Uruguay’s pragmatic and nonpartisan quest for renewable energy highlights how even small nations can achieve rapid decarbonization and economic growth — offering a powerful example for climate leadership amid global inaction.

Uruguay remains an outlier in a region beset by challenges. Like other Latin American nations, it must contend with mass migration from Venezuela, the ill effects of authoritarianism, and a growing mistrust of democratic institutions across the region, not to mention the impacts of climate change on water supply, agriculture, and natural ecosystems. Yet as one of Latin America’s most successful actors in the transition to renewable energy, Uruguay has quietly done what most can only promise: generating nearly all its electricity from renewable resources. In a world that desperately needs the decarbonization of heavy industry and energy systems on a massive scale, Uruguay offers a small, but still instructive, answer to the biggest problem facing the global politics of climate change — climate inaction.

Two decades ago, Uruguay was in the midst of an energy crisis. Heavily dependent on fossil fuel imports and exposed to volatile energy prices, it suffered blackouts and growing public frustration. The turning point came in the mid-2000s, when a combination of droughts and rising fuel costs convinced policymakers that something had to change. Uruguay’s transition to clean energy was primarily driven by this difficult environment, as well as investments in hydropower and wind energy as part of a strategy led by Dr. Ramón Méndez Galain, Uruguay’s national director of energy from 2008 to 2015. In particular, wind power grew at an extraordinarily fast pace, helping to reduce Uruguay’s increasing reliance on hydropower and vulnerability to drought.

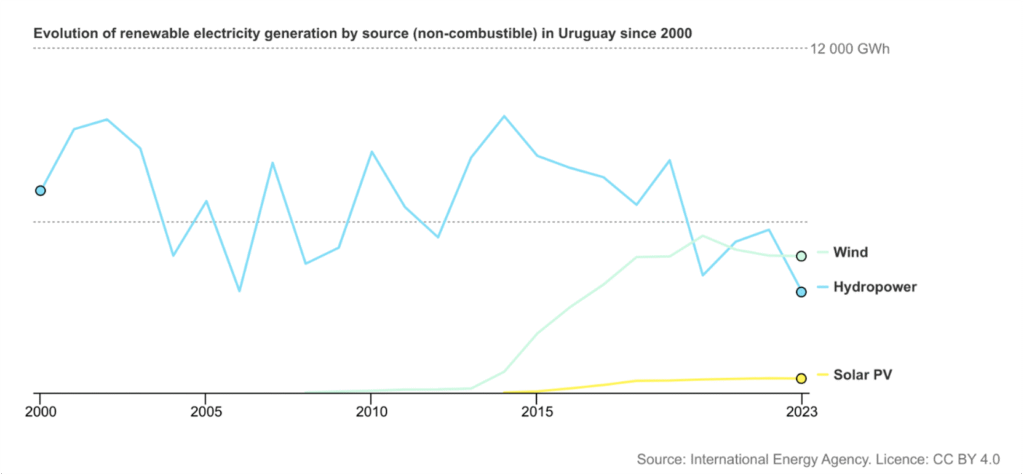

Uruguay was able to put climate action at the center of its energy and economic policy by increasing its renewable energy generation through its National Energy Policy 2005-2030, developed and launched under the governments of Tabaré Vásquez and José Mujica. It opted for a complete overhaul: diversify supply, incentivize private investment, and make renewable energy a pillar of its national economic policy. According to the International Energy Agency, Uruguay managed only three GWh of wind power generation in 2008 compared to 5,000 GWh in 2020, an 1,800-fold increase in just 12 years. Thanks to major public and private sector investments, the renewables share of electricity generation reached a stunning 98 percent in 2023.

Image courtesy of the International Energy Agency.

Decarbonization would obviously be far more consequential for far larger emitters like the United States and China. Latin America represents less than 10 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and deforestation is by far one of the largest drivers of regional emissions. Even so, cuts to global emissions will fall short of the levels needed to meet international targets if left to large countries alone. That is why Uruguay’s experience is so important, as it showcases Latin America as a potential renewable energy powerhouse.

