Charles Fain Lehman, Judge Glock, Rafael Mangual, and John Sailer discuss the House tax bill, California governor Gavin Newsom’s model ordinance on homelessness, and summer vacation plans.

Audio Transcript

Charles Fain Lehman: Welcome back to the City Journal Podcast. I’m your host, Charles Fain Lehman, a fellow at the Manhattan Institute and senior editor of City Journal. Joining me on the panel this week are my colleagues, Judge Glock, economics guy at the Manhattan Institute, Ralf Mangual, crime guy at the Manhattan Institute, that makes you sound like you’re a criminal, which was a little unclear on that front still, and John Sailer, director of higher education, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, and author of an excellent series at City Journal investigating the fellow-to-faculty pipeline, which shows how radical activists get into academia. John, thanks for joining us on the panel this week.

John Sailer: Yeah, excited to be here.

Charles Fain Lehman: I want to jump right into the news and zoom in a little bit on a story that actually CJ covered earlier this week. The House tax bill rolled out and in addition to a number of other major changes, it seems likely that Congress is going to attempt to pay for its massive reduction in taxes by increasing the taxation on certain major endowments with the endowment tax expected to rise from 1.4 percent to 21 percent for certain universities. On the one hand, it’s part of the administration’s war on elite universities as we’ve talked about in the show a great deal before. But on the other hand, I think there’s been some skepticism and some pushback, most notably in the pages of the City Journal earlier this week, we got a piece from Larry Arnn, who’s the president of Hillsdale College, challenging the wisdom of the move. I want kick it first to our higher education guy, John. What do you make of hiking the endowment tax? Is this another step in the war? Is it a smart step? Is it a foolish one?

John Sailer: There are blunt force instruments and there are precision instruments that the federal government can use to try to address issues in higher education. Increasing the endowment tax would absolutely fall into that category of blunt force instrument. You know, there’s no way to target an endowment tax toward particular, you know, tie it to particular practices that universities are engaging in. What it really means in effect is just that every university that qualifies for the tax is less wealthy. Now, you can argue that maybe that’s a good thing just on the merits. Some people say that, well, the cushy endowment arrangement that universities have, well, that’s sort of a government subsidy on universities in general, and we have mistrust in universities. Ergo, why not?

I’m not particularly convinced by that. That’s sort of a different argument than I think we’re mostly engaging in right now. I see the big issue in higher education and the big mandate that reformers have as specifically addressing sort of ideological issues, the root cause of mistrust. And I think that if we can actually address those issues, address the underlying issues, then I think most Americans would actually be fine having robustly funded universities. And endowments are actually a helpful way to let universities be robustly funded without having them necessarily depend on the federal government. So in general, I’m not persuaded that this is the right step.

Rafael Mangual: Yeah, I agree. mean, look, what you don’t want to do is you don’t want to take away a tool for universities that would allow them to become less dependent on federal funding, right? And I think that’s the big thing that a lot of Americans object to is this idea that we are using taxpayer dollars to fund universities that have nothing to do with the vast majority of taxpayers. They don’t care about the vast majority of taxpayers. They would never let the vast majority of taxpayers into their schools. They’re not really offering all that much. I understand why Republicans in Congress and the administration want to sort of hurt these universities like Harvard and Columbia and Princeton in the way that they’re trying to do through this. But the problem is, as Larry Arnn point out, is, you know, it’s a pretty broad-based bill. It’s going to harm also the universities that have done the right thing. Hillsdale College purposefully does not take any federal dollars, does not take any government dollars. Why? Well, because it wants to remain independent. It never wanted to be in a position for the Obama administration or the Biden administration to be able to hold federal funding over its head and tell it what to do. That’s a good thing. It’s a thing that we should encourage. But they can’t maintain that level of independence, and schools like it can’t maintain that level of independence if they can’t count on the endowments that they’ve built through private fundraising, you know, to grow and to grow in a way that again allows them to continue to operate and offer value to conservatives across the country. I, you know, I hope, I’m glad that Larry wrote that piece and I’m, you know, I’m hopeful that Republicans in Congress will read it and understand that what they’re doing is harmful.

