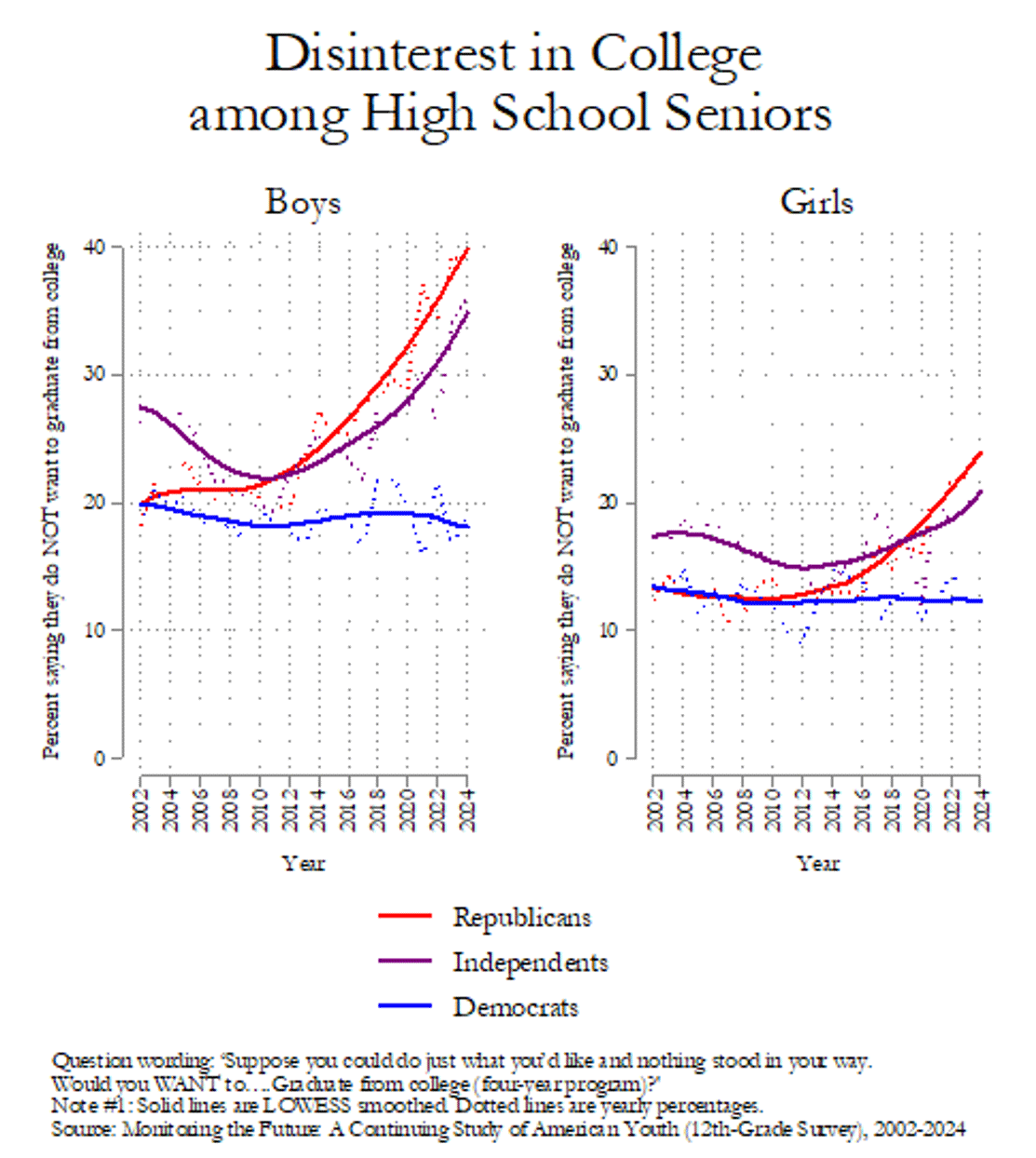

The clearest indicator of higher education’s decline is that fewer and fewer young people want to earn a bachelor’s degree. The share of high school seniors who say they do not want to graduate from college rose from 18 percent to 30 percent between 2011 and 2024, according to the Monitoring the Future survey.

