Something I did not have on my bingo card for 2025 was a renewed interest in the ideas of Karl Marx. To some degree, Marx has always had his partisans in the United States, where a vocal segment of the political left has been promoting Marxism for decades. This year, however, we saw discussion about Marx emerge beyond the far left to become part of mainstream discourse. This was prompted, in part, by the surprisingly meteoric rise of Zohran Mamdani, the openly socialist Mayor-Elect of New York City. In a broader sense, though, this renewed interest in Marx is part of the political realignment we are witnessing in the U.S. as the post-war political order continues to break down. In light of this, Americans are increasingly considering alternative political ideas considered on the fringe a mere generation ago.

A renewed interest in Marx may be surprising, given the appallingly bloody history of Marxism in practice. It seems that no amount of failure, no amount of bloodshed, no level of economic stagnation nor degree of human misery is ever sufficient to fully expel the Marxist demon. It ebbs and flows, sometimes lingering on the outskirts of civil discourse, sometimes reentering the social arena when the time seems opportune.

And yet, Marx’s message would not resonate so deeply if it were wholly false. Karl Marx’s vision of humanity was tragically flawed in many respects, but it would not have proved so compelling if it did not get a few things right.

One of Marx’s most compelling arguments concerns the problem of modern work. Marx argued that the industrialization of society under capitalism has resulted in the alienation of the worker. For Marx, alienation refers to the separation of workers from the products they create. Because they don’t control production, their labor is external, forced, and unfulfilling. This loss of control makes workers feel powerless and disconnected from themselves and society. This dehumanization turns workers into just another commodity. “These laborers,” says Marx in the Communist Manifesto, “who must sell themselves piecemeal, are a commodity, like every other article of commerce, and are consequently exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition, to all the fluctuations of the market.”

Most of us who have been in the workplace for any length of time have experienced this alienation firsthand—we often feel disconnected from our work, commodified, and entirely replaceable. This problem has been noted by Catholic thinkers such as G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, as well as taught by Leo XIII and John Paul II. John Paul II in particular observed that the alienation of the worker transforms meaningful human labor into meaningless drudgery—what John Paul II called “toil” in his labor encyclical Laborem Exercens.

One of the worst aspects of the modern economy is its dehumanization, the way it transformed the craftsmen of yesteryear into today’s wage slave, alienating the worker from everything that makes human labor meaningful and empowering, a fact recognized by minds as diverse as Marx, Chesterton, and John Paul II. Marx thus recognizes that man is supposed to find a certain ennobling dignity in his work that the industrial society has robbed him of.

Marx also correctly observed that rulers have a tendency to stoke nationalist or ethnic rivalries as a means of externalizing the anger of their peoples against a foreign adversary to distract them from domestic problems. To some degree, this is simply an observation about human nature and the dynamics of power—people are easily distracted, and framing an outside power as an existential threat is a time-tested tactic leaders use to unite their people behind them while projecting their frustrations onto an external opponent. Marx was keenly aware of how traditional nationalist and ethnic rivalries can be harnessed by unscrupulous politicians for political gain. In this, Marx shows himself not only understanding of the nature of power, but insightful about the psychology of mass manipulation.

One of Marx’s most poignant criticisms of modernity was his warning about the danger of concentrating capital in the hands of a few elites. The system of capitalism is so-called because the means of production (capital) tends to concentrate in the hands of a small oligarchy of elites (capitalists). When capital is concentrated in the hands of a few, the industrial production of the nation is directed not towards the public good but towards private gain, at the expense of the workers who make this gain possible. Marx observed that the concentration of labor in too few hands had resulted in tremendous social evils, such as:

“…overproduction and crises…the inevitable ruin of the petty bourgeois [lower middle class] and peasant, the misery of the proletariat [working class], the anarchy in production, the crying inequalities in the distribution of wealth, the industrial war of extermination between nations, the dissolution of old moral bonds, of the old family relations, of the old nationalities.” (Communist Manifesto)

This hyper-concentration of wealth has been decried by every notable Catholic thinker who has commented on modern labor. Pope Leo XIII, for example, observed that “the hiring of labor and the conduct of trade are concentrated in the hands of comparatively few; so that a small number of very rich men have been able to lay upon the teeming masses of the laboring poor a yoke little better than that of slavery itself” (Rerum Novarum, 3).

Ultimately, Marx was far more successful at diagnosing the evils of modernity than remedying them. To use an aphorism of Chesterton, Marx was right about what was wrong, but wrong about what was right.

For example, Marx’s solution to the problem of worker alienation is the abolition of private property. Marx contends that it is private property which turns labor into a commodity and separates workers from control over their work and its fruits. It is important to note that by abolition of private property, Marx does not mean personal possessions; rather, he means private property in productive forces, like factories and land. Marx believed that collective ownership of these assets would allow workers to control their labor, reunite with its products, and engage in free, creative activity that affirms their humanity. It’s also important to note, however, that in Marxism, ownership by “the workers” is a euphemism for ownership by the state. The Communist state is said to be “the workers” because it represents the interest of the workers. Communism thus proposes to redress the problem of worker alienation by creating a Leviathan government that exercises totalitarian control over production.