Charles Fain Lehman: Yeah, you know, I wonder, I think there’s probably not a fiscal responsibility argument here, right? Like the amount of money that’s raised by the endowment tax is pretty small, but it is the case that they’re packing so much that’s favorable to recently included GOP constituents into this bill. I’m thinking of like no tax on tips as the big priority. But the example of this priority that, you know, just picking somebody as an object of increased taxation to offset that, maybe is a good impulse. Judge, I’m curious, I mean, is there a fiscal sound in this argument here? What do you, what do you make of this?

Judge Glock: Not really, right. This is is peanuts compared to the trillions they’re going to effectively lose through the the new tax bill. You know, it’s as a lot of people pointed out, there’s a lot of giveaways in this bill and I do share everybody’s concerns that we shouldn’t also use the tax code to punish some particular groups we’re not fond of. So it doesn’t seem like this is a real fiscal responsibility argument. This is a “we really hate universities” argument and I’m with them. I really, really hate universities. They’re really, really not helpful. but then don’t do it through the tax code. Just stop giving them cash. We like this, this is my thing. Like with everything we got to think of the budget is a combined entity. So we have these things where like we’re shoveling cash out the door to universities through the Department of Education, through grants, etc. And then we’re trying to take away with the other hand, well, just cut out the middleman, just stop giving them money in the first place. And you can actually save on that. But I know we have questions.

Rafael Mangual: Yeah, I think part of what this is is a sort of illustration of the frustration that Republicans are feeling because they feel like all of these attempts to cut university funding are being blocked and stopped. And again, I get that. I understand the impulse. I’m sympathetic to it. But ultimately, I think this is just wrongheaded.

Judge Glock: But wait, they’re being, I mean, they’re ultimately being stopped in Congress, right? Like it’s, yes, for some of this, they’re going to need the, they’re going to need some Democrat votes in the Senate. But like the way it gets stopped is you stop funding in Congress. You get enough votes to stop sending the cash out. Yeah. Some of the particular stuff is being held up in courts, the executive action, because, there’s borderline questions about what the president can do on his lonesome without the other branch of the government. But ultimately, like, if they want to stop sending money the same way they’re adding taxes in this tax bill, they should use the other part of the Congress to stop sending the cash.

Charles Fain Lehman: So let me ask an affirmative question, and I think Judge has gotten to this, but are there other ways, if we think this is probably not the right hammer for this particular set of nails, but we do agree that there’s a lot of merit to Hillsdale argument, are there other ways to encourage universities to move in the Hillsdale direction? As Ralph alluded to, Hillsdale doesn’t take federal funds, it’s so they can avoid a lot of oversight. I think that is a much more attractive package to more mainstream universities, more leftist universities really, than it was three years ago. Are there ways we can push them to embrace that in a way that ultimately promotes educational pluralism?

John Sailer: So I would say that one issue you run into when you’re talking about universities that are not set up like Hillsdale, which is, you know, it’s a robust university, but it’s not like a scientific research-heavy university at all, is that a lot of the federal funding for universities comes through scientific funding and a lot of the science that happens in the United States through universities simply would not happen if it were not for the federal government. Or at least there would be kind of, it would require some massive changes that would take time and be extremely disruptive.

Just to give like an example, the largest funder, the largest private foundation funder of the sciences is the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Its endowment is about $24 billion. That is about, or that is half the NIH’s annual budget. The NIH just dwarfs what the Howard Hughes Medical Institute does. And so it’s going to be very difficult to get these universities to say that we’re just going to totally drop what the federal government has to offer. And it’s going to be very difficult to get the federal government not to do that. But I do think the promising path for reducing just the amount of federal cash going into universities is through student loan reform. And I think that that’s a place where there’s like a growing consensus that, yeah, we’ve got this problem.

We also have a problem where just too many students are being encouraged to go to college in a way that doesn’t pay off and probably causes some of the downstream problems that we’re seeing. And so I think that like, if you want to narrowly target a problem and solve this issue of just cash flowing in the wrong way, student loans is the way to go.

Rafael Mangual: I know it’s kind of crazy to suggest that the government consider curtailing its own power, but why hasn’t anyone floated the idea of a law prohibiting the government from attaching these kinds of strings to scientific funding? Why not just depoliticize that particular endeavor? If we agree that there’s value in the federal government using its vast resources to fund scientific research that can’t happen in other institutions,

Charles Fain Lehman: What’s scientific research? Right? I mean, that’s the, the core problem there is, you know, when any definition becomes a target, it ceases to be, or any measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a useful measure. And so I think the answer is, is interpretive intersectional dance a science? Well, it depends who qualifies it. According to whom?

