In a world increasingly shaped by US-China energy bipolarity, the EU must reduce its strategic vulnerability to both fossil-fuel exporters and clean-technology powers by recalibrating its regulatory approach, reimagining energy security around resilience and adaptability, accelerating electrification, and avoiding new forms of dependence on any single power.

The world is entering a new era of energy bipolarity. On one side, fossil-fuel exporters (“PetroStates”) are seeking to consolidate their power through higher oil and gas exports. On the other hand, clean-technology powers (“ElectroStates”) are accelerating the electrification of their energy systems while strengthening their stronghold on all the technologies that enable it. This conceptual dichotomy—which we first outlined in our earlier piece, “PetroStates and ElectroStates in a World Divided by Fossil Fuels and Clean Energy”—has since become visible in an energy order increasingly shaped by the tension between these two models.

Yet this energy bipolarity sits within geopolitical bipolarity, defined by the growing rivalry between the United States and China. Washington remains the central node of the global fossil-fuel economy: it is the world’s largest oil and gas producer, a financial hegemon, and now the largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporter. Beijing, by contrast, anchors the clean-technology superstructure: it controls over 70 percent of global solar manufacturing and battery cell production capacity, and dominates the processing of most critical minerals essential for electrification.

Thus, while PetroStates and ElectroStates shape global energy flows, the gravitational forces that structure the system emanate from the two superpowers. The United States and China are not simply large participants in the energy market—they are order-shaping poles; the United States through financial power, sanctions, LNG export dominance, and its security footprint, and China increasingly through manufacturing scale, supply-chain control, and the technical standards in clean-energy industries.

In this tightening bipolar landscape, Europe occupies a deeply uncomfortable middle ground—highly dependent on both blocs, yet fully aligned with neither. The region aspires to become an ElectroState, consistent with its Net Zero ambitions, but it remains heavily reliant on Chinese clean-technology supply chains and continues to import large volumes of fossil fuels. Consequently, Europe’s vulnerabilities are no longer merely commercial or technological; they are becoming structural features of a system shaped by two competing powers.

Europe, therefore, enters this new era facing its most strategically constrained energy environment in modern history. This raises a fundamental question: can the Continent transform itself from a vulnerable importer to a more resilient and more autonomous actor?

Europe’s Current Situation: From Dual Dependency to “Asymmetric Embeddedness”

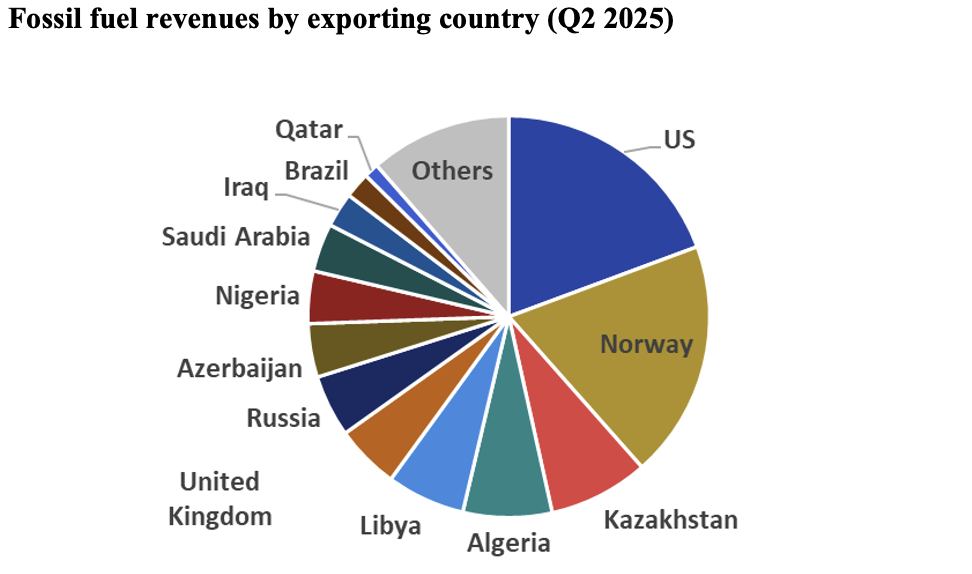

Despite the European Union’s (EU) ambition to reach Net Zero by 2050, fossil fuels still accounted for 73 percent of its primary energy consumption in 2024. Compounding this challenge, the EU—a very small oil and gas producer—is highly dependent on fossil fuel imports, especially for oil and gas (over 95 percent and around 90 percent, respectively). Moreover, Europe is not merely dependent on imports—it is embedded in asymmetric energy relationships that reflect US-China rivalry. Its dependency profile is no longer about volumes alone; it is about whose strategic interests those dependencies ultimately serve.

