When did the devil disappear? The image of Satan persists, but mostly as kitsch. The few who believe in him are typically portrayed as unserious, even gauche. The prevailing view holds that progress has vanquished the superstitions of earlier, more fearful, eras. It matters little, apparently, that the twentieth century was the bloodiest in history.

One could accuse the Reformation of diluting Christianity or suggest that the Enlightenment banished the Prince of Darkness. One might blame Copernicus or Nietzsche. Carl Jung speculated on the devil being “the grotesque and sinister side of the unconscious.” Why invoke the devil when man had exceeded him in cruelty? Even Pope Francis reportedly claimed that hell doesn’t exist. Humanity’s ruin is our own.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

For Voltaire, the Great Lisbon Earthquake was inconsistent with a just and omnipotent God. That the resulting firestorm was fueled by candles lit for All Saints’ Day added to the celestial nihilism. “The eighteenth century used the word Lisbon,” philosopher Susan Nieman claims, “much as we use the word Auschwitz today.” In other words, God was among the bodies; the devil was superfluous.

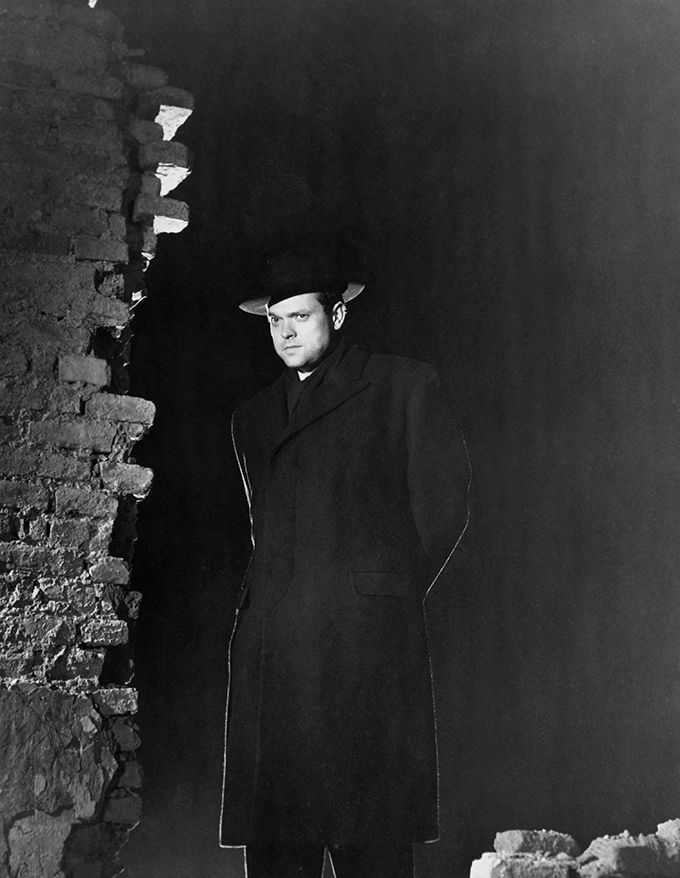

But does disappearance equal destruction? “My dear brethren, do not ever forget,” Baudelaire wrote, “that the loveliest trick of the Devil is to persuade you that he doesn’t exist!” A version of the phrase returns in the 1995 neo-noir film The Usual Suspects. The villain Keyser Söze is the zenith of evil, so ruthless that he kills his own family to spite their kidnappers. Söze is a bogeyman for adults, the embodiment of conspiracy with tendrils everywhere. Strip away the horns and pitchfork, and what remains is the thing itself: evil. Whether personified or abstract, it refuses to disappear.

