In most wealthy nations, women have steadily closed the gap with men in education, income, and professional achievement. Today, they earn the majority of undergraduate and graduate degrees, including doctorates. More than half of all STEM degrees now go to women, and their presence in the tech industry has grown—from 31 percent in 2019 to 35 percent in 2023. In major metropolitan areas like Boston, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., women under 30 now match or outearn their male peers.

Given these gains, one might expect that as men and women converge in education and income, their cultural values and outlook on the world would also grow more aligned. Yet the opposite seems to be happening.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

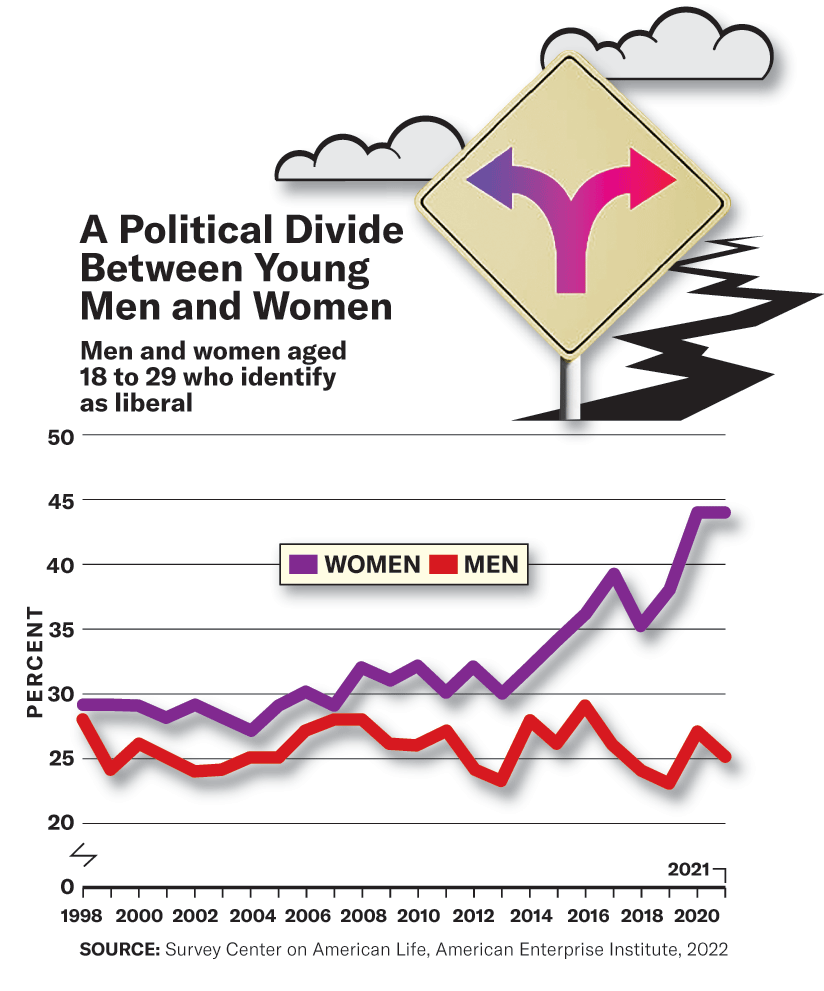

Nowhere is this divergence more striking than in politics. Since 2014, young women in the U.S. have grown increasingly left-leaning, while the political orientation of young men has remained relatively stable. By 2021, 44 percent of young women identified as liberal, compared with just 25 percent of young men—the largest gender gap in political affiliation recorded in 24 years of polling.