Judge Glock: I mean, it depends, there’s a person, there used to be a person in NIH or NSF or the Department of Education. Wait, we’re supposed to spell everything out, National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation and Department of Education whose job was to look at these grants and make sure you weren’t, you know, looking at transgender mice or whatever. You were looking at something that actually had a real impact.

And that person has either not been doing their job or been funding the transgender mice stuff. They can do that transgender mice stuff. You can do that. You can. I’m sure there’s transgender rice stuff too. But you can do that and ask like, hey, we are funding this. We are funding this particular piece of cancer research in two years. We’ll check back in with you. If you haven’t cured 10 percent of cancers yet, you’re not getting the grant again. And they clearly have not been doing that. Hopefully the Trump administration can do that when they’re giving out the grants in the future.

Charles Fain Lehman: All right, I want to take us out. So I want to ask the panel very briefly to predict the future as per usual so that we’ll be held accountable for our views.

Rafael Mangual: We get held accountable for this stuff?

Charles Fain Lehman: Yeah, no, this actually determines your continued employment on this podcast. If you’re wrong, you’re gone. This is an accuracy podcast. So yeah, here’s the question. In let’s say five years, are there going to be more colleges, meaningfully more universities that follow Hillsdale model, that withdraw themselves from received federal funds? Ralph, you’re shaking your head. What do think? No?

Rafael Mangual: No, no, it’s just too, I mean, it’s just too valued. Look how Harvard is fighting with the $53 billion endowment and they are fighting tooth and nail. It just means too much to them.

Charles Fain Lehman: Fair. Okay. Judge, what’s, what do you think?

Judge Glock: No, it’s like John says, the students loans is for most of them. I mean, Harvard really, the other big dogs don’t care so much. But for most of the colleges, everything’s student loans and without that you can’t do anything. Hillsdale’s sitting on a pretty pretty endowment. So they’re the exception, but so it goes. The government should stop doing that’s the answer, of course.

Charles Fain Lehman: Fair, okay, John, what’s your take? More Hillsdale’s?

John Sailer: Yeah, I have to agree. I don’t think that’s in the cards. And I think that, you know, even if we get serious reform on federal funding for higher education, I don’t think we go to zero ever. And I think universities are far too dependent on it. We will sooner see a lot of closures, which I think is in the cards, but probably more for low performing non-elite universities, probably, I would be comfortable wagering that we’re going to see probably zero follow the Hillsdale model unless they’re forced to, unless the Department of Education just says no more money.

Rafael Mangual: Right. Yeah.

Charles Fain Lehman: Our producer Isabella is in the chat. She’s a Hillsdale alum. She’s voting for more. I actually have to agree with her. I think we’re going to see a couple. I think that enough schools are going to be scared by the recognition that actually Republicans are finally coming to play. Some of this is contingent on how successful they are on pulling Harvard’s funding or how successful they are at pulling Columbia’s funding. But I think you could see a small, well-endowed liberal arts very progressive schools say we aren’t going to be involved in the federal government anymore because you know next time around President Vance is going to come and deny our right to do intersectional dance studies and that’s a core part of our brand identity.

Rafael Mangual: I think they’ll forget all about that when it’s President AOC.

Charles Fain Lehman: Maybe, maybe, maybe. You know, Hillsdale’s been around for a long time. They’ve got the, they got the, there are others, Wyoming Catholic, Grove City, there are schools who do it. They’re mostly “right wing,” quote unquote, but they do it.