To be agnostic to evil, as some are today, is to exist in rarefied privilege. If you don’t believe in evil, you haven’t lived enough. However medieval, hysterical, or unsophisticated it may seem, stand in Dachau or Cambodia’s S-21 and you will feel it still. “Were a stranger to drop, on a sudden, into this world,” the arch-skeptic David Hume noted, “I would show him, as a specimen of its ills, an hospital full of disease, a prison crowded with malefactors and debtors, a field of battle strowed with carcasses, a fleet foundering in the ocean, a nation languishing under tyranny, famine, or pestilence.”

To define or quantify evil is to try to contain and control it. Yet evil is insidious and shape-shifting. If you think you’re exempt, you’re vulnerable. The lessons of Reserve Police Battalion 101, the Stanford Prison Experiment, and the Milgram experiments—in each, ordinary people, placed under particular social pressures, engaged in actions they might otherwise find reprehensible—suggest that the odds of defying authority and resisting evil are slim.

One of the most significant cultural confrontations with evil occurred during the trial of Adolf Eichmann, where Hannah Arendt observed one of the architects of the Holocaust. Her account challenged the preexisting orthodoxy of evil as a debased form of heroism. Eichmann, she noted, “was not Iago and not Macbeth. . . . Except for an extraordinary diligence in looking out for his personal advancement, he had no motives at all.” This was not the deranged baby-bayoneting Boche of the World War I yellow press or the mythic Teutonic Übermensch, in her view, but a diligent functionary. “The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal.” Arendt’s phrase “the banality of evil” became so pervasive that it formed a new, unintended orthodoxy. Evil was now dissociative, bureaucratic, institutional. This understanding provided a distance—plausible deniability—that the Nuremberg trials rejected but that nevertheless entered the discourse. Evil, in this view, was structural rather than the result of human decisions—a result of obedience and passivity, not active malice.

It scarcely matters, though, whether genocide is committed with hot or cold blood, warped passion or distorted logic. World War II saw plenty of gothic-level evil, from the Dirlewanger Brigade to the gates of Jasenovac. The Doctors’ Trial revealed how easily the line between rationalized detachment and sadistic cruelty could blur. Arendt was right to highlight the bureaucratization of evil afforded by modernity, but her insight should have been added to, instead of replacing, the existing understanding of evil’s many forms, which history has long demonstrated.

The further we moved from war, though—the most brutal reality check—the more evil disguised itself, and even, like the devil, seemed to vanish. The media have played a central role in this process, through embedded reporting and sanitized coverage, as has the rise of remote-control warfare. All of it abstracts away from suffering. During the mediatized Gulf War, the French thinker Jean Baudrillard spoke of “war stripped of its passions, its phantasms, its finery, its veils, its violence, its images; war stripped bare by its technicians even, and then reclothed by them with all the artifices of electronics.” It is immeasurably more so now. Much of modern warfare involves detaching the perpetrator from the consequences of his actions.

Noir exists in opposition to this. Created in a postwar environment, it remains one of the few places where true evil still gets treated as if it exists. Noir could see that sentimentality was the real cynicism. The last words of SS officer Theodora Binz, the scourge of Ravensbrück, were: “I hope you will not think we are all evil people.” Noir locates the diabolical manifest among and within us, from the individual corruption of The Third Man to the societal degradation of Chinatown.

Many noir/hard-boiled writers had firsthand experience of war or military life. Mickey Spillane was a fighter pilot and William P. McGivern a sergeant. William Lindsay Gresham was a medic in the Spanish Civil War. Auguste Le Breton served in the French Resistance. Gerald Butler wrote Kiss the Blood Off My Hands in bomb shelters during the Blitz. Assigned to observation posts, James M. Cain was lucky to survive being gassed. Dashiel Hammett endured not one but two world wars.

Social psychologist Ronnie Janoff-Bulman’s “shattered assumptions” theory has relevance in this context. Few returnees from the wars could return to prelapsarian innocence; as they came home, many were disgusted by what they saw as a callow society. Some, like the lead character in Dorothy B. Hughes’s In a Lonely Place, brought the violence back to unleash upon innocents. Few could forget what they’d survived and seen. In David Goodis’s Down There (filmed as Shoot the Piano Player), for instance, it’s haunting how thin the ice of civilization really is.