EU countries may be close to eliminating their dependency on Russian gas, but they have now traded this dependency for another. Around 45 percent of the EU’s gas imports in the first eleven months of 2025 came in the form of LNG, more than half of which originated from the United States. This dependence is structurally different from the past: whereas Russia leveraged pipelines, the United States leverages a combination of market power and broader geopolitical expectations. The Turnberry trade deal illustrates how the EU has become vulnerable to coercion from a partner that initially posed as a savior, but now expects Europe to accept a long-term dependency, while pushing it to diverge from its decarbonization ambitions.

Still, Europe has made progress in decarbonizing its power mix: in 2024, around three-quarters of EU power generation came from renewables, hydro, and nuclear. Yet the EU’s overall electrification rate stagnated at around 22 to 23 percent over the past decade, while China’s surged to around 29 percent as of 2024.

Europe seeks to reduce its dependency on fossil fuels through faster decarbonization. However, in doing so, it has also become crucially dependent on Chinese clean technologies: electric vehicles (EVs), solar panels, wind components, and batteries. Its exposure is particularly acute in critical raw materials, as it relies on a handful of suppliers, especially China. Export controlsannounced in April and October 2025 by China heightened concerns over this vulnerability and reminded policymakers that clean-tech dependence can be weaponized as effectively as fossil-fuel dependence. In response, the region adopted the RESourceEU Action Plan in December 2025, aiming to reduce dependency on Chinese supply chains for critical raw materials, support domestic mining and recycling projects, and start stockpiling in 2026.

Europe Is a Market and a Battleground

Europe faces a strategic dilemma rooted in its structural realities. The EU has no significant hydrocarbon resources to credibly position itself as a PetroState. Nor does it command large-scale ElectroTech manufacturing capacity that would allow it to become an ElectroState in the Chinese sense. What Europe does have—and what both PetroStates and ElectroStates covet—is a premium consumer market of more than 450 million people.

Yet market size does not necessarily translate into market power, especially when the importing region attempts to impose rules and regulations that exporters are not keen to accept. The EU’s fossil fuels import bill amounted to around €370 billion in 2024. Although it fell by 6 percent in the first half of 2025, Europe has repeatedly shown its vulnerability to external shocks: in 2022, this import bill surged to almost €700 billion. The German concept of Wandel durch Handel (change through trade) revealed its limitations in 2022 as Russia cut gas supplies to many EU countries, including its long-standing trade partner—Germany. The idea that economic interdependence alone could guarantee stability now appears dangerously naïve.

By becoming increasingly dependent on LNG, Europe now finds itself facing trade partners—most notably the United States and Qatar—that are joining forces to oppose the EU’s sustainability directive. Meanwhile, the United States has repeatedly urged Europe to adjust its methane regulation out of concern that these rules could impact US LNG exports, an issue that the EU is still working to address.

Despite these tensions, Europe will remain an important market for US LNG, with more than half of US LNG exported to the EU (and around two-thirds to Europe as a whole) in 2025. This is amplified by the fact that the Chinese LNG market remains effectively closed. With US LNG exports expected to exceed 300 billion cubic meters per year (bcm/year) in the early 2030s, US LNG exporters would struggle to place these volumes elsewhere if both markets were inaccessible.

The EU is also a key market for China’s clean technologies, accounting for well over a quarter of China’s clean-tech exports (over $5 billion per month in 2025). China’s dominance in these sectors is also coupled with significant overcapacity, as domestic demand cannot absorb the full scale of production. This has squeezed margins and raised profitability concerns for many Chinese manufacturers. This technology imbalance is compounded by the widening trade imbalance between the EU and China, with the bloc’s trade deficit approaching $300 billion in 2025—a level deemed unsustainable by European leaders. Europe’s role as a stabilizing outlet for Chinese overcapacity gives it latent leverage, but only if used deliberately.

