“Building Models: The Shape of Painting” is about a kind of painting that has for decades been called “shaped canvas,” although many examples of it aren’t canvases at all, and some are more like sculpture. Enthusiasm for this type of painting burgeoned in the 1960s, a period replete with innovation in artistic forms. As is apparent in the work of Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and Lee Bontecou, the shaped canvas evolved from abstract painting, which, while emphasizing flatness, in those years was foregrounding its own physical and material nature. One of the breakthroughs in the rise of the shaped canvas came with the inclusion of figurative elements, as seen in works by Robert Rauschenberg and Red Grooms.

Three-dimensional painting goes back to the beginning of art. Humans thirty thousand years ago painted on the bulges of cave walls with the effect of enhancing the realism and vitality of painted animals. In more recent centuries, the common three-dimensional mixing of painting and sculpture in reliefs has resulted in some extraordinary achievements, such as Luca and Andrea della Robbia’s terracotta reliefs. From the late-medieval period onwards, paintings and sculptures in churches have commonly formed part of altarpieces, those assemblages of paintings of different shapes and sizes meant to be read as one object.

It is therefore appropriate that this exhibition, curated by Saul Ostrow, is located in the former Resnick-Passlof studio on Eldridge Street, which was a synagogue in its first incarnation. The shape of the gallery, long, high, and relatively narrow, has the aura of a religious space, with the current artwork mostly on the sidewalls, as in a chapel.

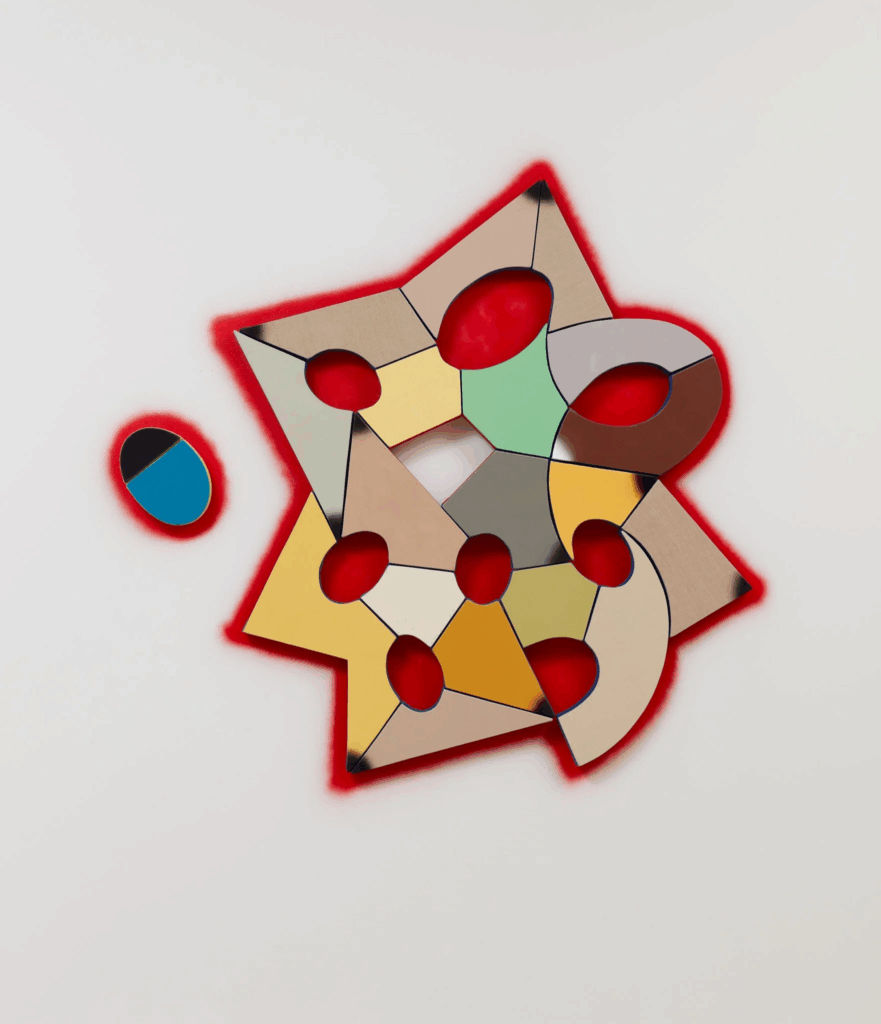

Upon entering the main gallery, you are presented with, at the far end, Pinwheel (2024–25), a lively, complex, and colorful work by Gwenael Kerlidou. The emphasis is well deserved. One of its unique qualities is that it is partly spray-painted right on the wall as well as hung on it. And like Luca della Robbia’s larger sculptures Kerlidou’s work is made up of many separate pieces, but with one part of the work detached from the rest. Thus it literally includes the room in which it is situated, unlike the other works in the show that only engage with the space insofar as they are three-dimensional and irregular in shape. This piece points to a lively future for this form of art, at least in Kerlidou’s hands.