Crucial to noir was its fidelity to life. “I make no conscious effort to be tough, or hard-boiled, or grim,” Cain noted. “I never forget that the average man, from the fields, the streets, the bars, the offices, and even the gutters of his country, has acquired a vividness of speech that goes beyond anything I could invent, and that if I stick to this heritage, this logos of the American countryside, I shall attain a maximum of effectiveness with very little effort.”

That this was still a radical proposition decades later, when Elmore Leonard dared to write how people actually speak, says much about literature and who is allowed to write it. As Raymond Chandler said of Hammett, he took “murder out of the Venetian vase and dropped it into the alley. . . . He wrote at first (and almost to the end) for people with a sharp, aggressive attitude to life. They were not afraid of the seamy side of things; they lived there. Violence did not dismay them; it was right down their street.”

Charles Bukowski suggested that writers stop writing for a decade and get a job to give them experience, a repository of stories, and a developed worldview. For contemporary literature—filled with the fads of academia and the shallows of autofiction—this was a road largely untaken. Noir writers, by contrast, rarely lost connection with the raw edge of existence.

Some noir writers were street reporters—journalists like Cain, Elliott Chaze, and Jonathan Latimer—who encountered the best and worst of humanity. Marginalization was often a hidden strength for them. As Edna O’Brien told her student Walter Mosley, “You’re black, Jewish, with a poor upbringing; there are riches therein.” Many noir writers—Chandler and Gresham among them—were heavy drinkers, frequenting seedy bars where desperation and deceit were easy to find. (Goodis did so without even drinking.) Horace McCoy worked as a bouncer. W. R. Burnett was a night clerk in a run-down hotel. Affairs were common, providing an education in the mechanics of desire and betrayal. Crime was no abstraction: Hammett was a Pinkerton detective, while Jim Thompson’s father was a sheriff accused of corruption. Thompson himself worked in hotels and oil fields, surrounded by itinerants with colorful, often criminal, pasts. These writers were observers, travelers through the social margins—an approach increasingly replaced today by insular introspection, the paralysis of political correctness, and a disconnection from real life.

Noir didn’t ignore interiority, but its practitioners were never constrained by it. To understand the self, they believed, one needed to understand the world around it. Cain’s Serenade was inspired by his travels in Guatemala; The Moth drew from his encounters with boxcar-riding hobos. Noir writers didn’t have to travel far for material, provided they retained a view of the outside. Cornell Woolrich, incapacitated with a gangrenous injury, would years later turn the view from his apartment window into the basis for “It Had to Be Murder,” later made into one of Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest films, Rear Window. More “problematic” now than when it was written, Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice is a psychosexual exploration of sadomasochism, treachery, and complicity. Critics have described it as the product of a misanthropic mind—except that it was based on the real-life Ruth Snyder–Judd Gray case (as was Cain’s novel Double Indemnity). Noir’s commitment to following the money and the bodies—those reliable markers of objective reality—feels even more radical now, with today’s intelligentsia often lost in relativist absurdities.

Several noir figures, including Goodis and Vera Caspary, worked in advertising, an industry built on decoding public desires and fears. No surprise, then, that noir is fundamentally psychological: it probes the motivations behind politics, ambition, betrayal, and violence. Chandler lamented “that kind of social and emotional hypocrisy around today” in The Simple Art of Murder. “Add to it a liberal dose of intellectual pretentiousness,” he continued, “and you get the tone of the book page in your daily paper . . . carefully escorted by the trained seals of the critical fraternity, and lovingly tended and watered by certain much too powerful pressure groups. . . . Just get a little behind in your payments and you will find out how idealistic they are.”