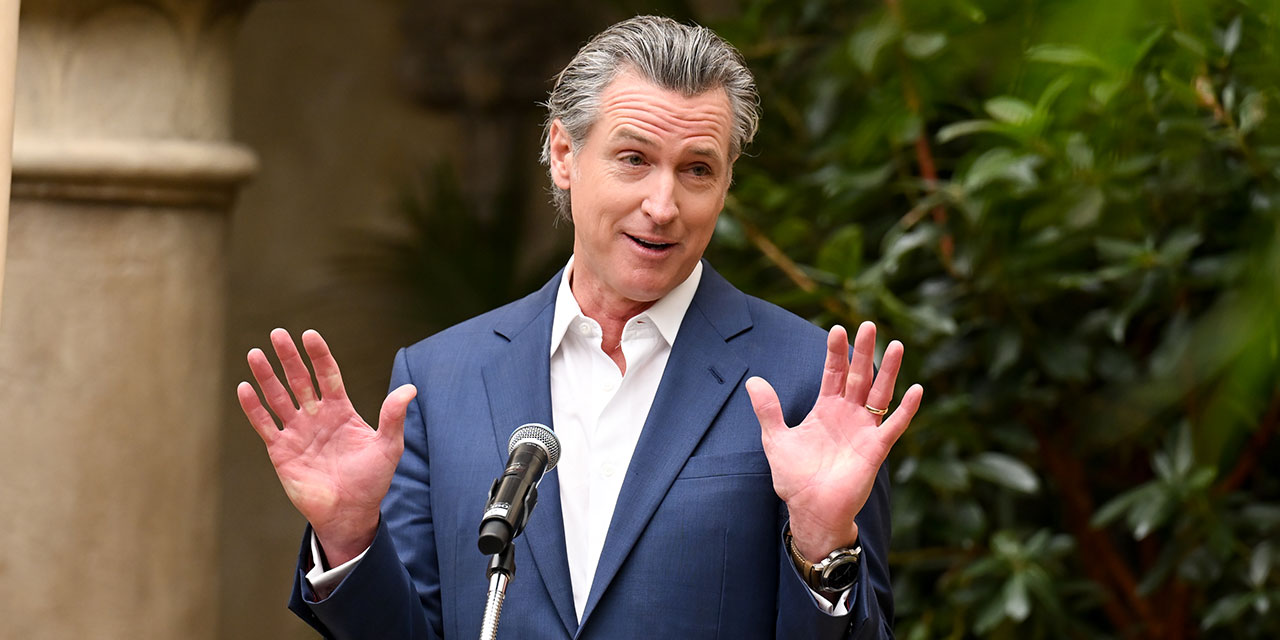

All right. I want to talk about the other news of the day. Earlier this week, California governor Gavin Newsom released a model ordinance banning homeless encampments in the state that is designed to tell cities how to ban encampments in the state and called on California municipalities to adopt it. It comes as the governor steps up his efforts to deal with California’s Titanic unsheltered homelessness problem, which is, you know, Judge, I’ll ask you to come in on this talk about the scale of the problem a little bit, but easily the worst in the nation. So I want to talk a little bit about the policy, but also the politics of it, because it’s a real about face.

Judge, let me ask you to sort of read our listeners in on what’s been going on with homelessness in California over the past decade.

Judge Glock: Yeah, so if our listeners have never, looked at the news, the internet, or social media, they might be unaware that apparently California, has a real big problem with, with homelessness. but, but for all the horror shots you see and what now has become like B-roll footage on every news, program in the country, whenever they do this, the, long drive, videos of going through the Tenderloin in San Francisco or Skid Row in Los Angeles.

Uh, it’s really, the stats bear this out. It is really, really bad. Uh, by some measures, California has about half of all the unsheltered homeless in the nation. So this is a state, a little more than 10 percent of the US population. But if you’re looking at a homeless person outside of a shelter, out on the street, uh, more likely than that, that person is in California. Uh, and they still have also a big problem, of course, with, uh, a large number of people in shelters. And that’s overwhelmingly concentrated, especially in LA. LA on its lonesome has around 20 percent of all the unsheltered in the country. So it’s really, really bad there. It’s getting worse. I saw a recent post by a Governor Gavin Newsom that said, California is leading the way and slowing the increase in homelessness. Where they were bragging that, listen, our increase in homelessness has been going down. We’re on the second derivative here. We’re like, we’re growing homelessness more slowly than it used to be. It’s still getting worse, but just not, it’s not getting worse as fast as it used to be. So yeah, at least he’s trying to, at least this is a start. We can talk more about it. It’s not a good start. I’ve read through the actual thing he’s proposing, but it’s something.

