The 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress—also known as the “Nation’s Report Card”—is now out. It shows 12th-graders’ performance slipping to a record low.

According to the report, one-third of seniors are reading at a below-basic level, and only 35 percent are proficient or above. In math, 45 percent are below basic, with just 22 percent meeting proficiency. The proportion of students at the 10th and 25th percentiles has fallen to historic lows, widening the gap between the highest-and lowest-achieving students and leaving many unprepared for life after high school.

The declines reflect the failures of more than a decade of educational policy—specifically, a retreat from expectations that began under the Common Core Standards and continued under the Every Student Succeeds Act.

Declines have not always been so predictable. Under the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act, passed in 2002, results were more stable. Reading scores remained 25 percent below-basic and 37 percent proficient, while math scores remained 33 percent below-basic and about 25 percent proficient. As Roberta Rubel Schaefer recently explained for City Journal, NCLB established rigorous, content-rich curriculum standards and tracked schools and students’ performance through regular testing, encouraging a culture of educational excellence.

After 2013, as states adopted the Common Core Standards and later, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) took effect in 2016, progress declined. Proficiency remained stagnant, while the number of students reading and doing basic math below the basic level increased.

12th Grade NAEP Results (2013–2024)

| Year | Reading: Below Basic | Reading Proficient or Above | Math Below Basic | Math Proficient or Above |

