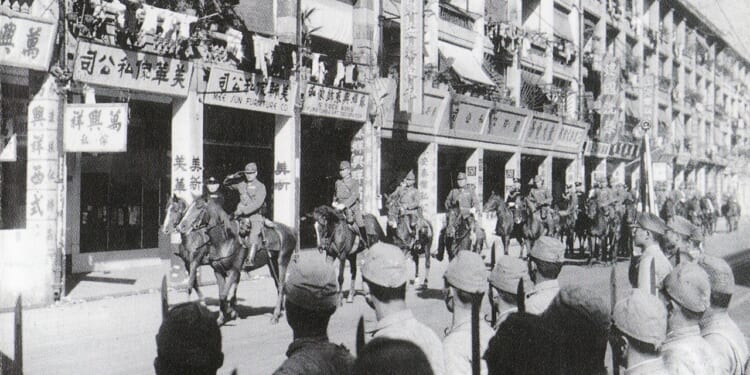

The defenders of Hong Kong, tens of thousands of miles from any conceivable relief force, surrendered the territory to Imperial Japan on December 25, 1941.

Everyone remembers the Japanese Imperial Navy’s surprise attack upon the United States Navy base at Pearl Harbor and the United States Army Air Corps’ facilities in Hawaii. But fewer Americans know that the attack on Pearl Harbor came as only one part of Japan’s broader attack on the Western Allies—and that in the same hours as Japanese planes bombed Hawaii, the forces of the Empire of Japan launched a nearly simultaneous set of offensives against key targets throughout the Pacific region.

Japan’s Grand Offensive in 1941-42

Tokyo’s grand strategy was to knock the American military juggernaut out in one fell swoop—Pearl Harbor—and then, assured that the US Navy could not interfere, systematically pick apart the far weaker American, British, and other Allied troops stationed in territories closer to Japan.

In the hours after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese attacked the Philippines. They struck at Midway. Within months, they had stormed into Singapore, which capitulated in what Winston Churchill described as the worst disaster in British military history. And Japanese troops also went hard against Hong Kong.

By December 1941, Japan had been at war with China for more than four years. Japan had occupied vast swaths of Chinese territory, and battle-hardened Japanese troops were primed for action against the sparse defenders that the British, Canadians, Americans, and other European powers had left behind to defend their various interests in the region.

After all, for the British and other Europeans, the real action for them was back in Europe—and that was the theater they understandably prioritized. They left the bulk of the defense of their interests to the Americans.

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese attacked Hong Kong as part of their early Pacific offensive. The defenders—a combination of British, Indian, Hong Kong volunteers, and Canadian units—were slammed by the Japanese invaders.

Having arrived in October 1941, nearly 2,000 Canadian soldiers from the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers were deployed by Ottawa to reinforce the British garrison defending the Crown Colony of Hong Kong. These troops, known as “C Force,” entered Hong Kong to reinforce their British cousins on November 16, 1941.

Because their arrival was merely weeks before the Japanese launched their brutal assault on Hong Kong, the Canadian force had little time to train. Fighting dragged on through December 23 and December 24, with the Canadian garrison struggling to hold their positions defending Hong Kong.

On Christmas 1941, Hong Kong Surrendered to the Japanese

By Christmas Day, the situation became untenable. Little ammunition, lack of food, and dwindling supplies—with any prospect of relief tens of thousands of miles away—the Allies defending Hong Kong surrendered to the Imperial Japanese Army. The fall of Hong Kong was referred to as “Black Christmas,” as it marked a horrific period of bloodshed and tyranny imposed by Tokyo.

The Battle of Hong Kong was the first major land combat that Canadian soldiers participated in during World War II. Those 2,000 Canadian troops, despite being unprepared for the ferocity of the Japanese attack, fought bravely for days with limited supplies and no hope of relief.

Of the approximately 1,975 Canadians who went to Hong Kong, 290 were killed in action. Another 493 were wounded. Hundreds more were taken prisoner by the Japanese after the surrender.

Unbeknownst to the surrendering soldiers, the Japanese had no intent of following the Geneva Conventions safeguarding the treatment of prisoners of war. Many who survived that awful Black Christmas later died painful deaths in the notoriously brutal Japanese prisoner of war (POW) camps, due to starvation, disease, and torture suffered at the hands of their captors.

The Battle of Hong Kong is widely considered to be a sobering chapter in Canadian and Commonwealth military history. It is significant because it began Canada’s first major combat in the war. It is also important because of the severe sacrifices and brutal captivity that resulted from Black Christmas.

December 25, 1941, was a truly Black Christmas. It was a day in which no mercy was granted to the gallant and overmatched Canadian defenders of Hong Kong—whom were defeated by an enemy that did not even share the same sympathies toward the Christmas Holiday that the Canadians did, meaning no mercy of the sort that occasionally displayed itself on Christmas in the European Theater could hope to have been experienced by the Canadians in Hong Kong.

About the Author: Brandon J. Weichert

Brandon J. Weichert is a senior national security editor at The National Interest. Recently, Weichert became the host of The National Security Hour on America Outloud News and iHeartRadio, where he discusses national security policy every Wednesday at 8pm Eastern. Weichert hosts a companion book talk series on Rumble entitled “National Security Talk.” He is also a contributor at Popular Mechanics and has consulted regularly with various government institutions and private organizations on geopolitical issues. Weichert’s writings have appeared in multiple publications, including The Washington Times, National Review, The American Spectator, MSN, and the Asia Times. His books include Winning Space: How America Remains a Superpower, Biohacked: China’s Race to Control Life, and The Shadow War: Iran’s Quest for Supremacy. His newest book, A Disaster of Our Own Making: How the West Lost Ukraine is available for purchase wherever books are sold. He can be followed via Twitter @WeTheBrandon.

Image: Wikimedia Commons.