In other words, Europe functions as a pressure valve for both poles—absorbing volumes, enabling profitability, and with EU regulations shaping which technologies and practices can compete globally. This gives Europe latent power, but only if managed strategically.

The old saying captures the structural imbalance well: “US innovates, China replicates, and the EU regulates.” But Europe’s reliance on regulation as its primary geopolitical instrument carries a built-in paradox. Regulation gives the EU influence—yet, if mis-calibrated, it can increase strategic vulnerability rather than reduce it. The recent tensions around the EU sustainability directive illustrate this clearly: rules designed to advance climate objectives ended up exposing Europe to pressure from key suppliers. Regulation meant to protect Europe’s interests has inadvertently amplified its dependence.

Thus, Europe is not just a market—it is an arena in which external powers compete for influence and where European regulatory choices can shift the balance of that competition, sometimes in unintended ways. The challenge for the EU is not to abandon regulation, but to deploy it with greater strategic awareness of its asymmetric dependencies and the reactions of both poles.

Strategic Response One: Energy Efficiency as Strategic Exposure Reduction

In a world where Europe has limited control over supply, its most reliable source of strategic autonomy lies in reducing final energy demand—using energy efficiency as a tool of strategic exposure reduction rather than merely a component of climate policy. Yet, despite being an obvious solution, energy efficiency still attracts limited political enthusiasm. The target agreed by 2030 (a 11.7 percent reduction compared with the projections of the EU’s 2020 reference scenario, or 763 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) is less ambitious than the EU Parliament’s proposal (14.5 percent or 740 Mtoe). Although EU countries appear broadly on track to reach the agreed target as of 2024, this progress may partly reflect the recent loss of industrial activity due to high energy prices, which was neither a desired nor intentional outcome.

Buildings are a key sector, accounting for around 40 percent of the EU final energy consumption (with 39 percent of space heating relying on gas). Although the solutions are well known, improving buildings’ energy consumption is often perceived by citizens as too costly, too complex (especially when it comes to accessing financial support), partial (for instance, replacing heating systems without improving insulation), and confusing, as regulations frequently change. Renovation projects are even more complex in apartment blocks, given the number of stakeholders to convince. Yet, building renovation and insulation deliver clear benefits: they support domestic employment, reduce o energy consumption, lower citizens’ energy bills, and often improve living comfort.

Europe’s industry, accounting for around a quarter of the EU’s final energy demand, is facing high energy costs, which the Draghi report has clearly identified as a major hurdle to competitiveness. Germany has already decided to lower electricity prices for energy-intensive industries, but such measures come at a cost, which more debt-constrained EU countries may be unable to bear. Both PetroStates and ElectroStates are well-positioned to take advantage of Europe’s precarious industrial position to strengthen their own industries: PetroStates continue to rely on abundant, low-cost fossil fuels for domestic use, while the Chinese ElectroState benefits from cheaper energy and integrated clean-technology supply chains. In particular, Europe’s defense sector needs to be strengthened and its resilience improved in terms of energy use and supply chain dependency.

Europe cannot eliminate external dependencies; it can, however, reduce the value of those dependencies to external actors.

Strategic Response Two: Secure Electrification Through Trusted Technology Alliances

Europe’s second strategic pathway builds upon the Green Deal concept: reducing Europe’s exposure to commodity volatility and supply coercion through electrification. Catavento underscores that electrification is the single most effective structural lever available to reduce long-term fossil-fuel exposure. This shift moves Europe closer to the ElectroState model, but electrification strengthens Europe only if the technologies that enable it do not become new vectors of dependence.

At the core of this strategy is electrifying end-use sectors. Electrified transport, widespread deployment of heat pumps, and increased use of electric technologies in industrial processes directly reduce exposure to the volatility, concentration, and geopolitical leverage associated with hydrocarbons. Done well, electrification transforms Europe from an importer dependent on external fuels into a region whose energy needs are increasingly met by domestic generation and regional grids. Electrification is not merely a climate ambition—it is a structural rebalancing of where strategic risk sits in Europe’s energy system.