| 2013 | 25% | 37% | 35% | 26% |

| 2015 | 28% | 37% | 38% | 25% |

| 2019 | 30% | 37% | 39% | 24% |

| 2024 | 32% | 34% | 45% | 22% |

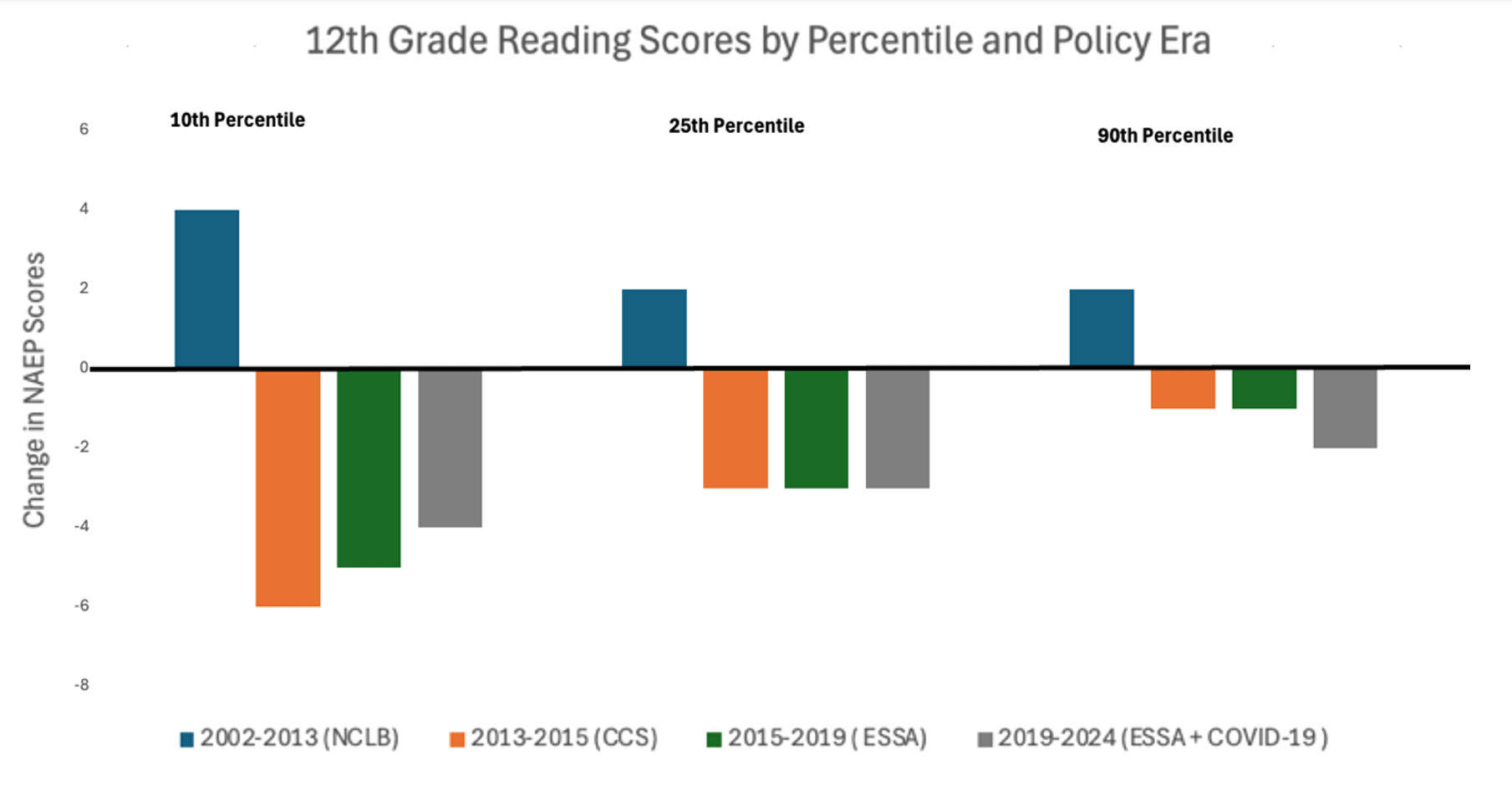

Focusing only on overall proficiency misses the deeper failure: the lowest-performing students fell back the worst once Common Core and ESSA took hold. Scores at the 10th and 25th percentiles decreased. Struggling students slipped further behind.

Under NCLB, the lowest-performing students gained 4 points in reading and 6 points in math. After 2013, these gains reversed, with a 6-point drop in reading and 3-point decrease in math after ESSA was implemented. Instead of closing gaps, the reforms widened them, leaving students already behind with the least chance of catching up.

The decline is even more evident when observing the Class of 2024 as a cohort. In 2015, when these students were fourth-graders, 36 percent were proficient in reading and 31 percent were below basic. By eighth grade in 2019, only 33 percent were proficient, and 28 percent were below basic. By their senior year, proficiency stood at 34 percent, with 32 percent of those students below basic. Students who struggled early never caught up; their deficits only widened.

