USS Edsall: The US Navy’s “Dancing Mouse” Drove the Japanese Nuts

The USS Edsall—or the “dancing mouse,” as her brutal Japanese opponents dubbed her—exemplified the very best that the US Navy has to offer.

The Second World War is often remembered for its epic size and scope. Indeed, the way the world recalls World War II today sounds much like the way that ancient people remembered the Peloponnesian War: a grand, dark, gruesome affair, but one full of swashbuckling adventure, swaggering soldiers, and incredible military innovations.

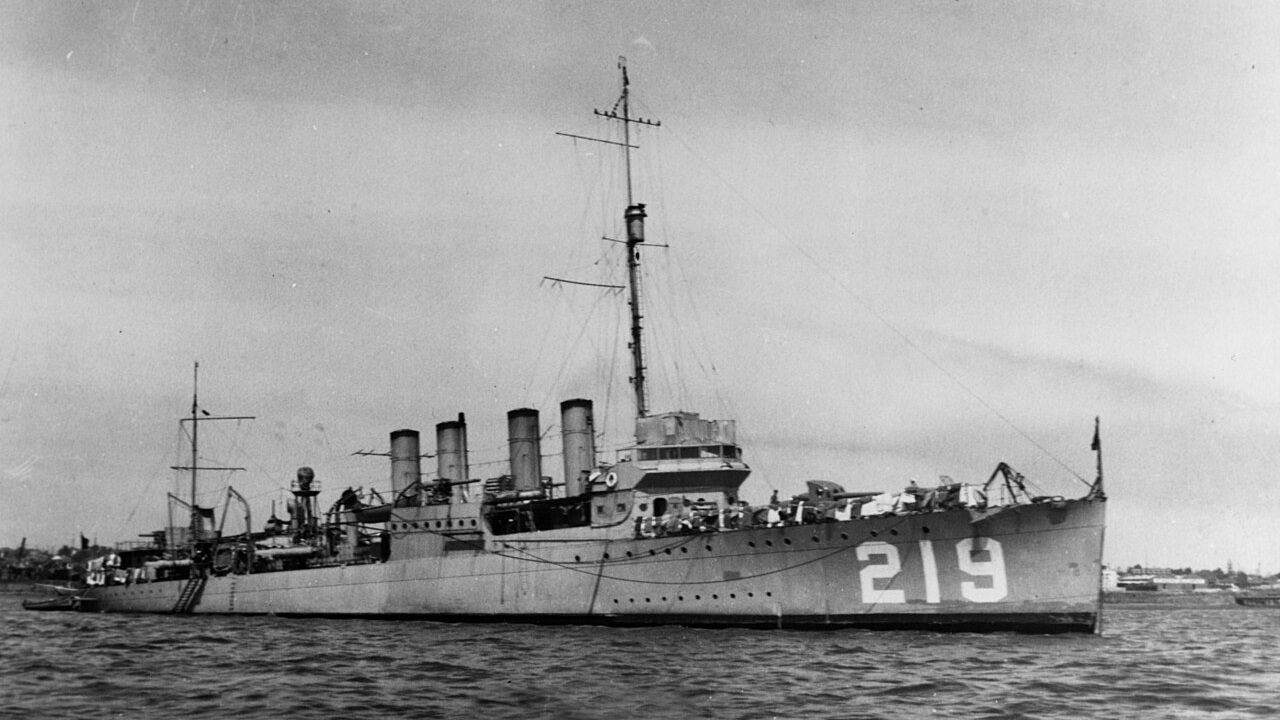

Whenever men and their war machines meet the crucible of epic battle, there are always instances of heroism and tragedy. The USS Edsall (DD-219), a United States Navy Clemson-class “flush deck” (or “four-piper”) destroyer, is one such platform that met a fiery end—but went down in a memorable way.

