I must confess that I approach the writing of this article with some apprehension, as months have elapsed since the canonization of Pier Giorgio and numerous reflections have already been penned.

Many see in Pier Giorgio a sanctity that wears modern clothes and shares in the fabric of our daily lives—and even try to make of him a contemporary philanthropist. It is not uncommon to find such observations as:

- “His story contains no miracles, visions, or other supernatural phenomena—only an unwavering response to God”

- “Ordinary holiness”

- “Champion of the Poor”

- “Considered one of the ‘social saints’”

Really? Such characterizations are, alas, generalizations—half-truths at best. I should therefore like to address these views.

Is sanctity truly within arm’s reach? I argue that it is not; the gate is narrow, the path climbs steeply uphill, and there are no shortcuts.

We know nothing of his most intimate relationship with Jesus. I would venture to say, with almost absolute certainty, that since Pier Giorgio kept his mortal illness hidden even from his family, he was even more unwilling to expose his inner spiritual life. In this, too, the true humility and deep love between the Creator and His creation are revealed.

In performing acts of charity, he always chose anonymity, seeing his service as a response to Christ: “Jesus visits me every morning in Holy Communion. I return it to Him, with my poor means, by visiting the poor.”

What we do manage to uncover, however, seems to be only the tip of the iceberg. Pier Giorgio never missed the night adorations, and witnessing him during these vigils—his edifying composure, absorbed in prayerful recollection—was striking, standing in complete contrast to the lively energy he displayed among his companions. At times, he would pray for hours through the night, then emerge at dawn to join his friends in joyful shouts.

Pier Giorgio’s life was oriented by an intense spiritual depth. The daily Eucharist was the central point of reference in his journey. So as not to miss this appointment, he rose early and would forgo excursions if they prevented him from attending Mass. He was nourished each day by meditation on St. Paul’s Hymn of Charity (1 Corinthians) and by the writings of St. Catherine of Siena. For him, receiving Communion meant sharing in intimacy with Jesus; he was often seen in the pew, absorbed in a profound recollection from which nothing could distract him.

While he was known for his lively spirit and sense of humor, Pier Giorgio’s demeanor before the Eucharistic Lord was entirely different. At such moments he would often remain completely still, not moving a muscle. Even when hot wax from a candle dripped onto his hand, he seemed not to notice.

From an early age, Pier Giorgio displayed a spiritual maturity well beyond his years. His mother introduced him to the fundamentals of the Christian Faith, nurturing in him a quiet yet deep-rooted sense of devotion. At around twelve years of age, he sought his mother’s permission to receive Holy Communion daily, and after four days of earnest pleading, she finally relented.

Documentary biographies and the canonization committee record that Pier Giorgio carried the Rosary constantly and made pilgrimages to numerous Marian shrines. It may be presumed that, after the manner of Mary, he too “kept all these things and pondered them in his heart” (Lk. 2:19).

For him, the most marvelous army consisted of young people following the Eucharist. In a letter written in 1922, Frassati describes “more than 20,000 enthusiastic young men marching before the Blessed Sacrament through the streets of Novara.” He believed that Christians should draw courage from daily encounters with Christ in the Eucharist and through prayer, to face the world and bring about the “moral regeneration” that society so greatly needed.

On May 28, 1922, Pier Giorgio entered the Order of Preachers as a Dominican tertiary, taking the name Fra Girolamo in memory of Savonarola. His membership was in the Dominican laity—which prescribed among its observances the daily recitation of a special Office in honor of the Madonna.

In a 1925 address to FUCI students, Pier Giorgio called on young Catholics to take an active role in transforming the world, urging them to “cooperate generously in the moral regeneration of society worldwide so that a radiant dawn may break, in which all nations recognize Jesus Christ as King not only in words but in all their people’s lives…”

Only shortly before earning his engineering degree did Frassati contract poliomyelitis—the disease that would claim his life on July 4, 1925, at the age of twenty-four. His doctors later speculated that he had caught the infection while serving the ill.

When Pier Giorgio’s body was exhumed in 1981, it was found to be incorrupt—a striking sign that may well point to an extraordinary holiness, even among the saints.

It is not difficult to imagine that, had Pier Giorgio lived in our own time, he should have met the draconian restrictions of the recent COVID-19 pandemic in the State of Victoria, Australia, with the same spirit of discernment, quiet courage, and resilience that marked all his choices—guided first and foremost by conscience than by conformity. “We must obey God rather than men ” (Acts 5:29).

I shall once again draw on a brief quotation from a much longer statement by his sister, Luciana. It concerns an aspect that is notoriously difficult to master, both for adolescents and for those of mature years—purity:

You might underestimate Pier Giorgio’s charity, piety, or intelligence, but his purity was evident even to the least observant onlooker. It was his most visible virtue; his whole being was imbued with it, and not even his modesty could conceal it…

At the same time, one senses a certain tendency—among both clergy and laity—to shape Pier Giorgio into a flawless emblem of social virtue, emphasizing above all his care for the poor, the excluded, and the marginalized. Nevertheless, such a perception of the saintly youth from Turin seems to lack a crucial understanding: the charity he practiced was a means of attaining holiness, not an end in itself. Pier Giorgio acted out of love for Christ, whom he recognized in every human being. It can safely be said that his path to sainthood was multifaceted.

In concluding my reflections, I suspect that this way of interpreting the road to holiness may have its roots both in liberation theology, which has permeated certain ecclesial circles, and in the Marxist thought that has become ubiquitous in almost all American universities, where assistance to the disadvantaged is deemed as the supreme moral imperative. As St. John Paul II points out, such an approach reduces the Church’s mission to its purely horizontal dimension, thereby denying her transcendental orientation.

[The] Church receives the mission to proclaim and to establish among all peoples the Kingdom of Christ and of God. She becomes on earth the seed and beginning of that Kingdom. (Lumen Gentium, 5)

Pier Giorgio has become, for all of us, a beacon showing how one’s formative years may be well lived. Like St. Stanislaus Kostka, he covered a great deal of ground in a short time, and God took his sanctified soul to heaven while he was still young, as a vivid image of goodness and perfection in its fullness.

St. Pier Giorgio Frassati, ora pro nobis!

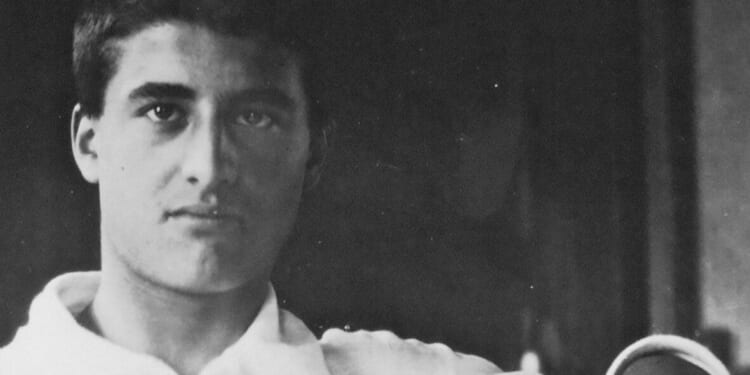

Image from Wikimedia Commons