The images of the great martyrs of the past, those disciples and followers of Christ who committed their all—body and soul—to the Great Commission, to spread the Word to all worldwide, inspired Jean de Brébeuf as a young man growing up in France. With the intent to sacrifice himself for Christ, he became a novice of the Jesuit order in Rouen, and in 1623 he was ordained a Jesuit priest. Two years later, when he was thirty-two-years old, he journeyed to America.

Since Champlain’s founding of New France, the French had generally befriended the native tribes of the St. Lawrence Valley. These were largely Algonquin tribes of the American northeast. French missionaries, the Jesuits and Franciscans, were pushing further west during the seventeenth century into a region the French called Huronia—what is today west of Lake Ontario and north of Lake Erie—where an Iroquoian tribe, the Hurons, resided. This region among the Hurons was where Père Brébeuf ultimately wanted to perform his missionary work.

Upon arriving in New France, he at first served as a missionary with an Algonquin tribe, the Montagnais (today called the Innu), learning their language and culture so he could teach them about the life of Jesus, the sacraments, prayers, and the Scriptures.

Between 1629 and 1632, Père Brébeuf and other missionaries had to return to France because the English had taken control of Quebec; but in 1632 England relinquished control, and the missionaries returned.

Brébeuf journeyed to Huronia. Foretelling his future fate, Brébeuf had proclaimed on the eve of his return to New France:

Lord Jesus, my Redeemer, Thou hast saved me with Thy Blood and precious Death. In return for this favor, I promise to serve Thee all my life in Thy Society of Jesus, and never to serve anyone but Thee. I sign this promise with my own blood, ready to sacrifice it all as willingly as I do this drop.

He ministered to the Neutral Indians of the Niagara region (an Iroquoian tribe) as well as the Huron (now known as the Wendat) during the 1630s and early 1640s. Eventually, Brébeuf and other missionaries worked out of Fort St. Marie on the Wye River.

The Hurons were much weaker than the Iroquois tribes to the south, the Mohawks and Senecas, and thus were under constant threat of attack. The fort provided some protection—though not enough, for the Jesuits had spread themselves out in ten different missions in the Huron region.

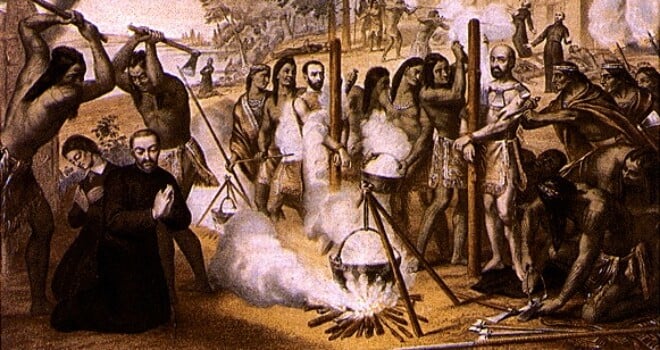

In 1649, Seneca and Mohawk warriors attacked Huron villages, overrunning them. Père Brébeuf and a colleague, Père Gabriel Lalemant, where captured. The Huron villagers and the French who lived and served the missionaries were either killed or captured.

The Iroquois peoples of this time, before their conversion to Christianity, believed in torturing their victims to taunt and humiliate them, to watch them suffer, and to avenge their dead. The Black Robes such as Brébeuf and Lalemant especially annoyed the Iroquois because the Jesuits had made known their desire to come among the Iroquois to teach and convert them, to “turn them to French ways of Christian civilization.”

So the warriors made a point with these two Jesuits: they stripped them, pulled out their fingernails, and beat them with cudgels. All the while, Père Brébeuf prayed and sang; he told the other Christians suffering torment to be true to Christ who suffered with them.

Some of Brébeuf ‘s tormentors knew him. One, whom Brébeuf had tried to convert several years before, said to the priest, according to an eyewitness whose memories were later recorded in the Jesuit Relations: “thou sayest that Baptism and the sufferings of this life lead straight to Paradise; thou wilt go soon, for I am going to baptize thee, and to make thee suffer well, in order to go the sooner to thy Paradise.”

The “baptizer,” true to his words, began the most unimaginable tortures that are better left unsaid. It took Brébeuf hours to die and Lalemant even longer. Their martyrdom was truly Christ-like—the intense pain, the need for patience, waiting upon God’s will to take them to Him.

Brébeuf knew that he was not the first, that there had been thousands of Catholic martyrs over the centuries. In New France, there had been martyrs before him, and others would come after. French Jesuit René Goupil, for example, had suffered martyrdom in 1642, seven years earlier, at the hands of the Iroquois.

Another French martyr, Isaac Jogues, had escaped with his life after watching Goupil’s martyrdom. “During thirteen days,” he recalled, “that we spent on that journey, I suffered in the body torments almost unendurable, and, in the soul, mortal anguish.” Jogues returned to France in 1646 only to come again among the Huron, was captured again, and tortured again, this time to death. He had been sent as a peace ambassador to the Mohawks, who met him and his fellow Jesuit Jean de Lalande with death.

Another who had been martyred, just a year before Père Brébeuf, was Jesuit Antoine Daniel, who during an attack on the Huron village of St. Joseph, regardless of his own danger, baptized as many children as he could before they were clubbed to death by the invaders. When all was lost, he stood between the attackers and the innocent children and aged and was struck down by the aggressors.

There were two other Jesuits who died the same year as Père Brébeuf: Charles Garnier and Noël Chabanel. These eight who died during the decade of the 1640s were canonized by Pope Pius XI in 1930 and are known collectively as the Canadian martyrs.

The word martyr in the New Testament is Greek for witness. The Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, and other Catholic missionaries who came to America knew that in going among the Native Americans that some tribes like the Iroquois were intransigent toward their teachings, and their violence and cruelty knew no bounds. Père Brébeuf knew this, yet such was his drive, his desire to spread the word of God and to fulfill the Great Commission, that he put his life in God’s hands, knowing that whatever his fate it would conform to Divine Providence. Even if he was to be tortured to a horrible, bloody death, he believed that it was God’s will that the other sufferers watch and learn, and that even the torturers watch and learn, so that in time, eventually, they too would surrender to the loving, merciful embrace of our God.

Image from Wikimedia Commons