In mid-2023, after having been missing since the fateful evening hours of March 1, 1942, the Royal Australian Navy’s auxiliary vessel MV Stoker located the Edsall’s wreck at a depth of around 18,000 feet. The discovery was announced on November 11, 2024, by US and Australian officials, confirming the site’s identity and releasing images.

A US Navy legend was rediscovered and her glorious—but tragic—story can finally be told in full.

The Origins of the USS Edsall

Named after Seaman Norman Eckley Edsall, who famously perished in 1899 during a landing party action in Samoa, the Edsall was launched in 1920. This destroyer embodied the Interwar US Navy’s reach, patrolling distant waters from Europe to Asia. It was during the chaotic opening months of the war against Japan, however, that the Edsall etched its name into history.

USS Edsall was laid down on September 15, 1919, at the William Cramp & Sons shipyard in Philadelphia, Penn. The destroyer was part of America’s post-World War I naval expansion. Reclassified as DD-219 on July 17, 1920, she was launched on July 29 of that year, and officially commissioned under the leadership of Commander Arthur H. Rice, Jr., on November 26 of the same year. Though the ship was small, she was armed with four 4-inch guns, one 3-inch gun, 12 21-inch torpedo tubes, and various machine guns, making her a versatile escort vessel.

In 1922, after spending her early years operating off the West Coast of the United States, the Edsall deployed to the Atlantic for maintenance before joining the US Naval Detachment in Turkish Waters amid the Greco-Turkish War. There, she evacuated refugees, supported relief efforts, and navigated tense regions including the Black Sea and Aegean Sea, with port calls in Odessa, Smyrna, and Athens.

By 1925, Edsall shifted over to the Asiatic Station, arriving in Shanghai on June 22. For over a decade, she protected American interests in China and the Philippines, enduring the turbulence of warlord conflicts, the 1932 Shanghai Incident, and the onset of the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937. Summers were spent in Chinese waters, like Amoy and Tsingtao, while winters involved operations in Manila Bay. The destroyer’s extensive peacetime service drastically improved the crew’s skills for the great war that was to come.

As tensions escalated with the Empire of Japan, the Edsall, which was assigned to Destroyer Division 57 (DesDiv 57) under Lieutenant Joshua J. Nix, deployed to Balikpapan in the Netherlands East Indies on November 24, 1941. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor came almost two weeks later. From that moment on, the Edsall was at the epicenter of the Pacific Theater of World War II.

The Edsall’s Brief but Fiery War Service

Immediately following the commencement of hostilities with Japan, Edsall raced over to Singapore, searching for survivors of the doomed British Royal Navy battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse on Dec. 10. The American destroyer captured a Japanese fishing vessel en route.

From there, Edsall was ordered to escort duties for Allied convoys operating in the Pacific—including an escort mission for the USS Houston on its way to Darwin, Australia.

January 20, 1942 marked the Edsall’s first major victory in the early days of WWII near Darwin. While escorting the oiler USS Trinity, she collaborated with three Australian corvettes and a Grumman OS2U Kingfisher seaplane to sink the Japanese submarine I-124. This marked the first US destroyer to claim a full-sized enemy submarine in the war. Edsall subsequently embarked upon a series of anti-submarine patrols off Java.

On February 26 of that year, Edsall joined the seaplane tender, USS Langley, to ferry dozens of US Army Air Forces (USAAF) Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters to Java. The next day, the Langley was crippled by Japanese bombers and scuttled. The Edsall rescued 177 survivors from the Langley, which included 31 USAAF pilots, transferring most to the USS Whipple.

The Edsall’s Final Battle—and the Legend of the “Dancing Mouse”

The Edsall’s fate was sealed on March 1, 1942, in the Indian Ocean, approximately 200 miles southeast of Christmas Island. En route to Tjilatjap, Java, after the Langley rescue, she was spotted by a Japanese scout plane belonging to the IJN aircraft carrier Akagi—misidentified as a light cruiser. Akagi was the flagship for the formidable carrier strike force under the command of IJN Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo. Along with the Akagi, Japanese carriers Kaga, Hiryu, and Soryu were part of Nagumo’s carrier strike force—all four later to be sunk at the pivotal Battle of Midway in June of the same year.