This is precisely the opposite remedy from what Catholic social teaching proscribes. Catholic social teaching calls not for a reduction but a broadening of authentic private property—ownership by regular people. Catholic examples of this are workers cooperatives, whereby businesses are truly owned by the workers themselves who have a direct say in the management of the business and reap a proportional share in its success. It is precisely the access to private property that guards the human dignity Marx was so concerned about.

This also ties into the Catholic remedy for the hyper-concentration of wealth Marx rightly critiqued. Marx claims to dislike the concentration of capital, but when we examine his system, we see that Marx’s objection is not so much against this concentration itself, but rather in whose hands it is concentrated. Marx’s scheme would simply exchange one concentration for another—concentration in the hands of Big Business for concentration in the hands of Big Government.

The Catechism, however, speaks of a “right to private property” that is “legitimate for guaranteeing the freedom and dignity of persons and for helping each of them to meet his basic needs and the needs of those in his charge” (CCC 2402-2403). While the right to private property is not unlimited, it is nevertheless a true and proper right, the elimination of which can only be detrimental to human flourishing, no matter how noble the intention.

Contra Marx, Catholic social teaching persuasively argues that what is needed is not a reconcentration of property in government hands, but a broader distribution of property in a multitude of private hands. This idea can be found in the works of Leo XIII, Pius XI, John Paul II, Chesterton, Belloc, and others. The ideal situation is not the state holding all property as a trustee for the people, but the people themselves holding productive property—a society of small owners.

Finally, while Marx was right that ethnicity and nationalism can be co-opted by corrupt politicians for nefarious purposes, things like ethnicity, nationality, and culture are nevertheless integral to a people’s sense of self-identity. While Marx did not deny the importance of culture, he viewed it as ancillary to the economic realities he believed underlay all human activity. For Marx, the economy was the base, the foundation of civilization; everything else—culture, religion, ethnicity, and so forth—were “superstructures,” secondary ideas built from and dependent upon the economy. This reflects Marx’s materialism, the belief that matter is ultimately all that exists and all that truly matters. But whereas the Marxian world is materialistic, the Catholic world is metaphysical—man does not live by bread alone; we are ordered towards truth, goodness, and beauty, which are found in God. Marx’s view of humanity is tragically thin, fundamentally underestimating the transcendent orientation of mankind.

This brief article has barely skimmed the surface of the subject, but thankfully there are other Catholics today addressing the challenged posed by Marx if you want to dig in deeper. Of note is Robert Orlando’s new book Karl Marx: The Divine Tragedy (TAN Books, 2025). Orlando’s book considers Marx not merely as a socio-economic revolutionary, but as a dark prophet, evaluating his thought through the lens of the structures of sin from Dante’s Divine Comedy. If you’d like something shorter that can be listened to, Brandon Vogt has an episode dedicated to Marx on his Dead Men Talking YouTube series. I also have a few resources you can check out as well: first, a lengthy article entitled “Communism Explained: Principles, History, and Catholic Insights” on the Homeschool Connections blog; and second, a little booklet called A Catechism of Communism for Catholic High School Students (this latter was written by a Passionist priest in the 1930s, but I have reprinted it with an original introduction expanding on the author’s work).

As the echoes of Marx’s critiques resurface amid our era’s discontent, Catholics are called not merely to refute his errors but to boldly reclaim and enact the Church’s vision of a just society—one where widespread ownership restores human dignity to labor, where the transcendent purpose of work draws us toward God rather than reducing us to cogs in a material machine, and where true solidarity among peoples flourishes without the false promises of collectivism or the excesses of unchecked capital, offering the world a lived alternative that alone can heal the wounds of modernity.

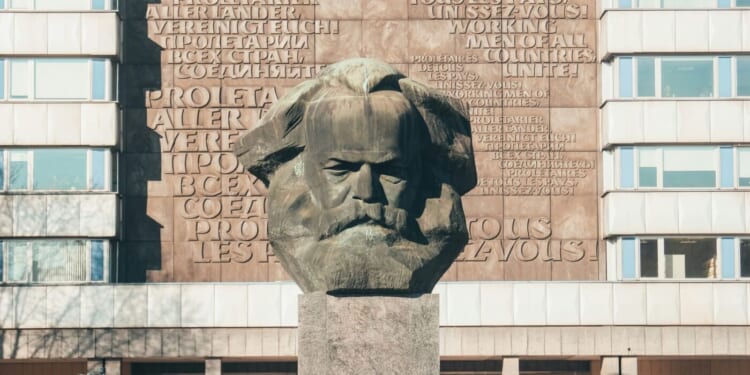

Photo by Maximilian Scheffler on Unsplash