Note: If joining “Saintly Influencers” for the first time today, please read the footnote, explaining its context, purpose, and aim.

The twentieth century was an incredibly important age, for both the world and the Church. During that period, the world witnessed the culmination of ideas and cultural patterns that had been set in motion from the end of the Middle Ages. In the same century, the Church fostered the lives of several saints whose words and work influenced—even transformed—the world. The influence of these holy men and women continues into the third Christian millennium.

Pope St. Pius X

The first saintly influencer of the twentieth century was Pope Pius X (1835-1914). His service to the universal Church was guided by his motto, Instaurare omnia in Christo (in English, “To Restore All Things in Christ”). His program meant to provide solid teaching and “contribute largely to temporal welfare and the advantage of human society,” which would bring about justice in society and tranquility in culture (E Supremi, 4, 14). He conveyed his vision for a more just, peaceful, and joyful future through a litany of encyclicals and exhortations on important doctrinal and social topics, which charted the Church’s navigation of what would be a very turbulent century.

It is specifically by one instruction, though, that St. Pius X influenced Catholic culture in the twentieth century and beyond: his decision to lower the requisite age for receiving First Holy Communion to the age of reason.

It happened that children in their innocence were forced away from the embrace of Christ and deprived of the food of their interior life; and from this it also happened that in their youth, destitute of this strong help, surrounded by so many temptations, they lost their innocence and fell into vicious habits even before tasting of the Sacred Mysteries. (Quam Singulari)

Quite simply, followers of Jesus needed access to the graces of the Eucharist at earlier ages so they would not fall prey so easily to the wiles of the devil.

St. Katharine Drexel

The next influencer, like St. Pius X, was born in the middle of the nineteenth century, but exercised greatest influence after 1900. Katharine Drexel (1858-1955) was born into a wealthy Philadelphia family, and she enjoyed the finest things high society had to offer. At the same time, her parents exemplified piety and works of mercy, to which she was deeply attracted.

As a young girl, she read Helen Hunt Jackson’s A Century of Dishonor, which opened her eyes to the plight of Native American tribes. She made a personal request to Pope Leo XIII to send missionaries to the American West, but instead of sending missionaries, the pope encouraged her to become a missionary.

Near the end of the nineteenth century, she began her mission to tribes in North Dakota and New Mexico and, soon after, founded the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. When professing her vows as the superior of that new religious community, she promised “to be the Mother and Servant of the Indian and Negro Races” and never to undertake any work that might lead to the “neglect and abandonment” of these groups.

Relying on the Church’s constant teaching on human dignity and development, Mother Katharine facilitated the opening of many schools to serve these marginalized populations, including Xavier University in Louisiana in 1925. All told, her missionary disposition and actions laid at least part of the foundation for the American Civil Rights Movement that burgeoned in the 1950s and 1960s.

Pope St. John XXIII

Pope John XXIII (born Angelo Roncalli, 1881-1963) bears a significant influence on Catholic culture in the western world, specifically because of the “flash of heavenly light” that led to the convocation of the Second Vatican Council. Although he only presided over the first session, the council was held at a watershed moment in world history; and it was unique in the history of the Church because it had not been called in response to a singular theological or pastoral issue needing to be addressed.

The Council initiated a transition—a revolution, even—in how people understood the Church; how Catholics understood themselves; and how Catholics of every vocation and state of life are called to bear the light of Jesus in the world. One of the greatest fruits of the Council was to convince “ordinary” Catholics that they, too, had (have) an important role to play in the work of the Body of Christ; and we are living in an historical moment when so many have begun to realize that truth. This fostered another great fruit of the Council: that the Church would engage with the world rather than withdraw from it.

St. Josemaria Escrivá

Josemaria Escrivá (1902-1975) was a Spanish priest who advance the message that the laity can be holy, too. He founded Opus Dei, a religious association that aimed to help lay persons harness the grace God makes available, and to share joyfully that grace in the world.

In a homily titled “In Joseph’s Workshop” (from March 1963), Escrivá preached that holiness was to be found in “ordinary work, professional work carried out in the midst of the world.” That work, he continued, gave Christians a mission “to bear witness to Christ before our fellow men and so draw all things toward God” (45). Said differently, Escrivá was exhorting “average,” faithful Christians to answer the universal call to holiness, which would be specifically defined by the Second Vatican Council just over a year later.

St. Mother Teresa of Calcutta

Another influencer, Anjezë Bojaxhiu (1910-1997), was a young Albanian woman who joined the Sisters of Loretto after she discerned a call to teaching. She was sent to Calcutta, India, for her mission—a city which contained some of the world’s poorest slums. There, she became aware of the grave poverty and felt a call to relieve it in what small ways she could. Thus, she formed a new religious community, the Missionaries of Charity. Within just a few years, the community was expanding to large cities across India and the world to minister in the same way.