The surface engagement, however, fell to IJN Rear Admiral Gunichi Mikawa’s group of battleships, the Hiei and Kirishima, and heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma. The USS Edsall was attempting to aid the oiler USS Pecos when she was spotted by the Japanese scout plane. Because of prior damage, the Edsall was forced to operate at a reduced speed.

Around 5:00 pm local time, the Japanese heavy cruiser opened fire on the Edsall from 21,000 yards. The Hiei followed immediately afterward, firing from 27,900 yards. Lieutenant Nix, the commanding officer of the Edsall, evaded the initial Japanese attack by laying smoke screens, zigzagging, and firing her four-inch guns and torpedoes. Indeed, one fusillade from the Edsall just barely missed the Chikuma.

The Japanese observers of the battle were duly impressed by Nix’s maneuvers and immediately nicknamed the Edsall the “dancing mouse” for her agile moves. Stunningly, the USS Edsall is believed to have dodged over 1,300 shells—including 297 15-inch and 844 8-inch rounds.

However, because of the effectiveness of their defenses, the frustrated Japanese commanders launched nearly 30 Aichi D3A “Val” dive-bombers roughly 57 minutes into the battle. 20 minutes later, bomb hits left the Edsall dead in the water and ablaze. Final gunfire from Kirishima and Chikuma sank her stern-first around 7:30 pm local time.

The Edsall’s Story of Tragedy—and Unyielding Valor

One-hundred and ninety-five Americans were lost aboard the Edsall. Among them were around 153 Navy crewmen plus the additional USAAF personnel Edsall had rescued from the Langley. The Navy listed these losses as “Missing in Action.”

It is believed that the Japanese heavy cruiser Chikuma rescued around eight survivors of the Edsall, and the Tone possibly rescued several more. But retrieval operations by the Japanese ships were cut short due to a submarine alert, and the IJN left any remaining American sailors to their fate.

In any case, rescue by the Japanese was even worse than being left to the mercy of the seas. The Japanese were known for their unremitting bloodlust during the war, and could not help themselves in quenching it on the Edsall’s survivors. A year after the war ended, war crimes trials disclosed that at least six identified crewmen of the doomed ship, along with potentially as many as five USAAF pilots, had been taken to Kendari II airfield on Celebes Island and beheaded on March 24, 1942. Their remains were recovered after the war and reburied in US cemeteries.

On November 25, 1945, Lieutenant Nix and the rest of his gallant crew were formally declared dead. By that point, the Edsall had been stricken from the Navy Register for years. She had also earned two battle stars for her service—one for the Philippine Islands operation and another for the Java Sea defense.

The Edsall’s story is one of unyielding valor against insurmountable odds. The “dancing mouse,” as her brutal Japanese opponents had dubbed her, exemplified the very best that the US Navy has to offer. Though lost with nearly all hands, and with survivors meeting a grisly end at the hands of the vicious Japanese aggressors, the legacy of the Edsall endures through battle stars, iconic historical accounts, and now its rediscovered wreck.

Author: Brandon J. Weichert

Brandon J. Weichert, a Senior National Security Editor at The National Interest as well as a contributor at Popular Mechanics, who consults regularly with various government institutions and private organizations on geopolitical issues. Weichert’s writings have appeared in multiple publications, including the Washington Times, National Review, The American Spectator, MSN, the Asia Times, and countless others. His books include Winning Space: How America Remains a Superpower, Biohacked: China’s Race to Control Life, and The Shadow War: Iran’s Quest for Supremacy. His newest book, A Disaster of Our Own Making: How the West Lost Ukraine is available for purchase wherever books are sold. He can be followed via Twitter @WeTheBrandon.

Image: Shutterstock.

The post USS Edsall: The US Navy’s “Dancing Mouse” Drove the Japanese Nuts appeared first on The National Interest.