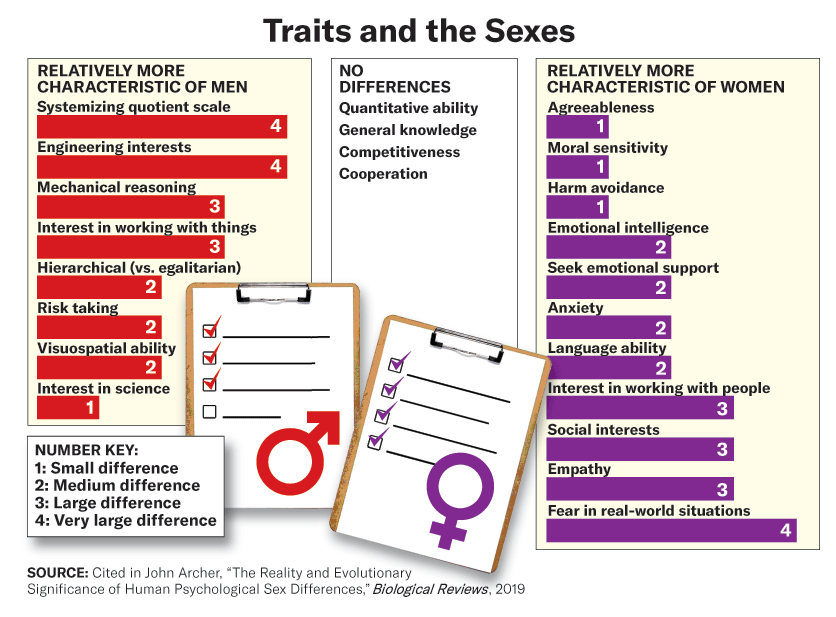

Why would men and women grow more politically divided even as they become more economically and educationally alike? The answer lies in persistent psychological and behavioral sex differences that continue to shape how each group sees the world.

Even in our supposedly enlightened times, “Is it a boy or a girl?” is still the first question asked of nearly every newborn—and the answer continues to shape how the child is raised. Research shows that from infancy, boys and girls are touched, comforted, spoken to, and treated differently by parents and caregivers. These early experiences may reinforce sex-typical patterns of behavior that often persist into adulthood.

People are intrinsically fascinated by psychological sex differences—the average differences between men and women in personality, behavior, and preferences. Psychologists have studied this topic systematically for decades, beginning with landmark works like The Psychology of Sex Differences (1974) by Eleanor Maccoby and Carol Jacklin. That book helped spark a wave of research that continues to this day. Since then, increasingly sophisticated methods have enabled researchers to detect subtle but consistent differences in how men and women think, feel, and act.

Men and women use language and think about the world in broadly similar ways. They experience the same basic emotions. Both seek kind, intelligent, and attractive romantic partners, enjoy sex, get jealous, make sacrifices for their children, compete for status, and sometimes resort to aggression in pursuit of their interests. In the end, women and men are more alike than different. But they are not identical.

To be sure, sociocultural influences play a role in creating those differences. But environmental factors don’t act on blank slates. To understand young men and young women, we must consider not only cultural context but also evolved sex differences. We are, after all, biological creatures. Like other mammals, we share similar physiology and emotional systems, so it’s not surprising that meaningful differences exist between human males and females.

To understand why psychological and behavioral sex differences evolved, the key concept is parental investment theory, developed by evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers in 1972. The basic idea is straightforward: the sex that invests more in offspring tends to be more selective when choosing a mate. This selectivity follows basic evolutionary logic: those with more to lose are more cautious and risk-averse. To put the stakes in perspective: raising a child from birth to independence in a traditional, preindustrial society requires an estimated 10 million to 13 million calories—the equivalent of about 20,000 Big Macs. For women, reproduction is enormously expensive.

Men also incur reproductive costs, though of a different kind. On average, they have about 20 percent more active metabolic tissue—such as muscle—that fuels their efforts in competition, courtship, and provisioning. While pregnancy requires a large, immediate investment from women, men’s reproductive effort is more gradual, spread out over a lifetime. In evolutionary terms, both sexes pay a price for reproduction, but in different currencies—women through gestation and caregiving, men through physical competition and resource acquisition.

Yet while nature can inform our understanding of human behavior, it does not dictate how we ought to live. A clearer grasp of sex differences can help guide our decisions. It cannot define our values.

Most people understand that physically, men and women are not the same. Prior to puberty, boys and girls are physically similar in size, strength, and skill—except when it comes to throwing. By the age of three, boys can throw objects farther, faster, and with greater accuracy than girls. No other physical activity in early childhood shows such a pronounced gap between the sexes. As they get older, boys across cultures refine this ability—tossing sticks, stones, balls, or whatever is at hand. By adolescence, their advantage in throwing ability has tripled. The male edge in throwing power and speed is evident even in the smallest hunter-gatherer societies.

