Last week, the New York Times released a six-episode podcast series called The Protocol. The series, a culmination of two years of investigative work by Times staff writer Azeen Ghorayshi, who writes on “the intersection of sex, gender and science,” explores the “big question” of how “the science and politics” of pediatric gender medicine “have gotten so entangled.” She hopes the podcast “can help challenge assumptions.”

The Protocol is worth listening to. Ghorayshi speaks with some of the biggest names in pediatric gender medicine, including the pioneer of the treatment protocol for youth in the Netherlands. Listeners will also hear the first-ever interview with “FG,” the Dutch female-to-male transitioner who was the first to receive puberty blockers for that purpose.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Where other left-of-center outlets deny the existence of problems in the field of youth gender medicine, The Protocol explains how the United States abandoned the guardrails of the Dutch Protocol—which included an age minimum of 12, at least six months of therapy, and a history of prepubertal gender incongruence—in favor of a child-led approach. Ghorayshi also fact-checks some activist narratives, explaining, for instance, why the oft-cited “1 percent regret rate” figure is not based on credible evidence.

The Protocol deserves credit for demonstrating that criticism of the American “gender-affirming” model of care need not be motivated by bias or anti-scientific attitudes. It leaves listeners with a strong impression that some American doctors have badly failed their patients. But the podcast’s strengths are overshadowed by its weaknesses. Here, I will discuss its treatment of the politics of gender medicine. In a follow-up, I will explore its examination of gender medicine itself.

All good stories need villains and heroes, and The Protocol tries to offer a good story. The bad guys include clinicians who practice the American version of the Dutch Protocol, represented by Johanna Olson-Kennedy of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; and Republicans, who seek to “ban the care.” The former group’s wrongdoing is derivative: the affirmers’ reckless practices, though perhaps well-intentioned, produce more cases of regret, which are then “weaponized” to gin up support for bans.

The good guys are the “cautious” gender clinicians—those following what Ghorayshi and the narrator, Austin Mitchell, call the “assessment-based approach.” This model, we are led to believe, proceeds slowly and tries to ascertain through clinical tools whether a minor who seeks transition would benefit from it. Representing this approach are Laura Edwards-Leeper, the founding psychologist of the first pediatric gender clinic in Boston, and Scott Leibowitz, co-lead author of the “Adolescents” chapter of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s latest “Standards of Care.”

The podcast’s unmistakable message is that Edwards-Leeper and Leibowitz offer a golden mean between the nefarious Republicans and the imprudent affirmers. Ghorayshi and Mitchell are eager for listeners to calibrate their moral intuitions around this middle ground. But this golden mean, as I’ll explain in my next article, is really a golden mean fallacy. The “assessment model” is every bit as dubious—scientifically and ethically—as the affirmative model, and arguably more so.

But back to politics.

