“All Americans born between 1890 and 1945 wanted to be movie stars,” wrote Gore Vidal. Robert Redford was an exception. He was an aspiring painter who made a truce with his professional destiny. His handsomeness enchanted moviegoers and magazine editors, but he was more motivated by the acting craft than vanity. He avoided Hollywood during its last golden age and found refuge outside Provo, Utah, on his majestic ranch—initially a two-acre purchase in 1961 when he had some dollars to spare with an uncertain acting future. He died there in his sleep on Tuesday at 89.

All Americans born before digital living remember Redford’s cinematic magnetism on the big screen. He was the last all-American movie star.

Redford’s persona—masculine and charming, the dashing, enigmatic outlaw—was nurtured in Santa Monica. He was born there in 1936, the son of a Scots-Irish milkman-turned-accountant father and mother who died when he was 18. In time, the family moved to the San Fernando Valley, “a great sea of nothing,” as Redford described it in a 1998 New Yorker profile, where he spent his time playing “sports and getting into trouble. And cruising and getting into trouble.” He went to the same high school as Natalie Wood, a contemporary and future co-star.

Following a short stint at the University of Colorado, Redford went to Paris. He dreamt of post-Impressionists, not big screens. But Paris was a bust. He landed in New York, went to Pratt, married a young Mormon from Provo, and started acting with walk-ons and television appearances. “I felt I could do it. I hadn’t had much experience, but when I got into it, when I shifted from art to acting, something happened very naturally, and then I took it seriously and worked hard at it, and then I developed a curious confidence about it,” he told The New Yorker. “I knew I could do it better than a lot of people. And I don’t know why.”

It was during this time, the Kennedy years, that Redford starred in a haunting 1962 episode of The Twilight Zone. In “Nothing in the Dark,” a young Redford plays Mr. Death seeking a reclusive old woman, who fears her expiration date. Fearing his arrival, she won’t accept visitors, and spends her cold, lonely days in a basement tenement. Mr. Death finds his clever way in. “The running is over,” Redford’s character tells her. “What you feared would come like an explosion is like a whisper,” he reassures. “What you thought was the end was the beginning.”

It was also the beginning of Redford’s acting ascent. “I’m interested in that thing that happens where there’s a breaking point for some people and not for others,” Redford told Maureen Dowd in a 2013 New York Times profile. “You go through such hardship, things that are almost impossibly difficult, and there’s no sign that it’s going to get any better, and that’s the point when people quit. But some don’t.” In his early twenties, Redford almost quit following a stage flop in New York and the death of his baby son, whose funeral he could barely afford. An intensely private man, he wanted out of the scene. “There was always this thing about Redford that he didn’t really want to be an actor. He wanted to be a painter,” recalled actress Elizabeth Ashley in Mark Harris’s biography of director Mike Nichols. “Bob was a little finer—he was an artist, and we were showbiz trash.”

Nichols spotted Redford’s fine actor qualities in his role as a struggling writer in an episode of Alcoa Playhouse. “I experienced that frisson you get when you’re surprised by someone,” he said. “It wasn’t ‘Gee, he was interesting.’ It was more ‘Where the hell did he come from?’ I just thought, he’s gonna crack it.” Nichols wanted to direct Redford in a new play by Neil Simon. Barefoot in the Park, initially running as Nobody Loves Me in suburban Philadelphia’s Bucks County, made its Broadway debut just days before Kennedy’s assassination.

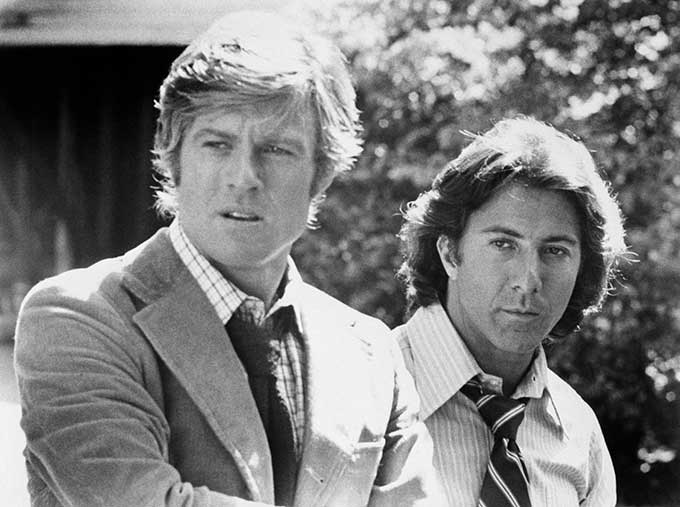

Through the 1960s, Redford and Nichols followed a fortuitous path in celluloid, though Redford turned down the role of Nick in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Nichols, in turn, rejected Redford for the lead of Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate. “You can’t play a loser,” Nichols told him. “Look at you. How many times have you struck out with a woman?” A dumbfounded Redford responded, “What do you mean?” Nichols concluded, “That’s how I learned Benjamin can’t be a winner.” Dustin Hoffman got the part.

Neither Redford’s good looks nor acting talent assured his future as a leading man, especially in an era dominated by the likes of Steve McQueen and Paul Newman. But he eventually became the era’s defining movie star. He possessed an enduring American sensibility—a blend of cool and regal, charm and rebellion. He broke the generation gap and drew young and old, men and women, to catch a glimpse of him. His looks weathered with age and time. “I never had a problem with my face on screen,” he told Dowd. “I thought it is what it is, and I was turned off by actors and actresses that tried to keep themselves young.”

To watch Redford is a rendezvous with the best of twentieth-century American film. His breakout, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, was a story of friendship—co-starring Newman—between two outlaws. It was the top-grossing film of 1969 and nominated for seven Oscars. It was his gateway to stardom in the 1970s. In 1973, Redford co-starred with Newman again in The Sting, set in the year of Redford’s birth, another tale of outlaw friendship. He positioned himself as a romantic leading man in The Way We Were with Barbara Streisand; attempted The Great Gatsby (“You can’t get that on screen, and filmmakers have never understood that,” said Vidal); traversed the wilderness as a mountain man in Jeremiah Johnson; exhibited his Kennedy-esque looks in The Candidate; revisited a political cataclysm in All the President’s Men; and chilled with his CIA role in Three Days of the Condor, among the only films shot inside the Twin Towers. In 1984, he starred in The Natural, a mythic film about the fictional baseball player Roy Hobbs.

Over time, Redford acted less, directed more, and channeled his energy into the Sundance Institute, which launched a new age of independent movies with its film festival and nurtured talent like Steven Soderbergh and Quentin Tarantino, whose 2019 Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is an homage to those Redford–Newman films of friendship. An environmentalist, Redford believed in conserving natural beauty, an impulse that set the stage for his 1992 directed film, A River Runs Through it, based on Norman Maclean’s 1976 novel of brotherhood and fly fishing in early twentieth-century Montana. In the film, narrated by Redford, the stoic father asks his son, Norman, about his dead brother, Paul. “Maybe all I know about Paul is that he was a fine fisherman,” says Norman, voiced by Redford. “You know more than that,” the father replies. “He was beautiful.” Millions felt that way about Robert Redford.

Top Photo by George Pimentel/WireImage