One of the ironies of Donald Trump’s first presidency is that a former real-estate investor and landlord enacted an unprecedented federal eviction ban. In early 2020, as Covid lockdowns paralyzed the country, Trump signed the CARES Act, placing a moratorium on evictions for any rental properties with federal loans or assistance. Despite the unprecedented scope of the eviction ban and billions in aid, tenant-advocacy groups blasted Trump for doing too little to prevent what headlines called an impending “eviction tsunami.” While landlords sued to overturn the expanding moratorium, states and cities imposed their own tenant protections, including broad eviction bans and numerous laws rewriting landlord–tenant relationships.

Many of these measures outlasted the pandemic, shifting the legal balance sharply toward tenants and jeopardizing the financial stability of landlords—from small property owners to large nonprofit housing operators. The barrage of new legislation won’t benefit tenants the way advocacy groups that lobbied for the laws claim, and it won’t make housing more affordable. Instead, the laws provide so many extraordinary protections that they’ve cultivated an attitude among tenants of not paying rents and of using the intricacies of new laws and programs to game the system at the expense of its financial stability. Research shows that such policies, by discouraging real-estate investment, are limiting housing supply and driving up rents.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Alarmed by the consequences, some local officials are now pushing for reforms. In tenant-friendly Washington, D.C.—where even nonprofit affordable-housing providers face significant losses—Mayor Muriel Bowser recently admitted, “What we want is for people to pay their rent.” Without that, America’s housing crisis will only deepen.

Covid lockdowns hit most U.S. businesses hard, but renter-favoring federal and local policies made the pandemic especially devastating for residential landlords. The biggest blow came from a series of broad national eviction moratoriums for nonpayment of rent, starting with the March 2020 passage of the CARES Act, which included a 120-day national eviction ban. Similar prohibitions followed from the Centers for Disease Control, which remained in effect until August 2021, when the Supreme Court ruled that the CDC lacked the authority to impose such policies without congressional approval.

Further, 43 states and hundreds of local governments used emergency powers during Covid to enforce their own wider proscriptions of tenant removals. While some lasted for just a few months, others extended for years. Eviction bans lasted in New York and Minnesota until 2022, and in parts of California until March 2023.

While eviction bans aimed to protect vulnerable tenants, they disproportionately harmed the small landlords who form the backbone of the affordable rental market. Operating in low-rent areas with slim profit margins and limited capital, such owners often struggle to endure sudden downturns. The blanket bans frequently failed to distinguish between renters who couldn’t pay due to lost income and those who could; widespread nonpayment ensued. A summer 2021 census survey estimated that 6.5 million households were behind on rent, many in small buildings of one to four units, typically owned by mom-and-pop investors. Nearly a third of these landlords earn under $90,000 annually; more than a quarter are black or Hispanic.

By August 2021, when the national moratorium ended, a Goldman Sachs study estimated that landlords were owed up to $17 billion in back rent. A National Apartment Association lawsuit against the CDC’s eviction ban claimed that landlords had absorbed nearly $27 billion in losses. Even large, government-subsidized nonprofit housing projects saw a steep and lasting decline in rent payments. The New York City Housing Authority’s rent-collection rate fell from 95 percent pre-pandemic to 60 percent in 2023—long after Covid lockdowns had ended—resulting in more than $500 million in unpaid rents.

To mitigate these losses, the government launched emergency rental-assistance programs—but slow implementation and bureaucratic hurdles left many landlords waiting months for relief. In December 2020, Congress allocated about $46 billion for landlords, but state and local governments were tasked with distribution and lacked the infrastructure to do so efficiently. By the following summer—nearly 18 months after the first eviction moratorium—less than $5 billion had reached landlords. Some states also required both tenants and landlords to file the applications for reimbursement, but many tenants, shielded from eviction, simply ignored landlords’ requests to participate.

The bans encouraged widespread rent refusal, even among those who were still working or had received enhanced government benefits, such as extended unemployment insurance. A Las Vegas landlord reported being owed $10,000 in rent by a tenant who had retained his $80,000-a-year job throughout the pandemic, but he could do nothing about it. “I feel the state has failed me,” he wrote. In New York State, the rental assistance program quickly exhausted federal funds, yet tenants were allowed to keep filing applications, in case new money became available. Even after the state lifted the eviction ban, landlords were barred from evicting tenants who had filed for aid until their applications were processed—despite the program running out of funding.

The revenue shortfalls that property owners suffered during Covid significantly affected the financial viability of rental housing, particularly for smaller landlords. A National Institute of Medicine study on the impact of pandemic lockdowns on landlords reported a notable rise in disinvestment in their properties. More rental buildings went up for sale as the pandemic progressed, suggesting that many owners were considering exiting the business.