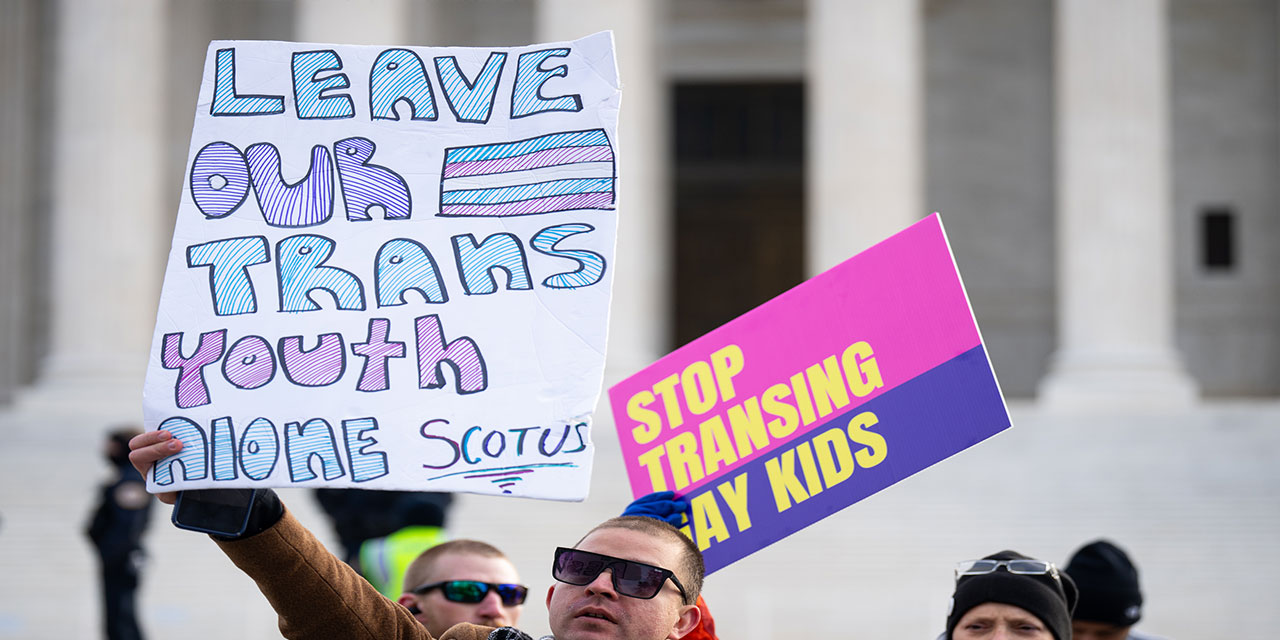

Twenty-seven states have now passed laws prohibiting the use of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries as treatments for gender dysphoria in minors. Later this month, the Supreme Court is expected to rule in United States v. Skrmetti whether these laws violate the Constitution, which the podcast’s release clearly anticipates. For the record, American age-restriction laws for medical transition are similar in their effect to the National Health Service’s decision to delist puberty blockers as the standard of care for pediatric gender medicine in the U.K.—a decision supported, it’s worth noting, by the left-wing Labour Party.

Language is very much part of the politics of pediatric gender medicine. The term “ban,” applied to these laws by their critics, is adopted reflexively in the podcast. It’s an odd choice, considering that we don’t usually talk about other age-restriction laws this way. No one calls age minimums for tattoos or alcohol “bans” on tattoos or alcohol.

The podcast also uses the term “gender-affirming care,” or “the care” for short, as if it were merely a neutral technical term, which, of course, it’s not. It’s a euphemism, and, like “child mutilation,” it reflects a value judgment.

Neutral language is available. “Pediatric medical transition” is one option; “sex-trait modification” is another. Neither implies anything about whether the interventions are justified.

Listeners could be forgiven for expecting that a podcast series focused on the intermingling of medicine and politics, and in which age-restriction laws play a central (if background) role in the narrative, would interview the Republican lawmakers who have written, sponsored, or defended these laws. But The Protocol includes exactly zero interviews with these lawmakers. Instead, it presents the Republican position as monolithic and almost exclusively through sound bites of Donald Trump—who likely knows close to nothing about this topic and in any case is a late-comer to the debate. When the question of Republican motives is finally broached in the last episode, it is answered by Scott Leibowitz, the WPATH-affiliated psychiatrist and a staunch opponent of age-restriction laws.

Let that sink in. In a podcast on medicine and politics, where age-restriction laws feature prominently as a theme, never once do listeners get to hear a justification for these laws from those who actually worked to pass them. Leibowitz dutifully asserts that age restriction laws are the product of a “very well-oiled financial machine . . . that is destined to eliminate trans care and, basically, trans rights and trans people from existence.”

Ghorayshi doesn’t push back. Among other things, she could have asked Leibowitz (or had host Mitchell explain) why the U.K. ban on puberty blockers, condemned by WPATH and at odds with Leibowitz’s approach, was endorsed by the Labour government. Is Labour bent on “eliminating trans people from existence?” Ghorayshi, in short, seems entirely incurious about the views of Republicans who have taken on this issue.

Having worked with some of these Republicans, I can attest that their depiction in The Protocol reflects a gross and highly partisan caricature. Have some Republicans engaged in this issue with mean-spiritedness and unconcern for medical science? Of course. Do those who care about medical science always get it right? Hardly. Is Trump’s rhetoric on this issue inflammatory and counterproductive? I believe it is.

But many Republicans at the state level—where most youth gender-medicine policy is made—have shown keen interest in the medical research, taken time out of their busy schedules to familiarize themselves with the framework of evidence-based medicine, and asked me questions like, “What’s going to happen to these kids once the law goes into effect” and, “What can we do to get medical associations to accurately incorporate the best evidence into their guidelines?” Some of these lawmakers are medical professionals. Some know the names of influential studies by heart and can recite their chief flaws. Some have read the Cass Review, or parts of it anyway.

Interestingly, Democrats, who prefer to “trust the experts,” often fail to show the same level of curiosity or command of the literature. It’s this (misplaced) trust that puts them at an intellectual disadvantage when confronting their Republican colleagues in committee hearings—a dynamic I have observed on more than one occasion.

At no point does Ghorayshi consider the possibility that Republicans moved to “ban the care” in response to a Wild West of unregulated medicine—where medical groups like the American Academy of Pediatrics misled the public, doctors misled parents, and Democrats refused to hold the profession accountable. The duty of government to regulate an industry, when that industry fails to regulate itself, used to be a core belief of American liberalism. The story of pediatric gender medicine in the United States is, in large part, one of the medical profession’s failure to self-regulate. That failure is a key part of the story of how medicine and politics became entangled, but The Protocol never mentions it.

