The goal of New York State’s Responsible AI Safety and Education (RAISE) Act—protecting people from AI harms—is admirable. But by assuming that AI models themselves are the key leverage point for ensuring safety, RAISE risks turning a technical challenge into a bureaucratic burden.

Authored by State Assemblymember Alex Bores, the RAISE Act applies a list of requirements meant to ensure that AI technologies get deployed and are used in a responsible manner. It is currently being debated in committee. Bores and other legislators across the country are concerned that advanced AI could help create chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. However, the real risks lie in the accessibility of dangerous precursor materials, not the AI systems themselves.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Like California’s SB 1047, the RAISE Act targets advanced “frontier models”—AI systems that meet certain computational thresholds and cost $100 million or more to train. The rules also extend to other models built on top of these covered systems.

Model developers covered by RAISE must follow, among other rules, mandated testing procedures and risk mitigation strategies; undergo regular third-party audits; submit to transparency requirements; report instances where a system has enabled dangerous incidents; retain detailed testing records for five years; perform annual protocol reviews and updates; avoid deploying “unreasonably” risky models (a legal term of art); and protect employee whistleblower protections. All of the requirements are backed by significant penalties for violations. Penalties start at 5 percent of compute costs for a first violation and rise to 15 percent for subsequent ones, so firms could face fines of $5 million to $15 million.

On paper, the bill seeks to align incentives between the profit motives of companies and public safety interests. As Bores wrote, “Limited to only a small set of very severe risks, the RAISE act will not require many changes from what the vast majority of Al companies are currently doing; instead, it will simply ensure that no company has an economic incentive to cut corners or abandon its safety plan.”

In practice, aligning models to stop misuse has proven difficult. That’s because model alignment seems to be most useful in preventing accidental harms such as generating bad advice or producing factually incorrect information, not in stopping malicious actors who want to build bombs. Princeton University computer scientists Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor, who have written a book about these problems, call it “model brittleness.” As they write, “Even if models themselves can somehow be made ‘safe,’ they can easily be used for malicious purposes.”

Even more importantly, cutting-edge approaches now focus on external systems operating on top of models to maintain alignment. Leading companies are developing external content filters, human oversight protocols, and real-time monitoring systems that can detect and prevent harmful outputs. In other words, the market is already outpacing the regulatory framework.

RAISE imposes a heavy set of requirements to achieve its goals. For instance, if robust safety protocols are in place and working effectively, why mandate five years of record-keeping? Similarly, if a model passes an independent audit certifying compliance with those protocols, why must developers still meet a separate “reasonableness” standard for deployment? Either the audit is thorough enough to flag unreasonable risks or it isn’t.

These contradictions go beyond bureaucratic inefficiency. The RAISE Act attempts to tackle corporate transparency, employee protections, technical safety, and liability—all within a single regulatory framework. The result risks prioritizing compliance over actual safety outcomes.

Policymakers and advocates for AI safety legislation tend to downplay compliance costs, but they shouldn’t be so dismissive. In previous work estimating the compliance costs of AI bills, I found that “official projections may be overly optimistic” and the real price for compliance might in fact be much higher. For that project, I compared official cost estimates from three AI bills with estimates from leading Large Language Models (LLMs), finding that the LLMs often projected similar figures to the baseline, but with higher ongoing costs.

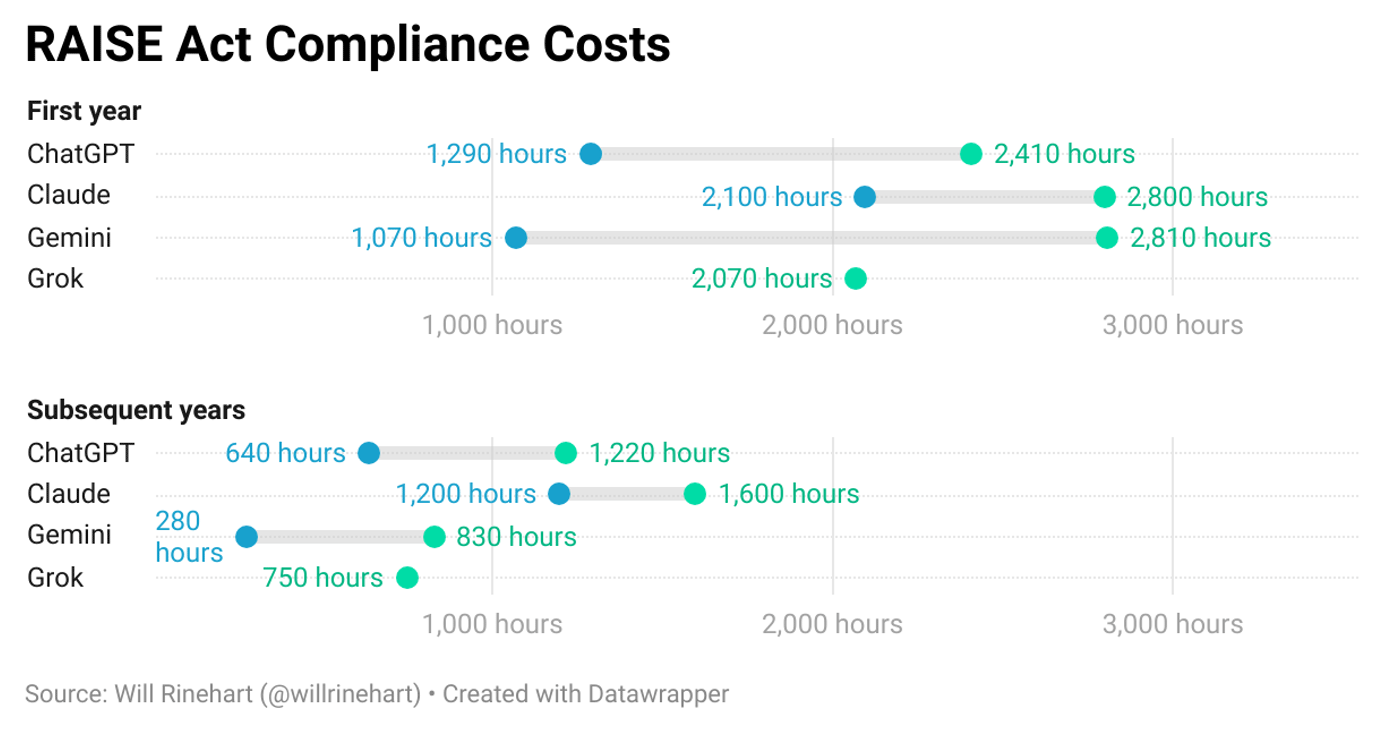

Using a similar method, I asked the leading LLMs to read the RAISE Act and estimate the hours needed to comply with the law in the first year and in every year after that for a frontier model company. The results, displayed in the table below, suggest that initial compliance might fall between 1,070 and 2,810 hours—effectively requiring a full-time employee. For subsequent years, however, the ongoing burden was projected to be substantially lower across all models, ranging from 280 to 1,600 hours annually.

The wide range in estimates underscores the fundamental uncertainty with the RAISE Act and other similar bills. The fact that sophisticated AI models are not converging on consistent compliance costs suggests just how unpredictable this legislation could prove in practice. The market is moving quickly. We need laws that prioritize effective risk mitigation over regulatory theater.

Photo by Lori Van Buren/Albany Times Union via Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link