Meantime, rents jumped in many markets, as owners who kept their buildings tried to build back their financial stability amid soaring inflation, which raised their costs on everything from energy to building materials to labor. In California, a real-estate broker, Ken Calhoun, noted in a newspaper column a significant decrease in available single-family homes for rent, as owners opted to sell. “California needs more rental opportunities that can best be provided by individual housing providers,” Calhoun argued. “Lawmakers should be promoting policies that encourage investments in rental homes. However, they have declared war on housing providers.”

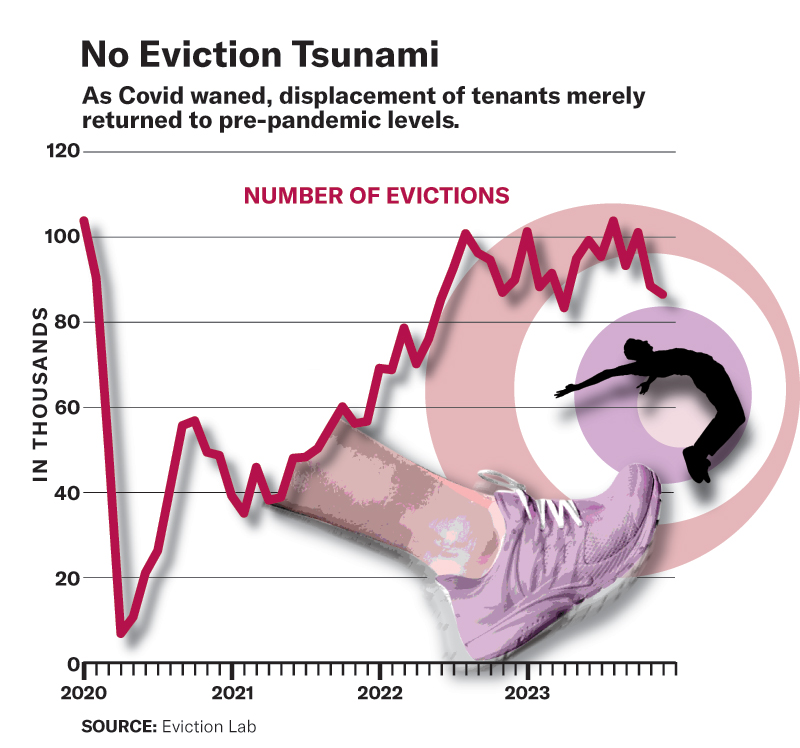

Landlords have received little sympathy for their challenges. As eviction bans expired or were overturned, local newspapers predicted massive tenant displacement and a surge in homelessness. Few reports provided crucial context: during the pandemic, eviction bans caused tenant displacement to drop well below historical averages. After the CARES Act passed, for example, evictions fell to just 8 percent of pre-Covid levels in April 2020, and they stayed below 20 percent through spring and summer of that year. Even after the Supreme Court overturned the national ban, state restrictions kept evictions below 60 percent of typical levels until late 2021. While evictions briefly exceeded pre-pandemic levels in March 2023, they have since stabilized at normal levels. In reality, post-pandemic evictions simply returned to historical norms.

Sensational headlines and reports from tenant advocates about a national crisis have unleashed a different kind of tsunami: hundreds of new state and local laws marketed as tenant protections. In just three years, local governments have passed 217 measures across 16 categories, including caps on rent increases, restrictions on lease nonrenewals, mandates for landlords to participate in the federal housing-voucher program, and strict limits on security deposits and fees. Pre-Covid, 288 such laws existed nationwide. In other words, since the pandemic, states and localities have nearly doubled the legal framework governing residential leasing. In Illinois alone, up to a dozen new laws regulating landlords took effect on January 1. Many, such as those extending eviction trials and appeals or limiting security deposits, increase risks for landlords. While some measures—such as providing tenants with state-funded legal counsel or banning landlord “retaliation”—may seem reasonable, the details often reveal unintended consequences. These laws can make it harder for landlords to raise rents, allow nonpaying tenants to remain in properties longer, and reduce landlords’ discretion in choosing tenants.

The rise of so-called tenant-friendly legislation will almost certainly make America’s housing affordability crisis greater. In a recent study, finance and business school professors from three universities used a “tenant-friendly” index to look at the levels of regulation of landlords among the states. The study found that those places with the heaviest regulation reduced evictions, but at the cost of a smaller supply of available housing, higher rents for everyone else, and increases in homelessness. “It is essential for policymakers to understand the delicate balance between the strictness of landlord regulations, evictions, and rent affordability, to achieve their goal of increasing tenants’ welfare,” the authors concluded.

