A recent news article from PillarCatholic reported on a public spat between the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the Catholic schools of that country. In a circular dated July 14, 2025, the education ministry ordered all Congolese schools to stop excluding pregnant girls during the new academic year.

About half of the DRC’s population is Catholic, and about a quarter of all schools in the Congolese education system are Catholic schools.

The priest who serves as the national coordinator of Congolese Catholic schools wrote a letter a few days later to Catholic school administrators. He explained that a previous agreement between Catholics and the government takes precedence over this new directive and that girls in Catholic schools who become pregnant will continue to be transferred to state-run schools, following the existing practice. In a video on social media, the general secretary of the National Episcopal Conference of Congo stated, “It’s not a question here of refusing, of rejecting students who are in this situation. … One of the hallmarks of our schools is discipline in matters of morals, among other things.”

Such a response to teenage pregnancy might seem shocking to Western sensibilities. A more common response by a Catholic school in the US would involve encouraging the pregnant girl to complete her education by remaining in her Catholic school or perhaps homeschooling for the sake of schedule flexibility. One would hope that in any Catholic school in any country, the young mom and her parents or guardians would have a fruitful discussion about Catholic faith and morals with school staff, as well as talk about her vocational plans and the practical matters involved in a healthy pregnancy.

But it is easy to see why it would be difficult for a Catholic school in the US to ask the young mom to leave school. After all, with easy access to abortion available through all nine months of pregnancy somewhere in the country, it would be dangerous (to the unborn baby, at the very least) to imply to a student that she could be forced to leave school if she were discovered to be pregnant.

In defense of the Congolese government, the directive is designed to ensure that girls receive an adequate education. Only about half of their female students currently complete secondary education, apparently due to teen pregnancy and marriage.

But the response of the Congolese Catholic schools to this situation is interesting. Since pregnant girls can still receive an education at state schools, their practice of asking those girls to leave Catholic schools allows those schools to emphasize that Catholic students are expected to live lives of virtue. Granted, abortion is also legal in the DRC, so there is a danger that this practice could encourage young moms to seek abortions and end the lives of their unborn children.

But maybe Congolese Catholic schools can establish this higher standard of moral behavior for their students because Catholics make up half of the country’s population. And, one could argue, their Catholic parents expect it.

Since the advent of the Sexual Revolution, it has become a common belief that no one should suffer any negative consequences for any sexual act. Consent is all that is required to make any act “right,” at least by modern standards. But relativist standards are not God’s standards.

One historical example demonstrates another situation from a different culture and time that might be helpful in this discussion.

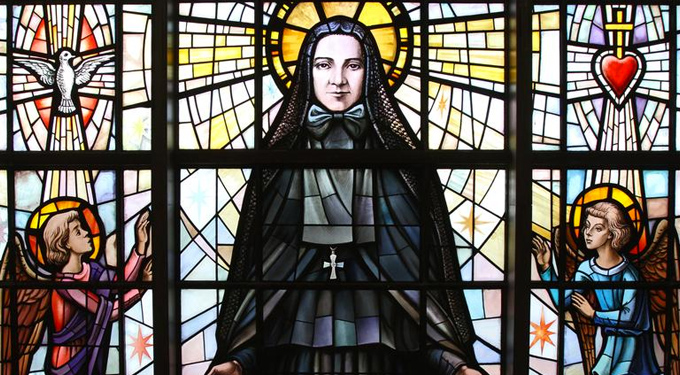

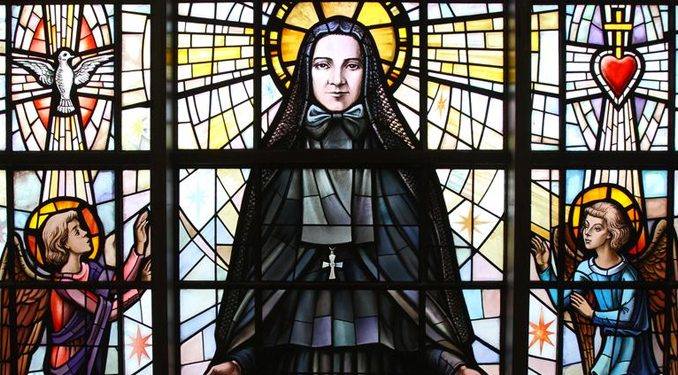

In 1891, religious foundress Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini (1850-1917) was invited to come to Granada, Nicaragua, and establish a school. The wealthy citizens of that city had decided that they wanted her Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to educate their daughters. Mother Cabrini knew that once she opened a school for the children of the rich, she could develop the funds, contacts, and reputation required to open schools for the children of the poor as well.

Within a few months of her arrival, Mother Cabrini realized that she had a serious problem. While there were plenty of families who wanted to register their children in her school, most of those children were illegitimate. Although the population of Granada was heavily Catholic, the residents of the city seemed not to know about the existence of the Sixth Commandment. Even prominent citizens kept mistresses and did not bother to marry the mothers of their children. Local church leaders recognized the problem existed, but had simply thrown up their hands.

Mother Cabrini could have ignored the problem, but she was far too serious about her faith in Christ and His Church to condone a widespread disregard for the sacrament of matrimony. She let it be known that her school would not accept illegitimate children.

At first, some parents were merely irate. Public outbursts of anger against her accelerated to threats and violence, as groups of men surrounded her convent night after night, firing their guns and banging on the doors to try to scare her into backing down. Instead, she simply accepted the fact that she might be assassinated.

But she did not give in.

And, wonder of wonders, then her enemies began to repent—or rather to get married. It started with one nobleman who legitimated his daughter, and then others followed suit. What the entire Catholic hierarchy of Nicaragua could not accomplish, one religious sister did by fearing God’s judgment more than the threats of men.

This example from the life of Saint Frances also points out the importance of the person who is often omitted from the discussion of how best to help an unwed mother: the child’s father. As Marvin Olasky and Leah Savas point out in their examination of the state of unwed motherhood in seventeenth-century America:

Community pressure on young men meant that pregnant, unmarried women could generally count on marriage before going into labor. If young men hesitated, older men intervened. They rarely needed shotguns, but every father had one. To be married under shotgun pressure carried no disgrace, and most marriages were by (at least informal) parental arrangement anyway.

The Story of Abortion in America also points out that abortion became a more popular response when girls and women moved to large cities during the Industrial Revolution. Separated from their families, young moms did not have the financial ability to support themselves, and they lacked a community of men to “encourage” the fathers of their children to take responsibility for their actions.

These four circumstances are not as unrelated as they might seem. In all four situations, Catholics have made decisions about how to respond to those who have failed in the virtue of chastity. Since that failure could happen (and probably has happened) to every adult, it should not be that difficult for us to find ways to help others with compassion as well as faithfulness.

It is tempting to be scandalized that Catholics in different cultures and times respond differently to similar moral issues. Rather than seeing the Congolese Catholic hierarchy as backward or unsympathetic to the problems of teen mothers, Westerners can use their example to better understand Western culture and challenge its weaknesses.

By God’s grace, we can learn from one another how to support the physical and emotional well-being of a pregnant teen and her unborn child without forgetting their eternal salvation—and try to love them both.

Endnotes:

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.