During this period, boys also begin to outperform girls in a wide range of other physical skills, including sprinting and distance running, vertical and horizontal jumping, catching, sit-ups, balance, and grip strength. These differences are largely driven by puberty, which triggers dramatic increases in boys’ height, weight, and muscle mass. By this stage, the physical gap between the sexes is so pronounced that minimal overlap exists in these abilities.

Relatedly, human puberty leads to larger noses in boys to provide the oxygen they need to power their larger muscle mass. A typical teenage male will grow a nose about 10 percent bigger than that of a typical girl his size. Similarly, during pregnancy, women carrying male fetuses consume nearly 10 percent more calories than those carrying female ones.

It’s not just physical traits that differ. Men and women also show differences in areas like personality. Over the past few decades, the most widely supported framework among personality researchers has been the Five-Factor Model, which identifies five core traits.

Openness to Experience. People high in openness tend to be more creative and entrepreneurial, seek out new information and perspectives, and are more likely to get tattoos or piercings. They’re also more willing to relocate for school or work, compared with those who score low on this trait.

Conscientiousness. People who score high on this trait are industrious and tend to excel in school and at work. They are punctual, report greater job satisfaction, save more money, stick to exercise routines, and hold themselves to high standards.

Extroversion. Compared with introverts, extroverts enjoy social attention and are more likely to take on leadership roles. They tend to be more cooperative, have more friends and sex partners, and be more socially active. They also tend to drive faster and more recklessly—and get into more car accidents.

Agreeableness. Agreeable individuals tend to avoid conflict and prefer negotiation and compromise. They value harmonious social environments and want everyone to get along. They typically score high on measures of empathy and spend more time volunteering or helping others. They’re more likely to withdraw from confrontation and care deeply about being liked.

Emotional Stability. The hallmark of this trait is emotional steadiness: how much a person’s mood fluctuates. Those low in emotional stability (i.e., high in neuroticism) tend to react strongly to everyday setbacks and minor frustrations. Those higher in emotional stability are generally less prone to anxiety and depression and bounce back more easily from stress.

Each of these five broad personality traits includes a range of specific facets that capture the nuance and complexity of individual variations. For example, the global trait of conscientiousness includes six facets: competence, orderliness, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, and deliberation. Emotional stability encompasses facets such as anxiety, hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsivity, and vulnerability.

Men and women differ on some of the Big Five personality traits, with the most pronounced differences found in agreeableness and emotional stability. Women consistently score higher than men on agreeableness. Two key facets of this trait—trust and tender-mindedness—help explain the gap. Trust reflects a tendency to cooperate with others and give them the benefit of the doubt. Tender-mindedness involves empathy and sympathy, particularly toward the disadvantaged. Women score significantly higher than men on both. This may help explain why women tend to be more politically progressive than men. Agreeableness correlates with political orientation: the higher someone scores on this trait, the more likely the person is to identify as a liberal.

There is also a notable sex difference in emotional stability, with women scoring moderately lower than men. The anxiety facet shows the largest sex gap across cultures, with women consistently scoring higher. Other measures indicate that women also score higher on fearfulness and feelings of vulnerability. Interestingly, a 2021 study found that physical strength significantly reduces the sex differences in anxiety and fearfulness—suggesting that elevated levels of these traits may be adaptive for individuals who are less physically formidable. The researchers propose that “some sex-based variation in personality may be partly attributable to variation in physical attributes.” Low emotional stability is associated with a greater likelihood of holding liberal political views, perhaps helping to explain some of the observed political differences between men and women.

Adult men and women differ both in the incidence of depression and in the nature of their depressive symptoms—but these differences don’t appear in childhood. Before puberty, rates of depression are similar across sexes. After puberty, however, women experience depression at roughly twice the rate of men—a finding replicated in 25 European countries. About 25 percent of women will experience at least one depressive episode in their lifetime, compared with just 10 percent of men.