Instead of fairly representing the diverse motives and opinions of GOP lawmakers, The Protocol serves up a Manichean tale. Republicans are an evil presence, always in the background of The Protocol’s developing story, providing a foil for the dramatic interplay of the characters whose motives and actions are of interest.

Democrats are absent from The Protocol as well. One might have expected Ghorayshi to ask Democratic lawmakers—like California state representative Scott Wiener, an architect of the “sanctuary state” movement for trans-identifying children seeking hormones—about, say, their deference to groups like WPATH. Or perhaps to interview Rachel Levine, the Biden administration’s assistant secretary for health—who, as Ghorayshi herself reported last year, pressured WPATH to eliminate age minimums for hormones and surgeries for political reasons.

Nada.

Some of the activist talking points that The Protocol challenges—like the claims about suicide or extremely low regret rates—have been repeated ad nauseum by Democratic lawmakers in legislative hearings and in media appearances. It would have been nice to hear The Protocol mention that, as well.

Unsurprisingly, Ghorayshi and Mitchell also fail to mention the dozen or more state-level Democrats who voted in favor of age-restriction laws. Would listeners not benefit from hearing why, in an age of intense party polarization, these Democrats risked their political careers to break party lines?

They could have interviewed Shawn Thierry, a former Democratic representative from Texas who gave an emotional speech on the statehouse floor explaining why she decided to put child welfare above “political expediency.”

Or they could have interviewed Jonah Wheeler, a young Democratic representative from New Hampshire, who voted to ban surgeries and puberty blockers as treatments for gender dysphoria for minors in his state. “Despite the fact that I am a liberal,” Wheeler said in a speech explaining his decision, “despite the fact that I believe in nondiscrimination for trans people, for gay people, for queer people and that I will fight until my very last day until they are recognized as human beings, the question before us is whether or not children under the age of 18 should be able to get these surgeries. And I, despite being a liberal who believes in those human rights, do not think that is the case.”

But they didn’t.

In The Protocol’s telling, the politics of gender medicine in the United States boils down to a single fact: Republicans want, for reasons we apparently needn’t understand beyond a gender clinician’s imputation of prejudice, to “ban the care.”

One can imagine a world in which Democrats and Republicans both recognize, perhaps for different reasons, that something has gone wrong in how gender-nonconforming children are treated by medical professionals. They could work together to launch inquiries, gather evidence, and advance bipartisan efforts to hold wrongdoers accountable and ensure optimal care for youth.

Sadly, that is not the world we live in. Not all Republican lawmakers care about evidence-based medicine, and some—though I don’t think it’s a majority or even a substantial minority—may harbor bad motives. But the truth is that even if Republicans didn’t take their bearings from medical science, their position is still far more aligned with medical science and basic principles of medical ethics than the Democrats’. Democrats appear to be beholden to “the groups”—nonprofits, foundations, and donors with views far to the left of the average American. How else to explain the phenomenon of Democratic lawmakers continuing to cite the widely discredited guidelines of WPATH—which most countries that practice pediatric gender medicine now recognize as untrustworthy, even dangerous—or the growing divergence of Democratic lawmakers from their own base on this issue? As The Protocol notes, 54 percent of Democratic voters now believe that doctors should not offer puberty blockers or hormone therapy as treatments for trans-identifying minors. A Gallup poll from a year ago found only 25 percent of Democrats supported a “ban” on “gender affirming care.”

Had The Protocol explored these issues even a little, listeners would have emerged with a more nuanced grasp of how “the science and politics have gotten so entangled.”

My view is that the state of gender medicine in the United States results from several key factors, including the decentralized nature of our health-care system and the weakness of our political parties, which leaves both susceptible to pressure groups and populist figures. When these and other dynamics converge with an inherently controversial medical protocol, politicized medicine is the predictable result. There’s a reason countries like Sweden and Finland have found it easier to commission evidence reviews and incorporate their findings into medical policy. America’s health-care system gives states significant authority over medical regulation, and its polarized political parties exert similar influence over regulatory agencies. Unfortunately, none of this is explored in The Protocol.

Some will say that podcasts are limited in time and scope, making it necessary to cut content, sometimes even when it’s important. While true, this is also an excuse. Given The Protocol’s own stated ambitions, its failure to explore the complexities of political opinion even at the most rudimentary level is disappointing, and a missed opportunity. I will defer my speculation as to why this choice was made for my next post, where I discuss The Protocol’s analysis of the medicine.

Photo: Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

Source link