Yet the transition from intent to implementation remains uneven. Several member states face political fatigue, uneven cost burdens, and fragmented regulatory timelines. Permitting remains slow, infrastructure deployment is irregular, and consumer acceptance is inconsistent across sectors. These gaps risk slowing or diluting the transition precisely at a moment when global energy competition is accelerating. Where China accelerates, and the United States subsidizes, Europe hesitates—and hesitation in a bipolar system carries strategic costs.

Moreover, in a US-China bipolar environment, electrification is not geopolitically neutral. The technologies required—from power electronics to digital control layers—are integral to superpower competition. Both Washington and Beijing aim to shape European technology choices, supply chains, and standards to reinforce their own strategic positions. If Europe accelerates electrification without strengthening its own technological and industrial capabilities, it risks trading fossil dependence for technological dependence, rather than gaining autonomy. For example, Europe’s dependence on Chinese solar inverters is increasingly considered a strategic risk. This concern is reinforced by cybersecurity assessments from the German Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) and the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), both of which identify inverter and power-electronics dependence—particularly on Chinese suppliers—as an emerging critical risk. Therefore, secure electrification requires not only deploying more electric technologies but ensuring that Europe controls—either alone or with trusted partners—the critical components and governance layers on which these technologies depend.

To make secure electrification meaningful in practice, three operational shifts are required.

- First, electrification policies must be paired with deliberate technology diversification. This means ensuring that heat pumps, EV drivetrains, grid inverters, and smart-metering systems are sourced from multiple trusted suppliers, not from a single dominant ecosystem. Electrification becomes a strategic gain only if the EU avoids technological lock-in – particularly in software, data governance, and critical electronics.

- Second, the EU needs to secure capacity in a limited set of strategic components, not the whole value chain. Europe does not need to replicate large-scale manufacturing of mass-market solar panels or basic battery cells. But it does need credible footholds in segments where vulnerabilities would undermine system resilience: power electronics, grid-management software, specialized industrial batteries, and components for charging infrastructure. Strategic realism is about identifying exactly which pieces of the chain Europe cannot afford to outsource entirely. A targeted industrial base yields far greater resilience than an expansive but shallow one. The EU must control the critical nodes of the energy system. These include inverter operating systems, protection relays, grid-control software, and the digital interfaces that determine system behavior. These components can be hacked or manipulated remotely by the supplier, making control over them central to sovereignty.

- Third, Europe must shape the standards governing interoperability, cybersecurity, and data governance. If European norms define how clean-energy systems must operate, suppliers must adapt to European rules—not the other way around. However, recent experience shows that Europe’s regulatory power is not without limits: when regulation is misaligned with geopolitical realities or concentrated supplier structures, it can backfire. The debates around the sustainability directive and the pushback on EU methane regulations illustrate how even well-intentioned regulations can trigger resistance from key partners, raise compliance costs, or inadvertently weaken Europe’s bargaining position. Effective standard-setting therefore requires not only technical ambition but geopolitical calibration—ensuring that rules reinforce, rather than undermine, Europe’s strategic autonomy.

These three shifts cannot be achieved by Europe alone. They require alliances capable of providing both technological trust and sufficient industrial scale.

If Europe is to lean further into electrification, it must regain strategic control over the technologies that make electrification possible. CleanTech is no longer just about hardware; it is increasingly defined by software, data architecture, cybersecurity, and system standards. These layers determine who ultimately controls the functioning of energy systems—and who can influence, disrupt, or manipulate them. In a world shaped by US-China technological rivalry, leaving these layers externally determined would undermine the very autonomy Europe seeks to build. In practice, this means Europe now competes not only for materials and components, but for the governance of the digital spine of its future energy system.

This is where a coalition of technologically aligned partners becomes essential. The “Good Guys Alliance” is not a third pole in the traditional sense, but a functional and counter-balancing pole: a coalition capable of anchoring secure clean-tech supply chains, harmonizing standards, and providing scale in system-critical technologies. In the attempt to re-shore or friend-shore green supply chains, Europe cannot out-subsidize the United States or out-scale China, but it can pursue targeted tech sovereignty in domains where loss of control would translate into strategic vulnerability. This includes power electronics, grid-management software, digital protection systems, advanced manufacturing components, and the governance of industrial data. These are not mass-market commodities; they are the “control points” of the energy system—and therefore the elements Europe must anchor domestically or within trusted alliances.

