diversity that is core to the public interest. If networks are both vertically integrated in broadcast—owning both the national and local programming—while also being horizontally integrated across broadcast, cable, and streaming, that significantly reduces the overall viewpoint diversity across the media landscape broadly understood.

Finally, a rule on network-owned stations could be vital to ensuring competition within the media marketplace. Commissioner Copps sounded the alarm in 2003 to ensure “we do not end up with national vertically-integrated conglomerates that control the distribution channels and all of the content we see and hear.” More recently, media marketplace observers were struck by recent changes in Atlanta as CBS stripped Gray Media’s WANF of its network affiliation while launching WUPA as a network-owned station. This is a powerful, recent example of the leverage of the networks to use ownership changes to expand their reach at the expense of local station owners. The Commission could easily justify taking these tactics into account in formulating an ownership rule.

A Path Forward for 21st-Century Media Regulation

In summary, NBCU’s arguments in its comment all fall flat. There is extensive justification in both law and policy for a national ownership rule that treats network-owned stations differently from independently owned stations. The Commission could promulgate a revised rule that guarantees President Trump’s goal—no expansion for the networks—while at the same time providing greater freedom for ongoing ownership changes among the independently owned stations. Doing so will help broadcast television compete in the 21st century and promote the viewpoint diversity that is essential to a healthy media ecosystem.

About the Author: Daniel R. Suhr

Daniel R. Suhr is president of the Center for American Rights, a Chicago-based nonprofit law firm with an active practice before the FCC, and is a leading constitutional litigator. He previously was a managing attorney of a nonprofit law firm, was a senior advisor to Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, clerked for a federal judge, and worked for the Federalist Society. He has been featured in the media, including Fox News, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and others.

Image: Mark Van Scyoc/shutterstock