Low levels of emotional stability can sometimes be useful. As Tyler Cowen and Daniel Gross suggest in their book on talent spotting, “If you are looking to hire a crusader on behalf of a social justice cause, someone who will notice injustices and then complain about them, neuroticism might be a desirable trait.”

Mental health does appear to influence political ideology more than the reverse. Researcher Zach Goldberg has shown that rising levels of psychological distress predict later increases in liberal attitudes among girls and among liberals of both sexes, as well as a rise in liberal self-identification. In a series of studies, Vicki Helgeson and Heidi Fritz explored sex differences in what they call “unmitigated communion”—defined as “an excessive concern with others and placing others’ needs before one’s own.” To measure it, they developed a simple scale where participants rated their agreement with statements such as “For me to be happy, I need others to be happy” and “I often worry about others’ problems.” Women consistently score higher than men. This may help explain why modern political activism is often so feminine in style—what Kay Hymowitz has described as “the new girl disorder,” rooted in concern for others.

Interestingly, countries with greater sociopolitical equality and gender egalitarianism tend to show the largest sex differences in personality traits. For example, men and women in highly egalitarian countries like Denmark and Sweden differ more from each other than do men and women in more traditional societies such as Vietnam and Botswana.

This association between sociopolitical equality and larger sex differences holds for the Big Five personality traits and for other behaviors as well. Take crying: women across cultures cry more than men, but the gap is especially pronounced in rich countries with high levels of sociopolitical equality.

The same pattern appears in educational preferences. In developing countries, women are more likely to study engineering and other lucrative fields. In richer countries, where economic security is more assured, women tend to opt for less remunerative majors such as communications or psychology.

In relatively rich and free societies, people are better able to express their underlying traits and preferences. In contrast, less affluent and less egalitarian societies tend to impose stricter behavioral expectations, which compress sex differences. Psychologist Steve Stewart-Williams has summed up this dynamic succinctly: “Treating men and women the same makes them different, and treating them differently makes them the same.”

Even sex differences in height, BMI, obesity, and blood pressure are larger in countries with more egalitarian sex-role socialization. Across societies, men tend to be taller and heavier and to have higher blood pressure than women—but these differences are especially large in wealthier nations. In materially scarce environments, men’s physical development is more constrained relative to women’s. Put simply, men have greater physical capacity for growth and change, and material abundance—particularly adequate food and nutrition—allows those underlying traits to emerge more fully.

Many in Western societies assume that treating men and women the same will naturally lead to convergence in their interests and preferences. But the world doesn’t work that way. The freer people are and the more fairly they’re treated, the more their differences tend to emerge rather than disappear. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that young men and women are diverging politically more than previous generations did.

A baby boy born in the U.S. faces an astonishing risk profile. Men are three times more likely to die before age 25, three times more likely to become addicted to drugs or alcohol, and 19 times more likely to end up in jail.

A man is more than twice as likely as a woman to be in a car accident—and three times as likely to be involved in two. Even as pedestrians, men take more risks: twice as many men as women are killed while simply crossing the street. Maleness is by far the strongest risk factor for violence. Men kill other men at a rate 26 times higher than women kill women.

Oxford evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar has observed that when two women converse, they usually face each other directly. The same is true when a woman and a man are speaking. But when two men are engaged in friendly conversation, they almost always stand at an angle—about 120 degrees—nearly side by side. This is because, traditionally, the only time men stare directly at each other is when they’re about to engage in verbal or physical conflict.

Men have a higher tolerance for pain. In experimental studies using identical pain-inducing stimuli, women consistently responded more quickly to bodily injury and endured it for less time than men. This difference diminished with age but never disappeared.

An evolutionary model offers an explanation. Because the reproductive ceiling is much higher for males than it is for females, the variance in reproductive success differs significantly between the sexes. In fact, 8,000 years ago, 17 women reproduced for every one man. As a rule, the greater the variance in reproduction, the more ferocious the competition within the sex showing the higher variance. Throughout evolutionary history, men have engaged in high-risk competition for the status and resources that boost their attractiveness to potential mates. With greater aggression comes higher likelihood of injury and death—one reason that men are more often the victims of violence than women.