Like all “genre” writing, noir has been treated with condescension by the literary establishment, though many heavyweights were enthralled by it, including W. H. Auden, Kingsley Amis, and T. S. Eliot. Others, like Albert Camus, revealed an affinity for the hard-boiled style. Camus, a dirt-poor pied-noir with firsthand experience of Algeria’s brutal complexities, was cast out by the Left Bank intellectual elite for his authenticity and moral clarity, especially his argument, in The Rebel, that the end is corrupted by the means. Theodor Adorno’s claim that “there can be no poetry after Auschwitz” proved false—poetry was, in fact, written in Auschwitz. But after the war, few could feign innocence or embrace naïveté. Since then, a noir shadow has prevailed over the literary climate.

Graham Greene was well acquainted with it. Rejecting a cozy job as subeditor for the Times of London, he based his writing on his own experiences in Saigon, the Congo, and Havana. A member of MI6, he was party to political intrigues and personal betrayals. A troubled Catholic, he saw that ideology warped everything but was also a cloak for base impulses. There were only antiheroes, all good was offered up for martyrdom, and evil was terrifyingly real (see Pinkie in Brighton Rock). Noir, Greene revealed, was a spiritual form. Humanity was mired in a civil war. Revenge abounded, death tolls mounted. Class was central, but so was self-damnation. Greene never exempted himself.

As a tortured young man, Greene played Russian roulette and claimed, “I had to find a religion to measure my evil against.” There’s always a sense of being watched in his work: “somewhere there was justice, and justice condemned him.” Greene exemplified the writer who never settles, is never certain, and never ceases questioning. So influential was his long, dark career of the soul that the Church summoned him to Westminster Cathedral to condemn one of his novels. Though he dismissed The Third Man as a literary work, few characters are more prophetic than Harry Lime—not an aberration running through the sewers of Vienna but a harbinger of modern moral expediency.

While the writers in this firmament covered different territory, the similarities are significant. Iris Murdoch served in a refugee camp at the end of World War II and had already seen enough to make her postlapsarian. Her work is saturated in evil and human credulity, full of charlatans and cults, whether magic or Marxism. Betrayal is perhaps her grand theme, including self-betrayal. Humans are, for all their self-attention, incapable of seeing themselves, leaving them vulnerable to receiving and inflicting evil. As charismatic as her characters may be, Murdoch’s disgust with optimism is always apparent.

For those schooled in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Muriel Spark’s work is surprisingly bleak. She worked in military intelligence during the war. Her writing is full of tormenting furies, unreliable narrators, and chaos-sowers, sometimes benevolently disguised. The Driver’s Seat is a master class in the defining traits of the devilish. Various components of evil—the abstraction of suffering, dehumanization, toying with lives for pleasure or profit—are all evident.

Perhaps the most misanthropic figure in the noir canon is Patricia Highsmith. She famously preferred snails to people, kept detailed notebooks of her hatreds, and took pleasure in seducing posh married women and breaking up relationships. Her vocation was skewed: “the unequivocal triumph of evil over good and rejoicing in it. I shall make my readers rejoice in it too. Thus, the subconscious always precedes the consciousness, or reality, as in dreams.” She recognized evil because she accepted that she, like all adults, was susceptible to it—though she indulged that susceptibility more than most. While working at Bloomingdale’s, she stalked a customer and fantasized about murdering her, an experience that later inspired The Cry of the Owl. Few writers have been so unflinchingly honest about the mirror. At the core of her most famous creation, the sociopathic narcissist Ripley, was a hollow void. She saw cynicism beneath civility’s veneer. Reading Highsmith is to purge yourself of illusion.

Where did noir go? Why are these writers out of style, and where are their heirs? Part of the answer lies in the widespread misinterpretation of Arendt’s concept of “the banality of evil.” Understanding this requires examining the current cultural climate, dominated by a class of establishment illiberal liberals. For them, suffering is abstract and distant; insulation is everything. The prevailing argument is that they’re social constructivists—everything is nurture, even crime and evil, and everything has an explanation. To explain is to absolve, even when it’s not their place to do so. If we can fix the underlying conditions for crime, they argue, crime itself will evaporate. The logical conclusion to this process could be found in the Soviet Union, where the regime covered up the crimes of figures like the Butcher of Rostov because serial killers couldn’t exist in a classless utopia. The Nazis confronted a similar paradox with the S-Bahn Murderer: he couldn’t exist within their framework of Aryan order, so he didn’t—except to his victims.