They also observed that, until their study, economic research on evictions had largely ignored the connection between tenant protections and housing affordability. That’s even truer about public-policy debates. Aside from warnings from the real-estate industry itself, few politicians or media voices have raised concerns about how a surge of new tenant laws might influence rental costs and housing availability.

One can just look at rent levels nationwide to see the consequences. Jurisdictions often rated as the most tenant-friendly are also among the country’s priciest. One recent study, for instance, listed California, New York, and Massachusetts among the top tenant-friendly states—and all ranked in the Top Ten for highest rents. California’s average rent is over $500 a month above the national rate, while Massachusetts’s is $262 above the average. By contrast, landlord-friendly states like North Carolina, Texas, Alabama, Georgia, and Indiana—frequent picks for real-estate investors—consistently have rents below the national average. Such correlations raise the question: Why isn’t rent itself used as a measure of how tenant-friendly a state or city is, rather than its tenant regulations?

Migration patterns reveal a similar disconnect. Residents are leaving many tenant-friendly states; the most landlord-friendly are attracting newcomers. Landlord-friendly spots are also where investors are putting money to build new housing—helping to keep those markets more affordable. A 2023 study of metro areas with the most permits for multifamily housing shows that landlord-friendly markets in Texas, North Carolina, and Florida are leading in new housing construction, while tenant-friendly markets like New York, California, and Illinois lag behind, with developers planning the fewest new units relative to population size. As one investor wrote on SparksRental, a real-estate investing website: “I will never invest in tenant-protective cities or states again. It’s just not worth the headaches, red tape, and endless eviction process when the tenant breaks the rules, and you pay the price.”

Few policies illustrate the negative unintended consequences of the new tenant legislation better than the resurgence of rent-control and rent-stabilization laws. As Jason Furman, former head of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, recently told the Washington Post, “Rent control has been about as disgraced as any economic policy in the tool kit.”

Consider New York City. Rent control, in effect since World War II, and rent stabilization, introduced in 1969 for newer buildings, have wrought havoc on the city’s housing market. During the inflationary 1970s, landlords of smaller rental properties, unable to raise rents to cover rising costs, abandoned their buildings, resulting in the loss of 300,000 housing units in just a decade. This crisis followed a major drop in housing construction after New York State gave the city authority to enforce rent control in 1962. As real-estate investment plummeted, new housing starts fell from 70,000 units annually in the early 1960s to as few as 10,000 by the mid-1970s. Housing production rebounded in 1997, after Republican governor George Pataki successfully pushed for the de-control of high-priced apartments, sparking a surge in new building that lasted until 2008. But after Democrats regained control of Albany that year, they curtailed de-control, triggering another housing slump.

Yet, despite the well-documented consequences of rent control, states and cities across the country continue to adopt it, often compounding years of restrictive building regulations and zoning rules that have already stifled housing production and driven up rents. In 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom signed statewide rent-control legislation, described by the media as “safeguards” against rent hikes. The law, introduced in a state with arguably the nation’s worst housing shortage, caps rent increases at 5 percent plus inflation for buildings older than 15 years and prohibits landlords from refusing to renew a lease without proving that the tenant violated its terms—a form of “just-cause” protection that further limits landlords’ control over their own buildings. California also lets municipalities impose stricter rent-stabilization measures. In the past three years alone, 16 California communities have decreed their own rental caps, joining long-standing strongholds of regulation like San Francisco.

Oregon followed California’s lead in 2019, approving statewide caps on rent increases and just-cause limits on evictions. In states without statewide rent regulations but where localities can impose their own, municipalities are rushing to act. Minneapolis voters approved a change to the city charter in 2021, limiting rent increases, joining neighboring St. Paul. In New Jersey, another state where zoning restrictions have contributed to shortages of multifamily housing, dozens of cities, including Newark, Elizabeth, and Atlantic City, have adopted rent controls.

Most recently, Maryland’s two largest counties, Montgomery and Prince George’s, have limited rent hikes to the lower of either 6 percent annually or to the rate of inflation plus 3 percent. But such laws often fail to account for rising landlord costs, which don’t always align with inflation and can outpace it. This can lead owners to defer maintenance, degrading housing quality and limiting availability. In New York, for instance, a recent study found that more than 24,000 rent-stabilized apartments sit vacant, largely because landlords lack the capital to renovate them.

As landlords struggle to regain their financial footing, they face new forms of costly tenant-friendly legislation. Nationwide, eight states and 23 municipalities have passed right-to-counsel and eviction defense fund laws, subsidizing legal representation for low-income tenants. Tenant groups argue that these programs prevent evictions by leveling the legal playing field, but they’ve wound up clogging trial dockets in many municipalities. Tenants who might previously have negotiated settlements with landlords now often opt for full trials—at taxpayer expense—leading to longer waits for eviction proceedings. Combined with pandemic-related court backlogs, these programs have extended hearing wait times to six months or more in cities like Seattle and New York. In most cases, the tenants pay no rent as time grinds on. And even if the tenants eventually get evicted, the landlords are unlikely ever to recover money they’ve lost while waiting for the courts.

