Russia’s oil trade survives through legal loopholes, shell companies, and intermediaries, not tankers alone— making courtrooms a more effective battlefield than risky escalation at sea.

The arrest of a senior executive, Adnan Ahmadszada, at Azerbaijan’s state energy giant underscores how far Moscow is willing to go to evade Western sanctions—and how vulnerable Europe’s energy markets remain. It also points to an alternative path for pressuring Russia’s illicit oil trade, one that may prove more effective than the emerging “tanker war” between Ukraine and Russia.

The war against Russia’s illicit oil trading will be won in the legal docket, not in the dockyards.

Sanctions Evasion in the Ahmadzada Case

The arrest follows accusations that Ahmadzada helped Russia evade sanctions imposed after its invasion of Ukraine. According to reporting, ships carrying Russian-origin oil were at times documented as Azerbaijani, Turkmen, or other non-sanctioned origins, enabling trade that may have skirted European Union (EU) embargoes. In some cases, Russian oil was allegedly mixed with non-sanctioned crude to facilitate its sale into European markets. For a Russia under wartime strain, every barrel matters.

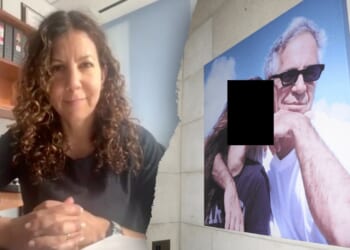

Not long ago, Adnan Ahmadzada was among the most influential figures in the global energy industry. He attended Formula 1 events and appeared in widely circulated photographs with Lionel Messi. He also held a number of senior positions at SOCAR, including executive director of SOCAR Trading and vice president for investments and marketing, before his alleged turn to criminality. Today, his downfall has become a matter of international consequence.

His arrest represents one of the largest anti-corruption actions ever undertaken by Azerbaijan’s security services. It is critical to Baku’s reputation—particularly that of its oil sector—as a reliable fossil-fuel producer seeking to position itself as an alternative supplier to Russia for Europe’s energy needs.

The case suggests Azerbaijan’s continued role as an important energy partner for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and its rapidly cooling relationship with Russia. The State Oil Company of the Republic of Azerbaijan (SOCAR) is one of the world’s most significant state-owned energy firms, with a substantial international footprint. It operates in more than twenty countries, employs over 66,000 people, is the largest foreign direct investor in Turkey, and plays an outsized role in Azerbaijan’s economy, which supports a population of just over ten million.

Escalation at Sea in the Ukraine War

Meanwhile, the war between Russia and Ukraine has increasingly extended to maritime energy infrastructure. Ukraine has launched a series of successful attacks on Russian-backed oil tankers in the Black Sea in late November and early December. Russia, for its part, has struck commercial shipping, including Turkish-owned vessels, at Ukraine’s Chornomorsk port.

By contrast, Ukraine’s maritime strikes carry significant risk. A major spill—on the scale of the Exxon Valdez—would be environmentally catastrophic and could hand Moscow a propaganda victory, undermining Kyiv’s strategic objectives. The 2024 Black Sea oil spill is also worth remembering in this regard. Ukraine is increasingly taking such risks. Last week, Ukrainian drones penetrated the Caspian Sea to destroy a Lukoil platform part of Russia’s largest oilfield.

These incidents generate dramatic headlines and compelling imagery. But a strong case can be made that the more effective way to curb Russia’s sanctions-busting is not through escalation at sea, but through sustained investigation of intermediaries like Ahmadzada who enable illicit trade. Malta was key to Ahmadzada’s efforts. Friendly companies stored the illicit oil, and from where it was re-exported, apparently with Maltese regulators turning a blind eye, according to EUReporter. Vessels linked to the scheme would ply Black Sea, Mediterranean and Persian Gulf routes. Sometimes ship-to-ship transfers of oil were involved and sometimes merely cargo relabelling.

The involvement of Malta in schemes such as this one suggests again how deep Russia’s illicit oil trading tentacles reach into Europe. Albania, a NATO member, has also been used for Russian oil smuggling. A major seizure involving a tanker with 22,500 tonnes of diesel occurred there in 2023. A similar seizure occurred in Albania this January.

The use of shell companies across multiple jurisdictions offered limited protection against exposure unless it relied essentially on the oil industry itself to turn a blind eye. This calls for further investigation and is perhaps more important to stopping Russia’s illicit trade than the fate of one powerful individual.

Russian Influence and the Logic of Exposure

There is also the possibility that Ahmadzada acted under pressure or influence from powerful Russian figures. He had to have known he would be caught. He appears to have been close to Vagit Alekperov, the founder of Lukoil and former Russian energy minister. Alekperov himself was forced to step down from Russia’s second-largest oil firm after being sanctioned by the United Kingdom and Australia.

Azerbaijani media is reporting Ahmadzada attended Alekperov’s birthday and had a $108 million superyacht, the garishly named Galatica Super Nova, registered in his own name.

The scale of the scheme itself is puzzling. Ahmadzada was already extremely wealthy. Oil-quality checks, combined with documentation reviews, significantly increase the risk of detection. Types of oil and indeed even oil from individual fields can have a unique chemical signature (natural gas is a different matter entirely). The scandal has impacted the price of Azerbaijani crude oil on the market. For Russia, this is a secondary goal to weaken the market strength of a country that has drifted out of its market, which may have been a secondary objective of the scheme.

Ahmadzada may yet face criminal charges not only in Azerbaijan, but also in the United Kingdom and Europe.

Why Courtrooms Matter More Than Burning Tankers

Images of executives answering uncomfortable questions in courtrooms may attract fewer clicks than burning tankers at sea, but they are ultimately more effective. The seizure of vessels, freezing of assets, and prosecution of intermediaries disrupt cartel-style logistics far more reliably than drone strikes alone.

Sanctions evasion depends on networks of bankers, insurers, traders, and port officials willing to look the other way. Exposing and prosecuting those networks raises costs and risks for Moscow at every stage of the process. In this contest, legal and financial warfare—backed by intelligence cooperation among NATO allies—offers Ukraine and the West a durable advantage that missiles alone cannot secure.

About the Author: Joseph Hammond

Joseph Hammond is a journalist and former Fulbright public policy fellow with the government of Malawi. He has reported from four continents on topics ranging from the Arab Spring to the M23 rebellion in the Eastern Congo, with bylines in Newsweek, The Washington Post, Forbes, and more. He has contributed to The National Interest since 2016. Hammond has been a recipient of fellowships organized by several think tanks, including the National Endowment for Democracy, the Atlantic Council of the United States, the Heinrich Boll Stiftung North America Foundation, and the Policy Center for the New South’s Atlantic Dialogue.

Image: Nina Alizada/shutterstock