Homicide is a crime committed overwhelmingly by young men. While material conditions and ideological factors can amplify or restrain violent behavior, the evolutionary roots of this impulse predate humanity itself. Globally, men commit more than 90 percent of homicides. As noted earlier, most victims are also male—about 70 percent. Interestingly, the same pattern holds for chimpanzees: 92 percent of chimpanzee killers and 73 percent of their victims are male.

Violent death rates among hunter-gatherer societies with little or no contact with Western culture exceed those of even the most crime-ridden cities in contemporary America. In these societies, roughly one in seven men dies because of homicide. A global assessment of 31 hunter-gatherer groups found that 64 percent engaged in warfare once every two years—conflicts carried out almost exclusively by men.

In a 2012 paper published in Human Nature, the authors observed that “if modern Western societies had homicide rates as high as some foraging peoples, a male graduate student would be more likely to be killed than to get a tenure-track position.” Many have noted that women seem overrepresented in disruptive campus protests—but elite colleges often select individuals who do not conform to traditional gender norms. In the real world, antisocial behavior like vandalism and violence remains overwhelmingly male.

Unsurprisingly, wealth has a clearer impact on reproductive success for men than for women. Wealthy men tend to have more children than poor men, while the fertility gap between rich and poor women is much smaller. This is partly because a woman’s reproductive potential doesn’t depend on how many partners she can attract. A man with 20 wives can father 20 children at once; a woman with 20 husbands cannot. This basic asymmetry helps account for some of the persistent differences in male and female sexual preferences.

A 2016 study of 33 nonindustrialized, small-scale societies found that men’s status—measured by wealth and political influence—is positively associated with several reproductively relevant outcomes, including number of sex partners, number of offspring, and number of offspring surviving into adulthood.

In modern societies, the same pattern holds. Men who attain high income or occupational prestige are significantly more likely to find a long-term partner and have children. A 2019 study found that men at the top of the earnings distribution have more than a 90 percent chance of securing a committed romantic partner; for men at the bottom, that figure falls below 40 percent. In most societies, successful men attempt to convert their status into reproductive success.

On average, men’s self-esteem is more closely tied to salary, social status, and wealth—and these factors also shape their desirability as romantic partners, according to studies of female mate preferences. This helps explain why men are more likely to work long hours, relocate for jobs, and sacrifice their health in pursuit of career advancement. Women with high incomes, postgraduate degrees, and prestigious professions tend to place even greater value on wealth and status in a husband than other women do.

Even in the most egalitarian countries, men tend to prefer more sex partners than women do. In Norway, researchers asked how many sex partners people would like over the next 30 years. On average, women preferred five; men preferred 25. Despite what glossy magazines might suggest, it is men who are the most enthusiastic about polyamory. They are twice as likely as women to have participated in a polyamorous relationship and three times as likely to want one. Men are also far more supportive of non-monogamy, open relationships, friends with benefits, throuples, and swinging.

Many objections to research on sex differences stem from a sentimental belief that nature ought to support progressive political ideals. Consider sexual behavior: progressives often assume that casual sex is both natural and healthy. So when studies show that men are more inclined toward it and enjoy it more than women, many take this as a moral affront, as if it implies that men are liberated while women are repressed.

This discomfort has given rise to new categories like “demisexual”—a term used mostly by young women who experience sexual attraction only after forming an emotional bond. In essence, it reframes a traditional romantic norm. But in a culture where emotional commitment and monogamy are often dismissed or pathologized, some young women feel compelled to invent a new sexual orientation simply to legitimize their natural preference for commitment.

Due to these sex differences, all else being equal, mothers and fathers have historically been more motivated to pass their wealth to their sons than to their daughters. Rich sons had the potential to father far more children than rich daughters could bear. In part, this reproductive logic helped fuel the global spread of gender inequality.

Over the past few decades, researchers have quietly uncovered a consistent, if uncomfortable, pattern: boys are more fragile than they seem. Compared with girls, they are more sensitive to instability, more affected by parenting quality, and more likely to struggle when structure breaks down. These vulnerabilities may not be obvious early on, but by adolescence and adulthood, the effects compound. In schools, job markets, and relationships, more young men are falling behind—not because they lack potential but because they depend more on environmental support that is increasingly absent.