Charles Fain Lehman: Yeah, Ralph, let me invite you to comment on this.

Rafael Mangual: I mean, you know, look at it. I like that he is trying to moderate in so far as it communicates that, you know, high level Democrats are reading the signal and the signal from the American public is we’re tired of this stuff. We don’t want to see it anymore. We want something done. Great. But do we really think that a model ordinance is communicating the kind of, I mean, like, why not just task the LAPD and the LA sheriffs and the San Francisco PD who are clearing these encampments and taking people off the street and prosecuting them for using drugs out in the open and doing all the things that we know would help reestablish order much more quickly. And I think the answer to that question is because they don’t actually have the stomach for this, right? Like, people like Gavin Newsom are just experts in marketing, right? Like it is how can I brand myself in a way that aligns with the political winds? This is nothing more than an effort to do that. I don’t think there’s going to be any real substance to it. I don’t think there’s going to be any downward pressure from the California governor to force municipalities to adopt this. And frankly, to the extent that municipalities do adopt it.

It doesn’t mean that the homeless population can’t move over the county line in one direction or another. you know. So, yeah, I’m just, I’m very skeptical that this is actually going to do anything worthwhile. But, you know, I do think that conservatives should take the win insofar as like they’re getting prominent Democrats to admit that this has been a problem.

Judge Glock: Yeah, I mean, just to add on this too, if you look at the model bill, it notes that it shall be unlawful to camp in X, Y and Z places and set up a tent. And then it also says it shall be unlawful to camp after we put a sign up saying you can’t camp. But then you think, wait a second, it was already supposed to be unlawful before you put the sign up. But then the most surprising thing to me about Newsom’s model is it just says it’ll be unlawful. There’s no penalty.

There’s no like, there’s no misdemeanor or we’ll charge you or give you even a ticket or ask you to pay something or do community service. It just says we would like you not to do this. So ultimately this is classic Newsom. He’s claiming, “Hey, I’m going to look tough.” Last year he put on some designer jeans and like threw some soiled mattresses and a dumpster to show how he was taken on the homeless crisis. This time he released his ordinance that we’re going to make it unlawful. We’re going look tough. No, you actually can’t arrest or fine anybody. So what does this amount to? It’s saying you can remove their junk off the sidewalks, which you could before and you should do, but that’s it. They’re not actually making it illegal.

John Sailer: Yeah, you know, it’s interesting whenever somebody is positioning themselves to run for president, obviously they have to please their primary constituency and a general constituency at the same time. So you have to learn to sort of code switch in all of your, you know, your symbolic policy actions. And Newsom has been doing this in very clever ways by making, you know, statements that seem more moderate, at the same time, you know, I think he’s going to be able to continue to appeal to his, you know, primary constituency fairly well. I think that if he wants to brandish his progressive credentials, he’s going to be able to do that, he’s going to be able to point to various ways that he’s promoted social justice, and at the same time, what’s particularly funny about this policy is that it’s not a policy at all, it’s a model ordinance, which means that if it’s not adopted, on one hand he can say that I did it, I did it, I went out and tried to, and you know, finally got tough on homelessness, but at the same time, if absolutely nothing happens, and if he doesn’t want to fight a political battle with people throughout his state, progressives throughout his state. He can just say, they tied my hands. They didn’t listen to me. And he has the ability to kind of play both sides. And I actually just honestly think that nobody’s going to buy that. I think that Gavin Newson’s strategy will not work.

Rafael Mangual: That is exactly the right thing to key in on, right? Like, he doesn’t actually want to have the political battle because he knows he would lose it, right? If he went out on a limb and demanded that his state legislature create a law along those lines, pass it, he knows that the progressives in his party are never going to go for that, and then he’s going to look weak and he can’t afford to do that. So this is as far as he can go. So not only is it an acknowledgement that, you know, his side of the aisle has been too soft on this, but it’s also an implicit acknowledgement that they’re still too soft on this. The Democrats still cannot be trusted to actually take meaningful action in this space because if he believed that it was possible, he would have done this through the legislature and made it state law. And he would have used his political capital to do that. But he knows that that’s just a guaranteed out and he doesn’t want to take it.