Western liberal democracies have their equivalents. In Britain, at least 1,400 young white working-class girls have been raped, tortured, and, in some cases, murdered by mostly Pakistani grooming gangs from the late 1980s until well into the 2010s. At successive points, the media, police, and other public officials have obscured the truth, engaging in a kind of societal DARVO: Deny, Attack, and Reverse Victim and Offender. Whistleblowers were silenced, punished, or branded as racists or far-right agitators, even when the victims came from traditional Labour strongholds in the formerly industrial North. Those involved in the cover-ups, and the cultural echo chamber supporting them, remain convinced of their own nobility and benevolence in trying to maintain the appearance of ethnic comity at any cost.

For those who have stolen “the Left,” dinner-party decorum and cosmopolitan onanism were worth more than the childhoods, health, and dignity of a multitude of young girls. The reasons this evil was permitted and defended are as obvious as they are disheartening: votes, ego, ideology, power. But contempt is often overlooked as a factor. It’s evident not only in the transcripts of the grooming gangs themselves but also in the words and actions of their enablers and sanitizers. So fundamental was this breaking of the social contract that if any common human decency were left, the organizations involved would be dismantled and anyone complicit would never again hold a position of authority. This will not happen, of course. In Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” one child in a squalid cell is subjected to horrific conditions, in order to sustain a supposed utopia. In Britain, many girls were in that cell.

This contempt aligns with the progressive disdain for the Rust Belt, the yellow vests, the truckers, the farmers, the miners—for anyone who works with his hands or speaks without the approved vocabulary. It matters little that the intelligentsia depends entirely on these workers for its survival, as the Covid lockdowns made clear. The more dependent they are, the deeper their contempt. To add insult to injury, they engage in a kind of ideological stolen valor, co-opting the struggles of the marginalized, while dismissing the suffering of those who don’t fit their narrative. Last year, when a woman and her two children had a corrosive, life-altering substance thrown in their faces, the BBC saw fit to turn the news segment into a discussion of microaggressions. We assume too generously that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Noir suggests that other motivations may be at work.

What remains of the Left now lamentably operates in a Crucible-like atmosphere, where even the slightest deviation from orthodoxy invites denunciation. They claim not to believe in evil—except when it can be used as a cudgel against rivals and heretics. One of the Left’s most perceptive recent thinkers, Mark Fisher, predicted this development in “Exiting the Vampire Castle”—only to be set upon by the very puritanical forces he described, proving his point. (Fisher tragically took his own life in 2017.) The Right will blame Marxism, but the truth is more squalid. “The surest way to work up a crusade in favor of some good cause is to promise people they will have a chance of maltreating someone,” Aldous Huxley wrote. “To be able to destroy with good conscience, to be able to behave badly and call your bad behavior ‘righteous indignation’—this is the height of psychological luxury, the most delicious of moral treats.”

Noir, while acutely aware of the corruption within class systems, the state, and the elite, never reduces human behavior to politics alone. Psychology remains paramount. It may be nearly impossible to live honorably in a corrupt world, but the world is never wholly deterministic. We are afforded free will by our absent God, and, whatever the justification, every act of evil comes as a Faustian choice. Evil always seems to belong to someone else, somewhere else. “If only it were all so simple!” Solzhenitsyn countered. “If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

The devil didn’t disappear just because we stopped believing in him. And he never ceased believing in us.

Top Photo: Detail of stained-glass window, crypt of the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene, Rowington Close, Paddington, London (AP Photo)

Source link