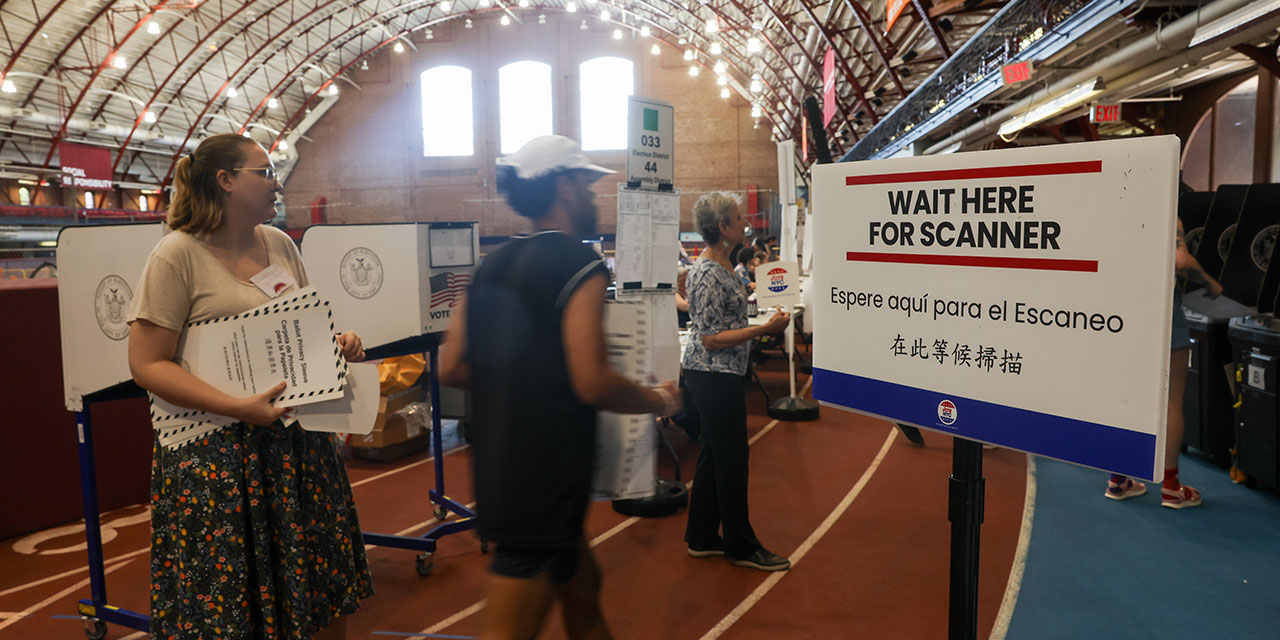

Last week, the chair of the New York City Charter Revision Commission (CRC) announced that the body would not submit to voters a proposal to reform the city’s local primaries. The plan ostensibly failed because the CRC lacked a “clear consensus” on how to proceed. But the Commission’s interim report, issued on July 1, contained an eminently workable proposal: using ranked-choice voting to select two winners in an election open to all candidates and registered voters, regardless of party registration, who would go on to a general-election runoff.

The real reason for the reform proposal’s demise is likely concerted opposition from the Working Families Party, Comptroller Brad Lander, and other leftist activists. These groups threatened to oppose the measure and even sue the CRC if it put the question to voters. In so doing, they have killed any foreseeable hope for primary reform in New York City.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Closed primaries in New York City’s local elections limit participation to registered party members. Democrats represent about 65 percent of the city electorate and enjoy a nearly six-to-one registration advantage over Republicans. The Democratic primary is thus both the most important election in the city and a race closed to nearly 2 million registered voters. Most local primaries are also low-turnout affairs; the June 24 primary saw the most votes cast in decades, but even so, only about 32 percent of eligible Democrats turned out.

A sliver of the total electorate can make a Democratic candidate the odds-on favorite to be mayor. Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani won the June 24 Democratic primary with about 573,000 final-round votes—56 percent of the Democrats who turned out, but only about 11 percent of all registered New Yorkers.