In less than ten years, Uruguay channeled over $7 billion — about 15 percent of GDP — into renewable energy infrastructure. Wind farms sprouted across the Pampas, Uruguay modernized hydropower dams, and solar energy began feeding the grid, with significant potential for further scaling up of photovoltaic projects. Today, wind power accounts for about 45 percent of electricity generation, hydropower still provides a steady baseline, and biomass from agriculture fills in the gaps. All of this has provided remarkably stable pricing, despite the challenges of intermittency.

Most importantly, Uruguay’s quest for renewable energy has been largely nonpartisan, propelled most recently by a center-right government that sought innovations in strategic sectors such as green hydrogen and green bonds. Yes, the country’s size and geography helped, but good governance and political consensus mattered most. Looking forward, the new center-left government of Yamandú Orsi, which took office earlier this year, is discussing a potential consolidation of state entities to further the energy transition and supercharge the development of green hydrogen. It is also likely to extend the National Energy Policy to 2050 to provide international investors with greater assurances of the country’s commitment to decarbonization.

An important question for today’s climate and energy debates is how the Uruguayan experience could influence others in the region and beyond, such as Ecuador, which suffered 14-hour blackouts in 2024? Likewise, might Uruguay’s example motivate its larger neighbors — Argentina and Brazil — to accelerate their adoption of renewable energy technologies?

The Uruguay Effect

Nestled between South America’s largest economies, Argentina and Brazil, Uruguay is easily overshadowed. In the case of renewable energy, however, the country of 3.4 million people has a chance to influence the energy destinies of its giant neighbors. After all, Argentina and Brazil possess significant amounts of critical minerals and rare earth elements, as well as ample wind and solar resources, yet neither has met its clean energy potential.

In Argentina, President Javier Milei has prioritized the Vaca Muerta shale play — the fourth largest in the world — as an important source of foreign direct investment and an economic motor during a period of stabilization and reform. Despite dramatic increases in oil and gas output, Argentina recently faced a currency crisis, leading to a controversial US bailout. Going forward, it could diversify its energy strategy by attracting investments to modernize its energy infrastructure with an emphasis on renewable energy and transmission. The country’s investment incentive mechanism, known as RIGI, is a perfect tool. Importantly, Argentina and Uruguay share a similar wind resource in the Pampas. And if investors need further incentives, Argentina could point to Uruguay’s success next door.

For its part, Brazil is hosting the UN climate summit known as COP30. It is eager to demonstrate its climate and environmental bona fides even as it moves to become the fifth-largest oil producer by the end of this decade, with state-owned Petrobras recording record oil exports. Like Argentina, the sheer size and diverse nature of Brazil’s economy mean efforts to quickly channel capital to wind and solar projects could yield important dividends.

Indeed, Uruguay has provided the road map, demonstrating how pragmatic and nonpartisan strategies can produce rapid decarbonization and economic competitiveness on a national scale. Given US reversals on climate policy and disagreements between Washington and Brussels over the transition to renewable energy, there are few large countries that appear ready to adopt Uruguay’s model. Even so, Uruguay could motivate countries in Latin America to make serious commitments at COP30 and to pursue ambitious energy transformations that would offer additional examples for other regions where the energy transition is stalling at this critical moment for the health of the planet.

About the Authors: Anders Beal and Beatriz García Nice

Anders Beal is a non-resident fellow at the Stimson Center Latin America Program and a doctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki. From 2013 to 2014, he served as Assistant to the Executive Secretary in the Chilean American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham Chile), where he supported bilateral cooperation on energy issues through the US-Chile Energy Business Council. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Spanish & Economics and master’s degree in Global Policy from the University of Maine.

Beatriz García Nice is a non-resident fellow at the Stimson Center Latin America Program. Before that, Ms. García Nice worked for the Organization of American States – Inter-American Committee against Terrorism (OAS/CICTE) managing the committee’s operations portfolio, the U.S. Department of State with the Consular Bureau at the US Embassy Santiago, Chile, and as a former specialist with the International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Bureau (INL) at the US Embassy Quito, Ecuador. Ms. García Nice received a BA in International Relations and Political Science from the Universidad de las Américas-Puebla (UDLAP) and the Université Jean Moulin Lyon III, and a MA in Security from The George Washington University.

Image: Shutterstock/Alii Sher