Recent stories of note:

“The healing powers of Hogarth”

Kirsten Tambling, Apollo

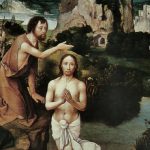

William Hogarth is not the first name one associates with the grand manner, and yet the recent restoration of St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London provides clear evidence of Hogarth’s capabilities when it came to history painting, as Kirsten Tambling reports. The medieval hospital, thanks to a comprehensive redesign in the 1730s, features two monumental religious works by the artist, Christ at the Pool of Bethesda and The Good Samaritan. Fittingly for the location, miraculous cures are the subject of both paintings: the former shows Christ surrounded by a group of diseased figures who are about to be healed, while the latter depicts the proverbial Samaritan tending to the wounds of a shocked, nude youth. While the classical nude poses and the ancient ruins in the background are familiar features of the contemporaneous grand style, there are some elements that remind us of the Hogarth we know and love, such as a boldly painted mastiff licking its wounds in the foreground of The Good Samaritan.

“What Should a National Museum Be?”

Edward Rothstein, The Wall Street Journal

The Trump administration’s attempts to reform the Smithsonian have generated many headlines, but less attention has been paid to the origins of our current museological discontents. In his review of Smithson’s Gamble: The Smithsonian Institution in American Life, 1836–1906 by Tom D. Crouch, Edward Rothstein goes over the rise and recent decline of this most American of institutions. In Crouch’s book, it emerges that James Smithson, who in 1829 bequeathed the United States the extraordinary sum of five hundred thousand dollars to found “an Establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men,” had never even visited the New World but believed in the unique potential of the fledgling nation to advance science. Rothstein then dwells on how the curators of the Smithsonian began to deviate from this noble vision, largely to overcorrect for the institution’s earlier unsavory practice of collecting tens of thousands of human bones, especially those of Native Americans. While the darker chapters of American history should not be ignored, the current problem of the Smithsonian, as Rothstein correctly diagnoses, “is not that injustices are examined, but that so little else is.”

“Darkness & Light”

Ritchie Robertson, Literary Review

Few figures are as easy to romanticize as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Upon meeting him in 1808, Napoleon remarked, “Vous êtes un homme” (You are a man), a high compliment coming from one of the most distinguished specimens of that species. In his review of Matthew Bell’s biography of the literary and scientific giant, Ritchie Robertson presents some of the less well-known aspects of Goethe’s life and thought. It had never occurred to me, for instance, that Goethe’s love of nature, which proved to be so influential on the budding Romantic movement, ultimately stemmed directly from one of his biggest influences: Spinoza, with his slogan deus sive natura. Like Spinoza, Goethe was a noted natural philosopher: his longest book, the Theory of Colors (1810), was a refutation of Newton’s theories on the color spectrum and anticipated modern color theory, and his work on botany and biology was an important influence on Darwin. Ironically, the archetypal Romantic emerges as one of the last great representatives of the Age of Reason, when the arts and sciences were still happily married.