Charles Fain Lehman: Yeah, I think there is this very interesting to me dynamic where I’ve said this in a, I forget if I said this last week. I’ve been in like three or four different conversations over the past couple of weeks and I would characterize the center left context, some of the public, some of the private, where everyone’s sort of agreed with me that public disorder is an issue and everyone goes, yes, this is very serious issue, people feel afraid, we need to do something about this. And then we retreat almost immediately into sort of talking about preventative efforts and housing and mental health care and what really is disorder anyway. And I think there is a still at a level of ideology and rhetoric an unwillingness or inability to say, “these behaviors are antisocial and it’s with the legitimate function of government to enforce the public’s desire not to have to put up with antisocial behavior.” That like actually it is unfair to take over the street and camp on it so that nobody else can use it. It’s unfair to exclude other people from public space by sleeping in public. And it’s right and just that state and local governments enforce laws that prohibit that behavior. And so, know, I think we’re going to continue to struggle with these issues to the extent of the policymakers or anything at all because these cities are still run by people who are unable to say to themselves “there is a normative justification for these policies that everyone wants me to implement.”

Rafael Mangual: Not only are they unwilling to say that there’s a normative justification, but they simply don’t have the stomach for what enforcement actually looks like. I mean with any set of rules that you have, you have to have an answer to the question “or what?”. Right? You can make a rule, you can’t do X, Y, and Z. Okay, you have the rule. Someone does X, Y, and Z at the same time and you say, hey, you can’t do that. And they say, what are you going to do about it? I’m not stopping. So we have to stop. Well, I’m not stopping. If I don’t stop, what happens? And what should happen is that the police should come, put you in handcuffs, and take you to jail.

But Democrats have shown over the years that they simply don’t have the stomach for that, which is one of the reasons why, as Judge pointed out, there is no enforcement mechanism in this model. And that’s really at the core of this. They don’t have the stomach for doing the ugly thing. They don’t want to create the conditions for an interaction in which some homeless person decides to resist a police command to clear, and then they put hands on them and then it gets ugly and maybe there’s a, you know, a deadly use of force or something like that. They don’t want to create the conditions in which the enforcement arm of the state has to come and actually do its job because they don’t have the stomach for that. And I think a lot of them are also just ideologically opposed to that, right? There are a lot of people in the California State Legislature and in the city councils of the various cities throughout that state that believe in prison abolition, believe in defunding the police, believe in using all law enforcement dollars and taking them away from the cops and putting them towards various social welfare programs because that’s what they think is at the root of criminal offending. So ultimately, like I said, I think what this is Gavin Newsom just realizing that he is in a party of crazy people and he’s trying very, very hard not to disturb them and draw their ire.

Charles Fain Lehman: John, let me give you the last, let me give John the last thought and then we get to exit.

Judge Glock: Okay

John Sailer: Well, I think it’s pretty rich that that dynamic that you were describing is kind of playing out at two levels. So Gavin Newsom refuses to actually enforce, because it’s just a model ordinance, an ordinance that would refuse to actually, that would have no consequence and thus refuse to actually enforce the problem that he’s trying to address. It’s sort of a doubly throwing your hands in the air and saying, we want to solve this problem, but we’re not going to do anything.

Judge Glock: Charles, let me say this last thing, because the one, the one consensus I think they agree on is like, okay, you can’t put a bunch of junk in the middle of the sidewalk to block egress and ingress and all of that, partially because the disabled have made a correct stink about them being able to get around on city sidewalks. And two, like even if you think the homeless have a right to be somewhere in public space and you can’t do anything about it, do they need that much stuff?

And I say only in America is one of the biggest problems with homelessness, too much stuff around. Like there’s just too much material possessions to have that you have to clear. And even Newsom, think is like, okay, we can move a bunch of the junk out. And that’s something.

Charles Fain Lehman: Yeah, all right, all right, I want to ask very briefly yes or no, synthetically, not just attributable to this, but generally in five years time, say, is California’s homelessness problem going to be meaningfully improved? Is it going to be better, is it going to be worse, is it going to be the same? Judge, we’ll get to you last. John, what’s your take?

John Sailer: The only improvement that I would bet on is that there will be more of a consensus that this is a problem. I think that people being fed up, that’s going to increase. And so, will that be enough to fix it in five years? No, but I think directionally, that’s probably where things will eventually go.