Making these delays even more burdensome for owners, many states and municipalities have also restricted the amount of a security deposit that a landlord can demand on a rental. In California and New York, the limit is just one month’s extra rent—exposing the landlord to enormous losses in extended evictions.

Some laws are so onerous that their legality is questionable. A prime example is “source of income” protection legislation, which prevents landlords from refusing tenants who rely on government programs to pay rent, especially federal Section 8 housing vouchers. These laws effectively force landlords to join the voucher program, which Congress originally intended to be voluntary. Participation means that landlords must comply with various conditions, including granting federal officials “unfettered access” to their properties and records, which, some legal experts say, violates landlords’ Fourth Amendment protections against warrantless searches and seizures. Landlords also report that the application process is cumbersome and that federal inspectors often demand exorbitant repairs, exceeding local building-code rules. As many as seven in ten landlords in some markets refuse to participate in the program. (In his May 2 budget proposal, President Trump proposed major cuts to the Department of Housing and Urban Development that would include essentially eliminating Section 8.)

In some places, landlords have successfully challenged these mandates. In 2021, Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court unanimously struck down Pittsburgh’s source-of-income law, ruling that state law does not authorize cities to compel landlord participation in a voluntary federal program. At least five other court cases nationwide have similarly invalidated or weakened these laws. But for now, anyway, 17 states still compel landlords to accept Section 8 vouchers.

Landlords argue that these measures will worsen the country’s housing affordability crisis. Some local officials have agreed and begun to reverse course. Washington, D.C., one of the nation’s most tenant-friendly jurisdictions, offers an example. The city had extended its Covid-era tenant emergency-aid program beyond the end of the pandemic, letting renters stop paying while their applications were under review. Ballooning debts followed, threatening even subsidized nonprofit housing providers. One study found that unpaid rent for affordable-housing operators surged from $10 million in 2020 to $100 million last year, with arrears projected to grow by another $50 million this year. As many as 20 percent of tenants still hadn’t resumed rent payments that they had frozen during the pandemic. “We may be facing a catastrophic failure of our rental housing providers,” warned one real-estate official. In response, the city rolled back some anti-eviction protections last October to make it easier for landlords to remove tenants.

Some states and cities, including Maryland, Indiana, and Philadelphia, are experimenting with free mediation services for landlords and renters in eviction proceedings, in lieu of full court trials. The programs hope to ease court backlogs. In Maryland, a pilot initiative resulted in more than 80 percent of cases getting settled outside of court. That’s proved far more efficient than taxpayer-financed legal representation that leads to lengthy court delays. But the programs are often optional, and too few exist so far.

With a new administration, the federal government has an opportunity to reassess these policies and address the causes of the housing crisis. President Biden supported the trend of tenant-friendly laws in the states and even proposed a national rent-control law. Now, with real-estate developer Donald Trump back in the White House, the calculus has shifted. If Trump has learned from his first presidency, he could significantly alter the landscape—and indeed, steps he has taken already, such as the proposed elimination of Section 8, suggest that he intends to do so. He should also work to streamline and reform the plan, ensuring, for example, that federal inspectors don’t impose requirements on landlords that exceed local building codes. Reforms should focus on making the initiative more appealing to landlords to encourage voluntary participation.

As president, Trump will oversee a federal government that provides nearly $50 billion annually to states and localities to support affordable-housing efforts. Much of this funding goes to states with some of the nation’s most restrictive and costly housing policies, such as California and New York. These policies create a counterproductive cycle: rising costs, declining affordability, and still more demands for federal funding to address problems caused by states’ own regulations.

The Trump administration should consider tying federal housing funds to reforms that unleash housing production. Many states and cities impose costly, politically driven mandates, such as requiring unionized labor or extensive environmental reviews that benefit consultants and lawyers but drive up costs. A Government Accountability Office study found big disparities in the cost of subsidized affordable housing, with median costs ranging from $126,000 per unit in Texas to $326,000 in California. Federal reforms should aim to close these gaps by curbing the political exploitation of housing subsidies.

The rise of tenant-friendly legislation is more than just a headache for landlords. It’s also a potential nightmare for tenants, as investment in rental housing slows, availability declines, and rents go up. The second Trump administration wants to address many pressing issues in its early months, but Trump himself, with his background, must understand the threat that America’s economy faces from this new age of anti-landlordism.

Top Photo by Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images News via Getty Images

Source link