Interestingly, while childhood instability is linked with riskier and more harmful behaviors in adulthood, childhood poverty is not. A 2016 study led by psychologist Jenalee Doom at the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Child Development revealed that rich kids from unstable homes are far likelier to abuse drugs than poor kids from stable homes. Instability also appears to affect boys more than girls. Psychologist Peter K. Jonason and his colleagues found that among men—but not women—childhood instability was associated with higher scores on the Dark Triad: aggression, impulsivity, and disregard for others. Childhood socioeconomic status had no effect on these traits.

The effects of instability are especially striking when viewed through the lens of gender. In a 2016 study, Harvard economist Raj Chetty examined boys and girls born between 1980 and 1982 in the same disadvantaged neighborhoods. By age 30, the women had achieved better economic and educational outcomes than the men. This gender gap in college attendance exists across all income levels but is widest among the poor. Among affluent families, girls are only slightly more likely than boys to attend college. Among low-income families, girls are far more likely to do so.

The pattern reverses in intact families. Among children raised by poor, married parents, boys are slightly less likely than girls to grow up unemployed. In other words, single parenthood appears especially detrimental for boys, while married-parent households offer them a particular advantage.

These findings align with research by University of Chicago economist Marianne Bertrand, who found that while all children suffer in broken families, boys suffer more. Her study showed that boys raised by single parents are twice as likely to be suspended for disruptive behavior as girls in the same circumstances—and that this gender gap narrows significantly in intact families. “All other family structures appear detrimental to boys,” the study notes.

It may be for this reason—the sex difference in responsiveness to environmental inputs—that most cultures throughout history have established rites of passage for boys. As psychologist Roy Baumeister observes, “in many societies, any girl who grows up automatically becomes a woman. . . . Meanwhile, a boy does not automatically become a man, and instead is often required to prove himself, usually by passing stringent tests or producing more than he consumes.”

Anthropologist David Gilmore found similar examples across dozens of cultures. In Manhood in the Making, he argues that masculinity is not a biological given but a cultural achievement—one imposed on boys through testing, instruction, and often hardship. Left unguided, boys tend toward apathy, self-indulgence, and an aversion to responsibility. Contrary to the belief that males are naturally ambitious and risk-seeking, Gilmore shows that societies have long used rituals and norms to cultivate these traits in young men.

Unlike femininity, which is grounded in biological milestones such as menstruation or childbirth, masculinity has always required external validation. A girl becomes a woman through processes largely beyond her control. A boy, by contrast, must prove he is a man—through work, risk, sacrifice, and service. In traditional societies, this meant demonstrating value to the group. Today, however, the scaffolding that once guided boys into manhood has eroded. The expectations once placed on young men—to work hard, support others, and pursue self-mastery—have largely disappeared. As a result, many are adrift.

Ironically, the belief that males are innately power-hungry and in need of restraint has obscured a deeper truth: boys aren’t overzealous; they’re undermotivated. The real challenge isn’t curbing male ambition but igniting it. Across cultures and centuries, societies understood that, left unguided, boys don’t become dangerous; they become disengaged. Today, we’ve dismantled the norms that once shaped boys into men, removed the ladder, and then blamed them for not climbing it. If we want fewer young men retreating from school, work, and family life, we need to stop pathologizing masculinity—and start rebuilding the cultural pathways that once helped boys grow into responsible men.

Despite growing equality in education and the workplace, men and women remain shaped by deep-seated biological and psychological differences that influence their values, behaviors, and politics. Paradoxically, in affluent and egalitarian societies, these differences become more pronounced, not diminished. Acknowledging these realities means designing institutions, norms, and policies that better reflect how men and women respond differently to freedom, adversity, and opportunity. If we hope to bridge current divides and build a more cohesive society, we must stop pretending that the sexes are interchangeable and instead draw strength from their differences.

Top Photo: By 2021, 44 percent of young women identified as liberal . . . (Alyssa Schukar/The New York Times/Redux)

Source link