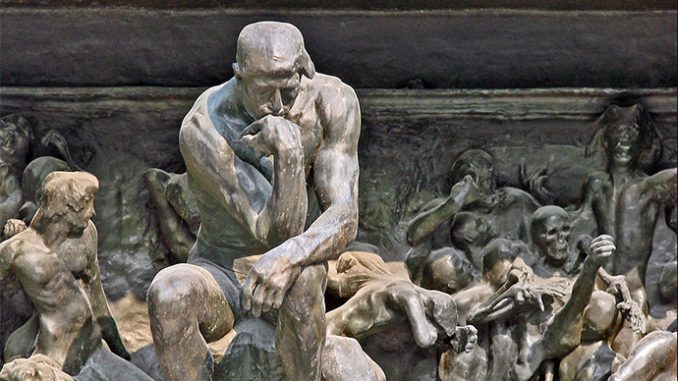

I swear to you that to think too much is a disease, a real, actual disease.—Fyodor Dostoevsky

Years ago, in a pique of weight lifting enthusiasm, I stumbled across an intriguing interview in Muscle and Fitness Magazine. A bodybuilder, whose name is lost in the murky mists of my memory, meticulously unfolded his elaborate program of “cutting” for competition. Apparently, in the final days and hours before posing, these world-class competitors do all they can to shed water in order to qualify for a particular weight class and effect a strikingly chiseled—literally, marble-esque—appearance. His approach involved donning multiple layers of clothing, sprinting up and down a local fire escape, consuming various last-minute supplements, and popping diuretics.

Clearly, he was an articulate man describing his plans in enthusiastic detail. But when complimented on his intensely analytical approach to success, he answered darkly, “An analytical mind is a heaven and a hell in itself.” Sometimes, he admitted, he just couldn’t turn it off.

If there is anything I encounter again and again in my medical practice, it is people’s tendency to overthink. We all do it. When people worry, they are prone to magnifying small problems into big ones. They create deadly syndromes out of innocuous, disparate symptoms. Oftentimes, the more they think about it, the more pronounced the symptoms become. And they think about it a lot. Likewise, when the exam proves to be normal and the workup reassuring, their mind settles down, and the symptoms dissipate into the ether. Millions of patients appropriately go to the Emergency Room with chest pain, and they leave with a normal evaluation and a pain that soon mysteriously goes away. To be sure, the symptoms are real and frightening, but the overthinking mind-body connection creates an undeniable muddle.

Now, don’t get me wrong: thinking is good. After assembling and analyzing facts, we tap into our experience and intuition, common sense, and wisdom in order to navigate our way through the vexing problems of life. Again, thinking is good. But overthinking is not. It warps our sense of “what is.” It perseverates when we should let go. It fosters scrupulosity when we should consider the bigger picture. It heats up when we should cool down. And it often devolves into a vicious cycle from which it becomes difficult to emerge. Overthinking people become, implacably, stuck in their heads. A fellow physician and good friend frequently tells these patients, “There’s no extra credit for worrying.” Furthermore, he adjusts Socrates’ dictum, saying, “The OVERexamined life is not worth living.”

Maybe, some people reason, the solution to overthinking is to suppress our pesky emotions, blunt our all-too-human quirks and idiosyncrasies, and strive for cool, sterile logic. Perhaps if we operate like that Vulcan genius, Spock, we will solve all of these vexing and interminable problems. Perhaps, if we were less human and more like computers, we would emerge from the haze of wasteful overthinking.

Bah.

I always laugh at the breathless comparisons modern thinkers make between human beings and computers. To become more machine-like is their perennial solution. But this naïve contrast achieves three bad things: it forever denigrates people for not being as fast, efficient, or logical as computers; it erroneously presumes that human beings are inherently computer-like (with deficiencies, of course) in the way that we think; and it seems wistfully aspirational, as if becoming a computer is the gold-standard of human enlightenment.

But this is all nonsense. The difference between a human being and a computer is exemplified in the stark difference between Han Solo and C3PO. Who, really, do you want running your mission?

Human beings are blessed and cursed with inscrutables such as emotions and instincts, epiphanies and blind spots, biases and breakthroughs that confound the scientist’s algorithm. The romantic poet John Keats expanded on this blurring of lines between thinking and sensing in his description of “negative capability.” Great thinkers, he wrote, are “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” This, we know, comports with our own experience. We are a curious, ineffable amalgam of thought and feeling, sense and nonsense. When a colleague asserted that man is a rational animal, acclaimed historian Jacques Barzun stopped him short, “No—capable of reason.”

But the answer to overthinking—the hell of the analytical mind, as the aforementioned bodybuilder called it—is not to become less human, but to aspire to become a more refined human. With a sensible recognition of our pathological tendencies, a reasonable discipline that curbs our worst fears, and a winsome acceptance of the bad that invariably comes along with the good, we can come out aright.

There is a story of an old man having a conversation with his grandson. “Inside of me, there is a terrible fight underway—a fight between two wolves,” he explained. “The Dark Wolf embodies all that is evil—envy, greed, regret, sorrow, anger, and dishonesty. The Light Wolf embodies all that is good—generosity, love, hope, contentment, and kindness. It is a fight that occurs inside you too, and everyone living on earth.” Unnerved, the boy earnestly asks his grandfather, “Which wolf will win?” His grandfather paused and looked him straight in the eye and replied: “The one you feed.”

The Dark Wolf could just as well be comprised of the darkness of overthinking, while the Light Wolf embodies the cheer of clear thinking. The question is, “Which one will you feed?”

To be sure, it is good to think.

But that bodybuilder was right: it is hell to overthink.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.