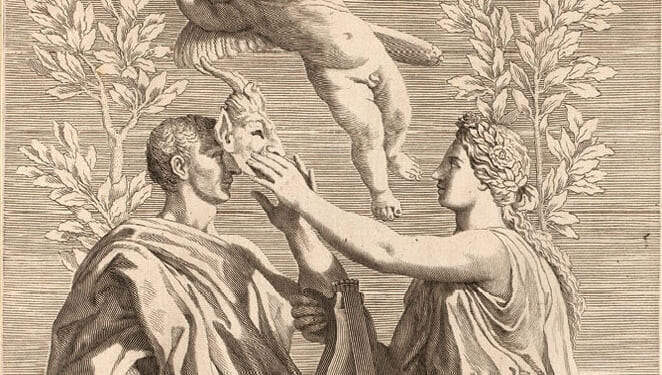

Horace: Poet on a Volcano, by Peter Stothard (Yale University Press): Peter Stothard, a classicist and the former editor of the London Times Literary Supplement, has written a pert, canny, and enchanting biography of one of my favorite poets, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, known to us as Horace. The short, chubby son of a former slave, Horace lived in tumultuous times. He was born in Venusia, the “city of Venus,” two-thirds of the way down the Appian Way toward Brundisium in 65 B.C. The Roman Republic was in a terminal state. Marius and Sulla had essentially finished it off in the preceding decades with their brutal proscriptions and civil war. Julius Caesar delivered the coup de grâce, or maybe it was only the official interment, after his return from Gaul in 49 B.C. In the aftermath of Caesar’s murder in 44 B.C., the young Horace took the side of Brutus and the assassins. Though hardly warlike, he fought with them against Octavian (the future Augustus) and Mark Antony in 42 B.C. at Philippi in Macedonia. Remarkably, he was reprieved by the victors. On the strength of some early erotic poems (Satires and Epodes), he was taken under the wing of Maecenas, Octavian’s cultural advisor and chief patron of poets, who gave him a farm some thirty miles east of Rome in the Sabine Hills. It was there that Horace worked his most memorable magic in four books of Odes. Horace’s primary metrical models were the Greek lyric poets Archilochus, Sappho, and Alcaeus. The intricate, elegant, sophisticated linguistic spell that Horace cast had never been wrought before in Latin. As Stothard notes, “Horace’s art of molding the sounds of the Greeks to the language of the Romans stretched what was possible toward what for many was beyond the possible.” The result was both intense and sublimely, seductively elusive. It was also hauntingly memorable. Even today, we know many of Horace’s coinages: in medias res (good advice as a starting point for aspiring storytellers), ut pictura poesis, sapere aude, nil desperandum, dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, and many others. What do you say when you want to boast that something you’ve made will last a long time? Why, you say you have made monumentum aere perennius, “a monument more lasting than bronze.” Then of course there is carpe diem, “seize the day,” a brief imperative that may be said to summarize Horace’s philosophy of life: “sapias, vina liques, et spatio brevi/ spem longam reseces. dum loquimur, fugerit invida/ aetas: carpe diem. quam minimum credula postero.” “Be wise, strain the wine, cut back long hope into our short space. Even while we are talking, envious time has fled away: seize the day, trust least in the future.” Note the presence of wine. It is an honored character in many of Horace’s poems. Nulla placere diu nec vivere carmina possunt/ quae scribuntur aquae potoribus. “No poems can give pleasure for long, or last, which are written by drinkers of water.” —RK

In God’s Image: How Western Civilization Was Shaped by a Revolutionary Idea, by Tomer Persico (NYU Press): “It is a basic human right (humanum ius) that everyone should be free to worship according to his own convictions.” This pronouncement comes not from any UN charter, but from the early Christian theologian Tertullian (ca. 155–220). Through the lens of Genesis 1, Tomer Persico explores in his recent book In God’s Image how the idea of religious freedom developed and in turn became the catalyst for the rise of the individualist modern self. Much of the book is an incisive recapitulation of well-trodden scholarly ground, with chapters dedicated to Paul’s insistence on a personal, internal relationship with God—an idea that, when taken up again by the Protestant reformers in the sixteenth century, ultimately led to the liberty of conscience we now take for granted in the West. In God’s Image is at its most insightful when dealing with the “Jewish question” in medieval and early modern Europe, showing how the Western notions of natural law, human rights, and national citizenship all helped to transform a distinct “nation within a nation” into a mere religio that could be assimilated into the broader European culture. —AG

“To the Holy Sepulcher: Treasures from the Terra Sancta Museum,” at The Frick Collection (opening October 2, 2025): Since its rediscovery in the fourth century, the location of Jesus’s tomb—the Holy Sepulcher—has been the most important pilgrimage site in Christendom. Now the treasures from its Terra Sancta Museum, donated to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher by European monarchs and emperors in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, will make their first pilgrimage stateside through an unprecedented loan exhibition at The Frick Collection. Demonstrating the finest goldsmithing and textile work of the time—with similar examples no longer extant in Europe—“To the Holy Sepulcher: Treasures from the Terra Sancta Museum” will present a landmark display of European decorative arts in what will be the final Frick exhibition organized by Xavier F. Salomon, the museum’s Deputy Director and Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator, before his departure for the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon, Portugal. —JP

“Elevating Stewardship: Restoring and Reviving Iconic House Museums,” with Jennifer Carlquist, Robert Leath, and Patricia Lowe Smith, moderated by Benjamin Prosky, at the General Society Library (September 24): House museums offer a unique opportunity for visitors to step back in time. But in their appeal lies their difficulty: an old home can present maintenance challenges that far exceed those of purpose-built museum spaces. On September 24, three museum professionals overseeing restoration work at house museums across the country will discuss the processes at their respective locations. Of local interest: Robert Leath will detail the reinstallation of woodwork at the Cupola House (1756–58) in Edenton, North Carolina; that paneling had been in the Brooklyn Museum since 1918. The talk is presented by the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art and sponsored by the Richard Hampton Jenrette Foundation. —BR

The Empire State Rare Book and Print Fair, at Vanderbilt Hall, Grand Central Terminal (September 26–28): Fall brings the Empire State Rare Book and Print Fair to town, a more digestible alternative to the sprawling aisles of the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair in the spring. The fair will take place this Friday, Saturday, and Sunday in Grand Central Terminal’s Vanderbilt Hall, offering attendees a chance to browse first editions, manuscripts, letters, prints, maps, ephemera, and more from thirty-five vendors. For the bibliophile or the lover of history in general, chances such as this to interact with precious objects firsthand should not be missed. —IS

Dispatch:

“Unraveling Ravel,” by Max Sligh. On Maurice Ravel, by Emily Kilpatrick.

By the Editors:

“Inside the cult of Equinox”

James Panero, The Spectator World

From the Archives:

“Love letter to a language,” by Wiliam Jay Smith (September 1991). On An Essay on French Verse: For Readers of English Poetry, by Jacques Barzun.