Charles Fain Lehman: Alright, Ralph.

Rafael Mangual: I’m going to say, I don’t know, it depends on how you define “meaningfully,” but I think maybe yes. And the reason I say that is because, you know, the last election cycle, things were, winds were blowing in a very different direction in California. You had, you know, Sheng Thao recalled, you had Pamela Price recalled. A couple years before that, had, you know, Chesa Boudin recalled. You had, you know, what’s his name in California, Gascon lose his reelection bid and Nate Hochman went, you know, Prop 36. I don’t know, the voting public does seem to be growing increasingly fed up and they might actually do something about it in the way of local elections and that might just totally change the dynamic on the ground and in the legislature. So I’m going to express some hope.

Charles Fain Lehman: All right, Judge, what do you think? You’re an optimist? Since when?

Judge Glock: I’m with Ralph here, like homelessness used to… yeah, it happens. So, homelessness used to be this weird niche issue that most people didn’t care about, but by several polls is the number one public issue in California, and you know where people stand on which side of that issue, is that they need enforcement, they need to move people off the streets, and to assume that the political class in California can indefinitely ignore the overwhelming feeling of the public on the number one political issue in the state indefinitely, not going to happen. Sooner later, there’s going to be a revolt, a referendum. Somebody is going to come up through the party to say, I’m going to have to take care of it. As you say, in the local level, people are already doing it, like Daniel Lurie, new mayor of San Francisco. So I think sooner or later, like people, the public’s will is going to be expressed.

Charles Fain Lehman: You know, I’m really 50-50, which is to say, I think there’s still an ideological block. There’s an inability of progressive leaders to be able to say, this is a problem to which we can not only articulate a solution, but can justify that solution to ourselves. We feel that it is normatively acceptable for us to engage in. Because the solutions are not hard. It’s not hard to deal with unsheltered homelessness and public camping. We know how to do it. It’s just like, are you willing, as Ralph puts it, are you willing to stomach it? And I’m not sure they will be, so I might be in John’s camp.

All right, before we go, I want to take us out. Our friends at the New York Post reported the first great white shark of the season has been spotted gliding through clear Montauk waters. Everybody keep your eyes out for the great whites. But in the meantime, I want to ask all of our panelists, what are your plans for summer vacation? Judge, where are you headed this summer?

Judge Glock: I guess with the shark announcement to like my kiddie pool, and I’ll dip my feet in there or something. I don’t like sharks. That’s all I’ll say.

Charles Fain Lehman: Okay, Judge is down on sharks. John, where you on sharks?

John Sailer: Well, it’s appropriate that we spend some time talking about Gavin Newsom because every summer I end up spending a lot of time in California where my wife’s family lives. So I’ll be in California. Fortunately, I’ll be in the farmland. So I don’t think I’ll run into much of the encampment issue.

Charles Fain Lehman: What about the California land sharks? You got to watch out for them. Ralph, Long Island sharks, you got to be worried.

Rafael Mangual: Luckily for me, I still can’t afford the Hamptons, so, you know, not too worried about it, but my wife and I are celebrating our 10th wedding anniversary this summer with a nice little vacation to the Caribbean, so I’m looking forward to that.

Charles Fain Lehman: Your ability to afford the Hamptons is contingent on your accuracy bonus for your predictions on the City Journal podcast. So let’s see, let’s see how you’re doing on that front. We’ll figure it out. As for me, I will be spending the summer mostly here. I think we’re going on a little trip to Baltimore. Very exciting. We’ll take my kid to a hotel cause he’s like fixated on hotels for some reason, like a four year old is. And of course I will be spending this time listening to the City Journal Podcast.

Speaking of listening to the City Journal Podcast, that’s about all the time we have. Thank you, as always, to our panelists and to our producer, Isabella Redjai. Listeners, if you enjoyed the podcast, or even if you didn’t, please don’t forget to like, subscribe, ring the bell for updates on YouTube or wherever you get your podcast content. Feel free, if you’re listening on YouTube, to leave comments and questions down below. At some point, we might even answer some of them. We’ll see if we get enough questions.

Until next time, you’ve been listening to the City Journal Podcast. We hope you’ll join us again soon.

Photo by Michael Buckner/Variety via Getty Images