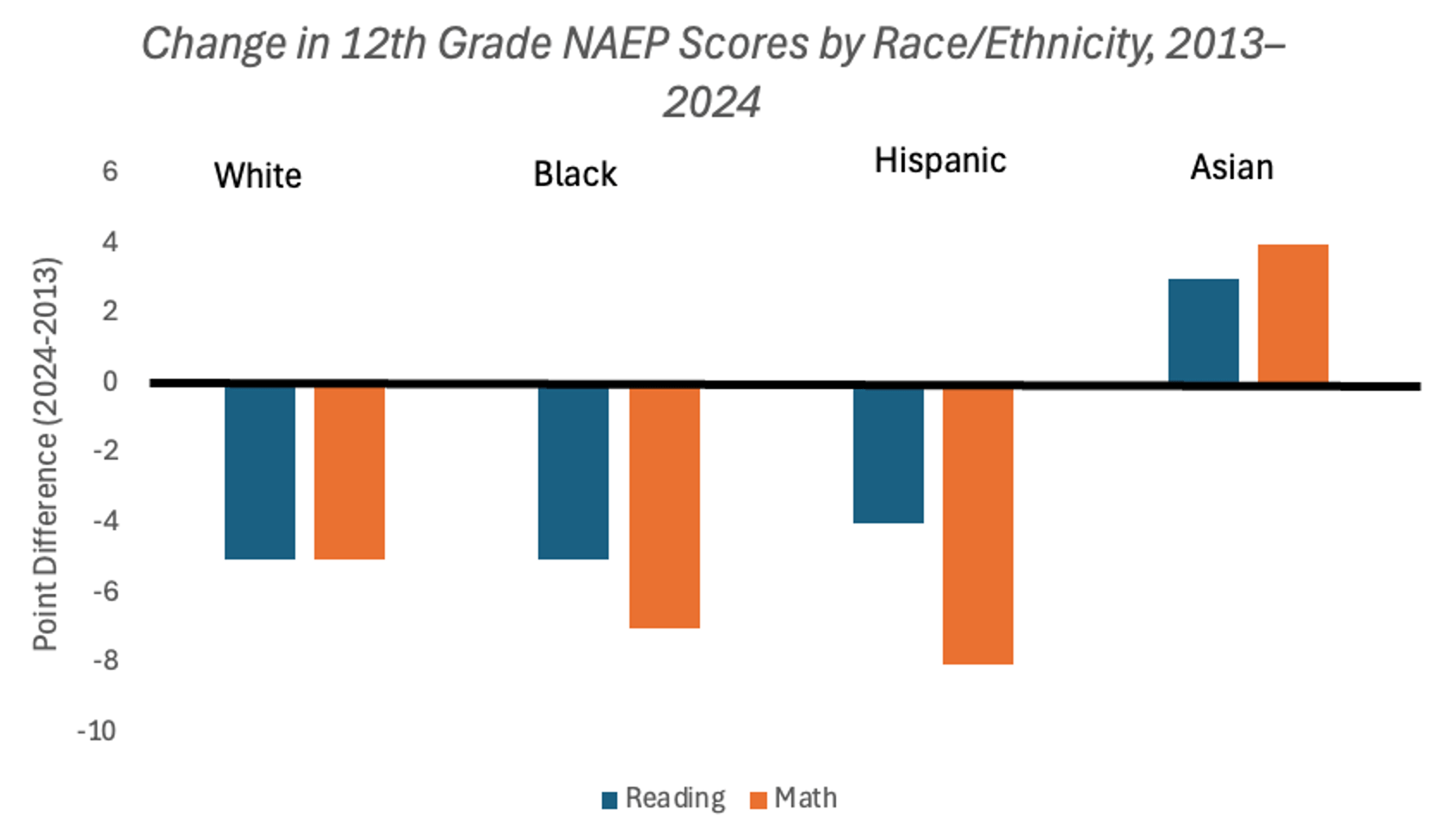

Deteriorating performance since 2013 shows up across almost every racial and ethnic group. White, black, and Hispanic students all showed declines in both reading and math. Hispanic students took the largest step backward in math—8 points. The only group to see gains was Asian students, who improved in both subjects.

The outcomes we’re seeing see now reflect a growing toleration of lackluster achievement. While NCLB was far from perfect, it held schools accountable. In 2011, the Obama administration granted states waivers from NCLB in exchange for their adopting college-readiness standards, primarily Common Core, that reduced accountability. In 2015, Congress formally replaced NCLB with ESSA, providing states with more flexibility. Academic progress collapsed as accountability weakened and instruction shifted in the wrong direction.

When ESSA formally replaced NCLB, it left states free to lower the bar and avoid consequences when students were not reaching proficiency. By the time Covid-19 disrupted classrooms, the nation was already in an academic crisis.

The federal era of school reform has proved unsuccessful. As control shifts back to the states, governors and legislatures urgently need to correct course.

First, bring back accountability. States need clear proficiency benchmarks and must enforce consequences when schools fail.

Second, fix the standards. Instead of starting with college and working backward, standards should be built from early grades up so that students can master the basics.

Third, states must track student progress over time and make these data public. Parents and the public deserve clear reporting on whether schools are narrowing academic gaps or students are falling further behind.

The Nation’s Report Card doesn’t just measure student progress; it measures the effectiveness of educational policies. For over a decade, these policies have failed our students, as the 12th-grade results for 2024 make clear. Unless states restore accountability, fix their standards, and ensure transparency, the senior class of 2024 will not be our last lost generation.

Photo: Rafa Fernandez Torres / Moment via Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).