In 1969, a British journalist and filmmaker, Malcolm Muggeridge, produced a documentary on the community’s work for the BBC, entitled Something Beautiful for God. In his interviews with Mother Teresa, she told him of the core of the community’s mission: “being unwanted…is the worst disease that any human being can ever experience.” Thus, the mission of Mother Teresa and her sisters was to “make them feel that they are wanted, we want them to know that there are people who really love them, who really want them…to know human and divine love.”

Service to the poorest of the poor revealed the saintly woman’s devotion to Jesus and caused many women to join her apostolate. But it was Muggeridge’s documentary that catapulted her into a position of cultural influence that allowed her community’s mission work to spread; landed her many audiences with popes; brought her to speak before the United Nations; and earned her a Nobel Peace Prize in 1979.

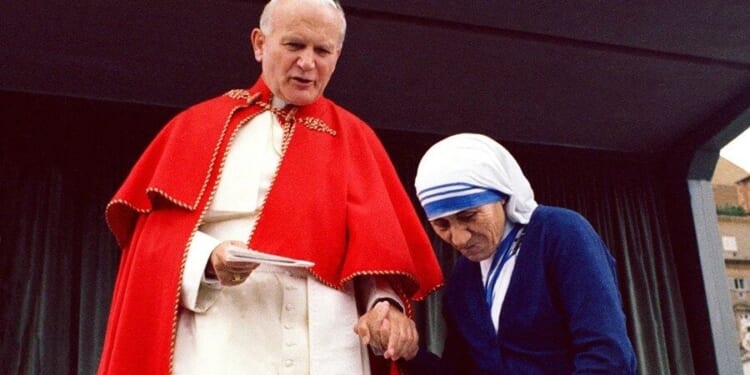

Pope St. John Paul II

The last saint may have borne the greatest influence of all, especially as the twentieth century turned to the twenty-first. Pope John Paul II (1920-2005) was elected in October 1979. It is not an overstatement to say that he ignited a cultural revolution felt throughout the Church and the secular world. That revolution was based in the Church’s proclamation about human dignity and freedom. In his very first encyclical letter, Redemptor Hominis, which laid out the vision for his pontificate, he wrote:

Since man’s true freedom is not found in everything that the various systems and individuals see and propagate as freedom, the Church, because of her divine mission, becomes all the more the guardian of this freedom, which is the condition and basis for the human person’s true dignity. (12)

From that foundational idea, for twenty-six years and into the new millennium, he reminded global culture of the dignity of human life; he initiated the World Youth Day movement; he cultivated a generation of dynamically orthodox priests; and he played a pivotal role in the downfall of communism in eastern Europe the late-1980s.

Conclusion

St. John Paul the Great’s gift to the Church and the world for the new millennium makes a fitting image to conclude this look at the cultural influencers of the twentieth century. Certainly, he was a great witness to hope, but he was that because he believed deeply in God’s great mercy. Through ten decades, the saintly pontiff and the other influencers of the century had witnessed the worst that humanity could do. Because of that, John Paul made sure the faithful had access to the avenues of grace that would be most beneficial into the future. So, the first saint he canonized in the new millennium was Faustina Kowalska, the Apostle of the Divine Mercy. A significant part of his legacy and influence is clearly reminding the Church and the world of our greatest need—Divine Mercy—in progressing through the remainder of history’s unforeseen vicissitudes.

Editor’s Note: Thank you for joining us on this journey through Christian history in our Saintly Influencers series. Let us continually ask the patronage of these spiritual heroes as we seek to become saints in our own time.

[1] Learning about the lives of holy men and women is a common and helpful spiritual practice. But while we might take some time to consider saints in their historical contexts, it’s easy to look past the ways their lives and actions influence our own present culture. Saints are made within specific cultural, historical circumstances and, just as importantly, they have borne deep impact on this current age of history.

Thus, this series seeks to identify the saints from the history of our Church who have borne the greatest influence on our present culture, that is, the way we think about and experience the Christian life in our current era, and in our segment of geography (i.e., the West and, in particular, the United States). This series delineates Christian history into eight ages: the Apostolic Age (A.D. 35-100); the Early Patristic Age (A.D. 100-480); the Later Patristic Age (A.D. 480-800); the Age of Early Christendom (A.D. 800-1200); the Age of Later Christendom (A.D. 1200-1400); the Renaissance and Baroque Age (A.D. 1400-1660); the Modern Age (A.D. 1660-1900); and the Post-Modern Age (the twentieth century). Each essay within this series will examine a handful of saints who sought and found holiness within their historical epochs and who, in turn, have borne an outsized influence on the ways Catholic-Christians in the third millennium understand and live the Catholic Faith. These few in each essay are chosen from among many, many other saints whose influence could be included in this series as well.

The great hope is that learning these influences gives us inspiration and stamina as we seek to answer the call to holiness in the world and the culture of the twenty-first century.

Photo of Mother Teresa and John Paul II, May 25, 1983, from L’Osservatore Romano / Vatican Media