The closed primary proved favorable terrain for Mamdani’s campaign, as his army of volunteers did not need to reach non-Democratic voters to secure his victory. Republicans did not hold a mayoral primary, opting instead to crown Guardian Angels founder Curtis Sliwa for the party’s guaranteed general-election line.

In a series of hearings that took place beginning this past winter, the CRC received input on ways to open the primaries. (I testified in-person twice and sent extensive written comments.) Though these proposals varied, reform advocates and organizations broadly agreed that closed primaries suppressed non-Democratic voters, limited political competition, and motivated candidates and elected officials to appeal to an unrepresentative electorate. Unaffiliated voters took to hearings to vent their frustration about their inability to participate in the city’s most important election. Over the spring, momentum for primary reform grew.

The CRC’s interim report suggested a proposal for a “top-two” primary, in which all candidates would appear in a ranked-choice primary open to all voters and all candidates, regardless of party. The ranked-choice mechanism would successively eliminate the bottom candidate, redistributing that candidate’s ballots to voters’ next-ranked choices, until only two candidates remain. Those two—and only those two—would proceed to the general election.

Manhattan Institute polling reveals that New Yorkers from across the political spectrum want to change the city’s electoral structure. A 37 percent plurality of those polled in January 2025 preferred a top-two primary over closed- and open-primary alternatives. Among Democrats, support is even higher, at 38 percent.

Yet Mamdani’s victory in an election marked by a significant uptick in turnout and enthusiasm has given far-left activists and groups reasons to oppose the CRC’s proposed primary changes. At the first post-primary CRC hearing on July 7, Comptroller Brad Lander said, “Zoran Mamdani won, and he’ll be the Democratic nominee for mayor in November. That’s democracy as we have practiced it here for generations, but now it appears some people for whom the race didn’t go the way they wanted want to change the rules.”

Jasmine Gripper, co-director of the New York State Working Families Party (WFP), threatened to sue the CRC at the hearing if it put primary reform on the ballot. She also complained that opening primaries—and expanding turnout—would dilute the WFP’s influence by raising the cost of influencing voters.

“We are influencing a Democratic primary. We are only talking to people who are registered Democrats,” Gripper said. “When you now make that open to everyone, it makes it nearly impossible to do any targeting, and it costs a lot more to send out mailers and to do phones and to do text.”

In other words, making it possible for more New Yorkers to vote in a primary would make it harder for the WFP to secure a victory for their preferred Democrats. The party endorsed a slate of four mayoral candidates in the recent Democratic primary, with Mamdani as their first choice. Gripper didn’t care that she and her fellow WFP voters could not vote for those candidates; she instead contended that voting in the primary “is just one way in which you can participate.” Door-knocking and talking to voters were other ways she could “feel empowered” in her choice to be a WFP member without a vote.

It’s ironic that a state party that had previously committed to “the end of voter disenfranchisement and the strengthening of our democracy” is now fighting to exclude non-Democrats—including WFP-registered voters—from the city’s most consequential election. With the prospect of gaining power before them, the pro-status quo Left is gatekeeping the vote rather than expanding local democracy. Unaffiliated voters are out of luck.

Wednesday’s announcement blamed the lack of consensus among civic leaders about what reform should look like. But electoral reform comes in many varieties—it’s unrealistic to expect anything resembling a consensus on a single model. What should have mattered was whether the top-two proposal presented a better set of tradeoffs than closed primaries, so that voters could decide which system they want.

The demise of primary reform raises the stakes for November’s mayoral election. A top-two electoral system would have encouraged future elected officials to appeal to a broader, more representative electorate, both in office and on future campaign trails. That Mamdani’s supporters oppose primary reform also signals that, if he wins in November, he probably would not convene another CRC to address primary reform. And even if another candidate wins, the Left will strangle attempts at reform in the cradle.

For the foreseeable future, unfortunately, New York is stuck with closed primaries.

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link