Some argue that non-college career opportunities, high costs, or the Covid pandemic are responsible for young people’s declining enthusiasm. But there is another, deeper cause: over the past 15 years, universities have become more ideologically homogenous, more overtly activist, and more monomaniacally focused on power and identity.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

We see this reflected in the timing and ideological asymmetry of high school students’ declining interest in college. While the share of self-identified Democrats aspiring to graduate has remained unchanged over the past 15 years, disinterest in higher education among everyone else has skyrocketed. Since 2011, the percentage of high school seniors with no interest in a four-year degree has roughly doubled among Republican boys (20 percent to 39 percent), Republican girls (12 percent to 24 percent), and independent boys (19 percent to 36 percent).

The political composition of university faculty now skews heavily to the left. In 1995, the liberal-conservative ratio was roughly two-to-one. By 2010, the ratio was five-to-one.

The most recent data suggest even less ideological diversity. Data from 2019, for example, found that more than 60 percent of faculty were left-leaning, while only 10 percent were right-leaning. In 11 surveys conducted between July 2021 and August 2022, those calling themselves “far left” or “very liberal” (11.4 percent) outnumbered the entire right-of-center faculty combined (10.9 percent). Notably, one survey found that about 40 percent said labels like “radical,” “activist,” “Marxist,” or “socialist” described them at least moderately well.

Nor is the political homogeneity confined to faculty. More than 70 percent of college administrators and more than 60 percent of students now identify as liberal.

The scholarship produced by universities has shifted left as well. A study of 175 million abstracts from scholarly articles published between 1970 and 2020 found that “the prevalence in the academic literature of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse”—for example, racism, sexism, transphobia, Islamophobia, and fatphobia— “accelerated abruptly after 2010.” The research produced by universities is now far more focused on identity-based bias and discrimination than it was 15 years ago.

Instances of the “heckler’s veto”—efforts to silence speakers through noise, intimidation, or violence—have risen steadily since 2014, pausing only briefly during Covid. According to the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression’s Campus Deplatforming Database, the number of speakers targeted by “attempted” or “substantial” disruptions climbed from just three in 2021 to 79 in 2024.

The cumulative effect of these changes has been the evaporation of trust in higher education, particularly among conservatives. According to Gallup’s surveys, from 2015 to 2024, the percentage of Republicans expressing “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education fell from 55 percent to 20 percent.

Gallup’s data showed that 41 percent of those distrustful of higher education claimed colleges and universities were “too liberal,” trying to “brainwash” students or failing to encourage students to think for themselves. Similarly, in the 2024 American National Election Study pilot, nearly 60 percent of Americans—including 47 percent of liberals—said “most colleges have a liberal bias in what they teach students.” Exposure to clips of disruptive, speech-related protests also increases negativity toward higher education.

More importantly, the percentage of high school seniors in the Monitoring the Future survey who say that colleges and universities do a “good” or “very good” job for the country plummeted from roughly 80 percent in 2002 to about 40 percent in 2024. These negative perceptions are driving conservative students and their parents to look for alternatives to higher education.

This is bad news for conservatives, colleges, and the country. Universities remain, with some notable exceptions, one of the few proven strategies for upward social mobility. Moreover, a conservative exodus from colleges will leave corporations, media, academia, and government without the voices needed to argue for right-of-center approaches to public policy issues.

Conservatives must realize that not all colleges and universities are intellectual monocultures that prioritize ideological activism over academic rigor. As the 2025 City Journal College Rankings show, numerous schools uphold rigorous standards, encourage debate, and maintain a welcoming environment for ideological and intellectual diversity.

Many universities—including Penn State, the University of Alabama, Clemson, Furman University, Boston College, and Pepperdine University—have roughly equal numbers of conservative and liberal students. Claremont McKenna College, the University of Tulsa, Notre Dame, and others feature professors ranging across the political spectrum. Schools like the University of Florida, the University of Texas at Austin, Arizona State University, and the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill have programs dedicated to providing foundational education in the humanities and social sciences, organized around explicit commitments to civil discourse and education for citizenship.

At the same time, institutions of higher education must realize that it is in their interest not to alienate large swaths of potential enrollees. Facing the nation’s low birth rates, declining interest from international students, and increasingly conservative high school boys, colleges and universities cannot stay on their current course and remain fiscally solvent or socially relevant.

The schools can make three relatively easy interventions. First, they should adopt the Chicago Statement—the free speech policy produced by the University of Chicago’s Committee on Freedom of Expression. This would help rebuild confidence in universities as “truth seekers.” Second, they should address their faculty viewpoint diversity problem—for example, by eliminating mandatory DEI statements in faculty hiring. Finally, colleges and universities must heed the Kalven Report’s reminder that they are “the home and sponsor of critics,” not critics themselves.

Photo by Lance King/Getty Images

Source link