Washington’s debate over SBIR’s future risks gutting America’s seed fund. Tying success to government adoption alone would strangle innovation and drive away private-sector pioneers.

The current Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) reauthorization fight is simple. Senate Republicans, led by Chairwoman Joni Ernst (R-IA), want reform. Senate Democrats, led by Ranking Member Ed Markey (D-MA), prefer the status quo. Meanwhile, the House just wants a clean, one-year extension.

The SBIR program gives small companies early-stage money to turn promising research into working products. Given the importance of SBIR to defense innovation, well-intentioned intermediaries are trying to bridge the political divide by proposing that future SBIR funding be tied to a single metric: whether companies transition technology directly to a government Program of Record.

The SBIR program needs guardrails and tighter metrics, like Senator Ernst’s proposal to cap the total lifetime awards to so-called “SBIR Mills,” companies that treat SBIR awards as their main business model instead of as “seed” funding, as the program was intended. Yet we cannot turn SBIR into a single-track race, as those in the middle suggest. It will shrink the SBIR pipeline to only what already looks safe. That’s not innovation. It’s paperwork.

The False Promise of One Metric

There are two types of transition.

- Government pull: The technology matures into something a federal buyer can adopt.

- Commercial pull: The technology succeeds in private markets, proving value and maturing outside government risk.

The second path (commercialization) is where America wins twice. A company that survives the private market brings back mature technology that the government can later buy without having spent taxpayer dollars to finish development.

Using government transition as the sole standard of success ignores this. It would turn SBIR into a narrow contracting pipeline instead of the national innovation engine it is meant to be. It’s likely to drive away the very entrepreneurs we need.

Commercialization Is Not a Loophole

According to the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), roughly one-third of SBIR-funded firms later sell products commercially or to the government. Those that succeed in private markets multiply taxpayer investment through private capital. Also, according to the NAS, every $1 of SBIR funding generates up to $7–$9 in follow-on investment or revenue.

That is not failure. It’s leverage.

The Real Distortion Risk

If Congress ties SBIR success solely to government adoption, the distortion will be immediate and obvious.

- Companies will chase safe, incremental projects with a guaranteed government customer.

- Agencies will over-engineer “transition plans” to score political points instead of cultivating true innovation.

- Private investors will walk, since there’s no signal of commercial viability left to de-risk their bets.

In short, we’ll recreate the same slow, insular industrial base that SBIR was meant to fix.

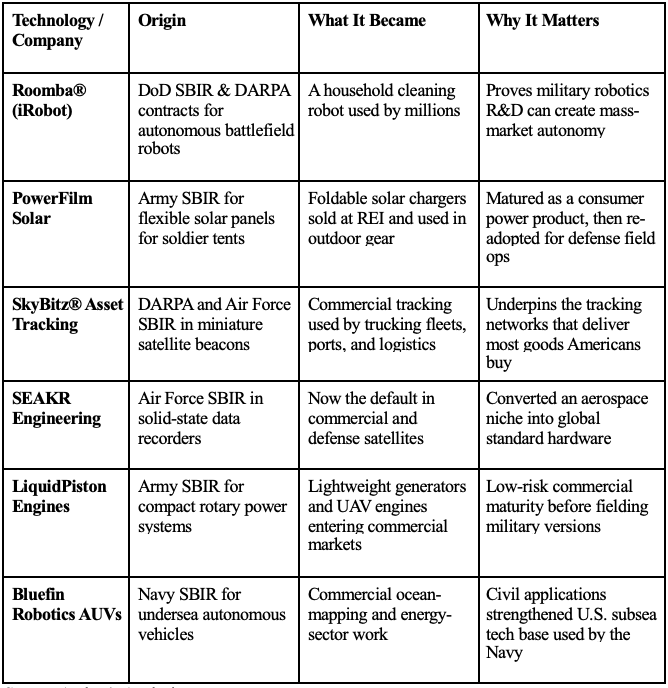

SBIR Seeds That Grew into Everyday Life

Most Americans have never heard of the SBIR program, yet they use or benefit from it daily. America’s “seed fund” quietly launched technologies that matured in the commercial market first, then came back to strengthen US defense.

The Lesson:SBIR wasn’t designed to feed the Pentagon’s procurement pipeline. It was designed to create options—technologies that prove themselves in the market, mature without taxpayer risk, and are ready when defense or public missions need them.

If Congress rewrites SBIR rules to reward only Programs of Record transitions, these quiet commercial success stories will disappear, and so will the future ones hiding in today’s lab notebooks.

A Better Fix

Congress could demand portfolio-level accountability and create budget flexibility to achieve it. Require so-called SBIR Mills to show evidence that their SBIR portfolios generate commercial and government outcomes, measured by user engagement, follow-on investment, prototype use, and first adoption milestones.

That’s what high-performing programs like the Navy’s SBIR office already do. When program managers have resources and data to track impact, their portfolios outperform. Where they don’t, we get activity without results. Congress can bank that major win with a minor legislative fix to relax the spending cap on what it truly costs to run an effective innovation portfolio.

Keep the Seed Fund Working as Intended

SBIR was never meant to be a procurement program. It was meant to fund experiments—thousands of small, risky bets where both government and markets can find the next breakthrough.

Choking off that diversity in the name of compromise would be like pruning a tree by cutting off its roots.

As a nation, we shouldn’t reward conformity. We should reward learning, progress, and real-world proof, whether that happens inside a defense lab or in a private factory. That’s how America’s seed fund grows.

Congress should adopt Ernst-style accountability. Lifetime caps will discourage rent-seeking SBIR Mills. Yet if a compromise is needed, any reprieve using transition metrics must recognize the value of commercialization. When a company earns traction in private markets, we all win.

About the Author: Brian Miller

Brian Miller is SVP at BMNT, leading federal acquisition and go-to-market strategy across business development, product, and government affairs. He is a former national security advisor and professional staff member for the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

Image: tsingha25/shutterstock