A “Good Guys Alliance” doesn’t need to be a formal pact; in practice, it means deepening operational cooperation with trusted suppliers such as Japan, Korea, Canada, Australia, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom (UK). These states share similar constraints—limited scale relative to China and limited fiscal firepower relative to the United States—but also share incentives to maintain open, rules-based, reliable technology ecosystems. Coordinated standards, reciprocal market access for strategic components, joint research and development (R&D) programs, and shared certification frameworks can collectively reduce dependence on any single external pole. Such cooperation allows Europe to borrow scale without surrendering sovereignty.

For Europe, tech sovereignty does not require building full domestic value chains. It requires three disciplined choices: controlling critical nodes, shaping system standards, and partnering where scale is impossible.

Secure electrification, therefore, rests on two pillars: targeted European capacity in system-critical technologies and alliances that provide the scale and trust needed to sustain them. Only by combining both can Europe avoid replacing fossil dependence with technological dependence—and turn electrification into a genuine engine of strategic autonomy.

In a bipolar world, this is the only pragmatic path between over-dependence and unrealistic self-sufficiency. Europe’s goal is not isolation from the superpowers, but insulation from their coercion.

Strategic Response Three: AdapTech and Energy Security Reimagined

Europe’s third strategic lever is to rethink energy security not as diversification of suppliers, but as redesign of the system itself. Traditional energy security was built around large assets—pipelines, LNG terminals, and centralized power plants—that delivered economies of scale but also created highly visible, highly coercible vulnerabilities. The experience of Ukraine demonstrated that such systems are easy to disrupt—the destruction of the Trypilska thermal power plant, the collapse of the Kakhovka hydropower dam, and even the sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipelines illustrate how large, centralized assets can become single points of failure. Resilience today requires systems that are modular, distributed, and intelligent. System architecture, not fuel origin, increasingly determines vulnerability.

By integrating distributed solar, storage, heat pumps, microgrids, and digital control systems, Europe can create an architecture that is inherently less exposed to geopolitical pressure. For example, in Ukraine, decentralized solar solutions with batteries are helping to resist Russian attacks.

A more resilient architecture relies on many small, distributed assets—such as rooftop and community-scale solar, local storage, heat pumps, microgrids, and digitally coordinated control systems—rather than a few large, centralized installations. If one component fails, others keep operating; if a local battery goes offline, it does not trigger a blackout. This stands in sharp contrast to the loss of a single pipeline, LNG terminal, or transmission line. A decentralized system has no single point of failure; the disruption of one node does not cascade across the entire network. This significantly lowers the effectiveness of energy coercion, whether it comes from PetroStates manipulating fuel flows or from ElectroState suppliers attempting to hack the grid.

This design philosophy—emphasizing modularity, flexibility, and rapid recoverability—is what we have described as AdapTech, in “AdapTech: Resilience-Driven Innovation in Energy Systems.” In a US-China bipolar environment, AdapTech provides strategic insulation and lowers dependency on any individual supplier. A faulty inverter or compromised software module can be replaced without halting system operations. Hardware can be replaced incrementally; software can be updated or switched with minimal disruption. This stands in sharp contrast to large, monolithic assets that bind Europe to specific technologies, specific fuels, or specific political conditions and that can be easily targeted in the event of military conflict.

Importantly, AdapTech does not require Europe to replace its integrated power system with thousands of standalone microgrids. It is an overlay, not a replacement. In practice, implementation can begin quickly and at reasonable cost by focusing on the highest-value sites first: hospitals, data centers, military bases, water utilities, ports, airports, and key industrial facilities. These critical loads already require backup power and cybersecurity; upgrading them with local solar, storage, islanding capability, and secure digital controls can often be done within existing infrastructure budgets or resilience funding streams.