On the left-hand wall, the viewer’s gaze is captured by a looming presence. Spice of Life II (2017) is a relatively recent example of a form used repeatedly by Ron Gorchov since he invented it in the early 1970s. Employing only two colors (a black background with two thick convex red strokes in the middle) painted on a largescale, bending canvas that appears both concave and convex, Spice of Life II is a good representation of Gorchov’s interest in playing with perception. Every time you see one of his works, it is an “aha!” moment. At the same time, one wonders whether this replication is getting old. Still, it is undeniable that Gorchov created one of the motifs most associated with the shaped-canvas movement.

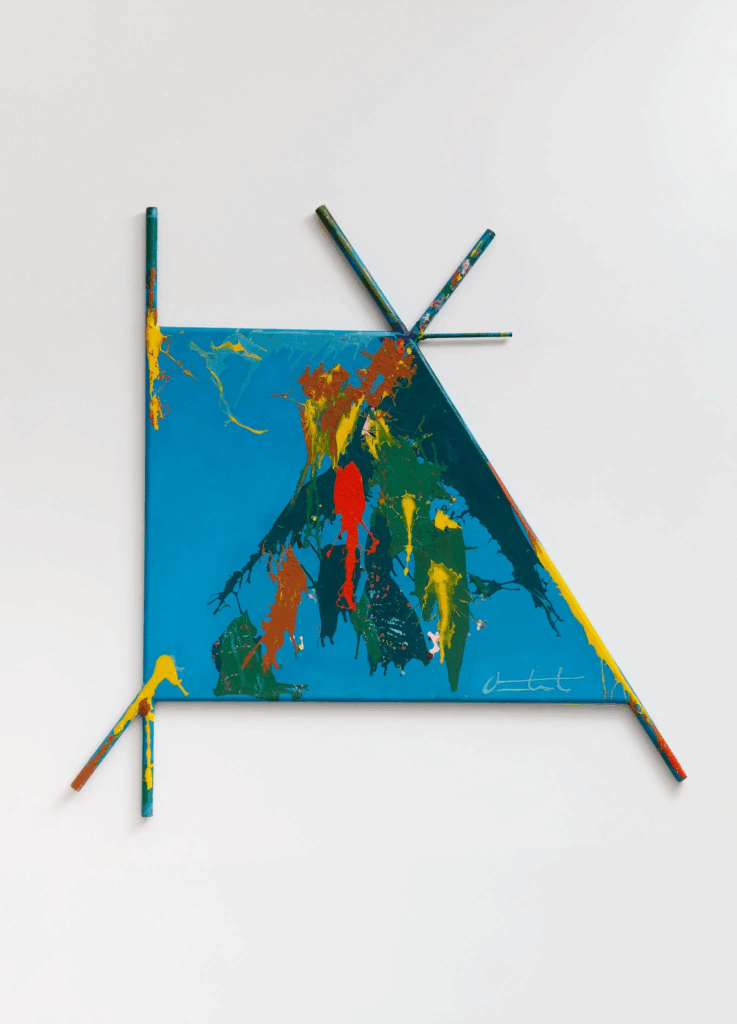

Upstairs in the second gallery, an untitled piece by Joe Overstreet (1982) combines painting and sculpture in a flat, linear structure made of pipes with an irregularly shaped painted canvas wrapped around it. The ends of the pipes stick out prominently. The painting part is colorful and expressionistic, and together the canvas and pipes, seemingly in conflict with one another, are reminiscent of a flattened tepee, waiting to be pulled up into the full three dimensions.

All ten artists in the show—Ron Gorchov, Gwenael Kerlidou, Russell Maltz, Joe Overstreet, Joanna Pousette-Dart, Harvey Quaytman, Ruth Root, David Row, Ted Stamm, Li Trincere—have well-deserved reputations, but not all are equally well served by their work’s selection for the show. Conversely, there were some artists conspicuous by their absence, such as Elizabeth Murray. Her colorful, inventive, and uniquely driven spirit would have been welcome.

Early in my own life as a painter, I worked exclusively with shaped and three-dimensional painting from about 1965 to 1975, when that new kind of art had its heyday. The shaped work still offered opportunity for innovation, whereas there seemed to be far less room for making something new and comprehensive with a traditional canvas. Eventually I came to see a normal canvas as more challenging, partly because of its long and extraordinarily rich history. Painting on a regular canvas also required a lot less carpentry. After all, as Doug Ohlson pointed out, a flat, rectangular canvas is also a shaped canvas, and its use over many centuries indicates a singular capacity for creating new meaning.