Most of the early steps toward AdapTech involve software, standards, and small-scale equipment rather than major capital projects. Requiring new inverters to support islanding modes, establishing cybersecurity requirements for EV chargers and heat pumps, deploying demand-response automation in buildings, or adding modular containerized batteries at critical nodes can be achieved far faster than building new pipelines or deploying power grids. Remaining nuclear and large thermal plants continue to play a role as part of the backbone system, but the edges of the grid become more flexible, more digital, and more resilient to disruption. Private consumers, in many cases, would also opt for these behind-the-meter solutions if regulatory barriers are removed and at least some financial incentives are provided.

For Europe, the practical implications are threefold:

1. Prioritize architectures over assets. Investing in flexibility—storage, demand response, and smart grids—reduces reliance on external balancing fuels and makes the whole system more robust, regardless of who supplies the underlying equipment. A flexible system is inherently less coercible.

2. Embed cybersecurity and control sovereignty at the core. As energy systems become digital, the risk shifts from physical disruption to manipulation of data and control signals. Ensuring that the digital spine of the energy system is governed by trusted actors is as important as securing physical assets. In a cyber-physical system, sovereignty resides in the code.

3. Enable rapid recovery and adaptation. AdapTech is not only about preventing disruption; it is about ensuring that systems can recover quickly when disruptions occur. Modular technologies, such as containerized batteries or plug-and-play microgrids, can be deployed or replaced within hours, not months. Modularity and standardization make repairs easier, substitution faster, and innovation more continuous—a form of resilience that large centralized systems cannot match.

This approach does not eliminate Europe’s exposure to geopolitical shocks, but it changes the nature of that exposure, making the system harder to coerce and quicker to rebound. In a world defined by two technological superpowers and increasingly fragile energy geopolitics, AdapTech is not a niche innovation strategy—it is a foundational requirement for Europe’s long-term security.

Conclusion: “Vulnerable in Between” or “Counterweight”?

In an increasingly bipolar energy world dominated by the United States and China, Europe faces a stark choice about its future role. It can drift into the position of a vulnerable in between, vulnerable to both the molecular powers and the electron empires. This path would leave Europe squeezed by external forces, reacting to geopolitical shifts rather than shaping them. A continent that merely absorbs shocks will find its strategic space progressively narrowed and could be more easily vanquished in the case of an armed conflict.

But Europe also holds the potential to pursue a different trajectory: becoming a counterweight. Rather than aspiring to be a third pole—an unrealistic goal given its resource base and industrial structure, even within the “Good Guys Alliance”—Europe can influence how bipolar competition plays out. Through demand reduction, strategic electrification, selective tech sovereignty, and resilient system architectures, especially if it can convince other countries to join the effort (the “Good Guys Alliance”), the EU can shift the energy order away from coercive dependence and toward more rules-based, interoperable, democratic forms of interdependence. In this role, Europe does not challenge the superpowers head-on; it reshapes the environment in which they operate.

This path aligns with Europe’s strengths: its value as a market, the power to set standards, shape global practices, and define the governance of emerging technologies. It enables the EU to build a resilient, democratic, tech-sovereign energy model, leveraging its regulatory and market influence not as blunt instruments, but as precision tools that enhance rather than undermine strategic autonomy. Europe’s value lies not in scale, but in its ability to write rules and build systems that others must navigate.

Choosing this path requires more than ambition. It demands embracing hybridity, recognizing that Europe will continue to rely on both molecules and electrons—albeit more on the latter than the former; investing in autonomy, especially in the technological and digital foundations of the electrified system; and confronting internal contradictions around cost, permitting, political will, and the uneven capacities of member states. Without resolving these internal tensions, Europe’s external strategy cannot succeed.

Europe cannot choose the world’s polarity, but it can choose its role within it: either a victim navigating pressure from two superpowers, or a system modifier shaping the operating rules of a world increasingly defined by them. The difference lies in whether Europe continues to react to external shocks—or begins to redesign the system in which those shocks occur. The next five years will determine which of these futures Europe inhabits, and whether it retains meaningful strategic agency in a rapidly changing global order.

About the Authors: Tatiana Mitrova and Anne-Sophie Corbeau

Tatiana Mitrova is a global research fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy and director of the New Energy Advancement Hub.

Anne-Sophie Corbeau is a global research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy and a visiting professor at SciencesPo.

Image: Billion Photos/shutterstock