In the early twentieth century, New York law recognized suicide as a “grave public wrong” and declared attempted suicide a felony. Last week, the State Senate passed a bill that would effectively recognize suicide as a human right.

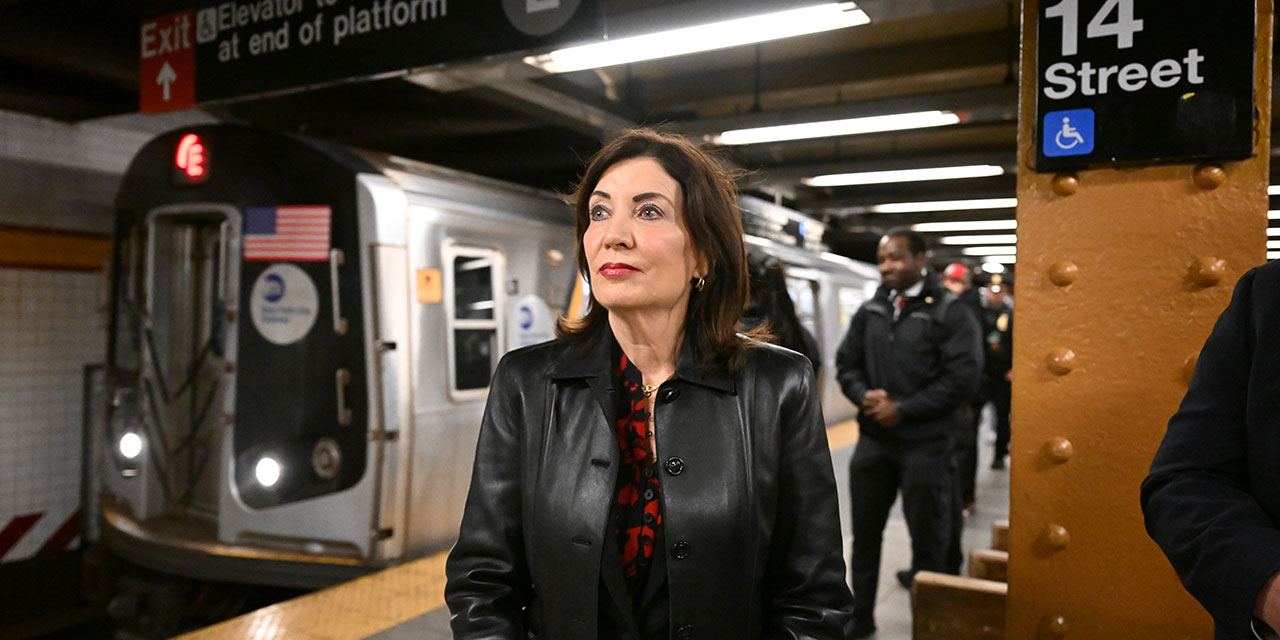

The Medical Aid in Dying Act, which passed the State Assembly in April, would allow people diagnosed with terminal illnesses to request a prescription for lethal drugs. Governor Kathy Hochul should veto the measure, which, if passed, would signal the Empire State’s further abandonment of vulnerable citizens.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The bill has relatively few safeguards. While it requires that two physicians affirm the judgment that a person’s condition gives him six months or less to live, it does not require that the person requesting the drugs be psychiatrically evaluated. As John Ketcham notes, it also fails to outline a mechanism for recovering the poison from a person who requests but ultimately declines to use it. And the bill’s drafters declined to include a residency requirement, meaning qualified citizens from any of the 37 states that forbid assisted suicide would legally be able to travel to New York to be euthanized.

The title of New York’s bill mirrors that of Canada’s assisted-suicide law. The Canadian law, which at first also applied only to the terminally ill, shows how quickly even limited permissions for assisted death expand to other vulnerable populations.

In 2016, Canada’s supreme court invalidated a national law that criminalized assisted suicide. In response to that ruling, the Parliament drafted legislation allowing only those whose deaths were “reasonably foreseeable” to elect euthanasia. The Superior Court of Quebec later declared that law unconstitutional since it violated the country’s “right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination.”

The government didn’t challenge the ruling. That prompted the legislature in 2021 to pass Bill C-7, which repealed the terminal-illness requirement and allowed anyone with a physical condition to elect suicide, subject to some feeble safeguards. That same year, more than 200 people in Canada without a terminal illness killed themselves through the country’s MAID program. By 2022, dystopian stories emerged of poor and disabled people being coerced to consider suicide.

These supposed “excesses” of Canada’s euthanasia program were the inevitable result of its supreme court’s ruling that at least some people have a right to commit suicide. As Ross Douthat observes, once a state concedes that suicide is a legitimate response to some forms of suffering, but not others, people will inevitably challenge the threshold that the state defines. A terminal illness can cause terrible pain for a time, but severe chronic illnesses can cause intense suffering spread over decades. Whose pain is worse? In any case, why don’t both “deserve” to have their suffering alleviated?

In New York, proponents of assisted suicide have framed their cause as a matter of human rights. State Senator Jessica Scarcella-Spanton argues that the euthanasia bill “affirms New Yorkers’ right to make deeply personal end-of-life decisions.” Assemblyman Amy Paulin insists that it gives “terminally ill New Yorkers the autonomy and dignity they deserve at life’s end.” The New York Times reports that State Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal, one of the bill’s sponsors, has described it as “a statement of New York’s values” and a rejection of Republican efforts to “increase governmental control over people’s bodies.”

Those who oppose assisted suicide in New York will have to address these arguments directly. Do people have a right to commit suicide? Does the government have a right to “control” the “bodies” of people who intend to do to themselves irrevocable harm? Should the bill be opposed because it creates a slippery slope, or should it be opposed because no one—including the terminally ill—should be able to take his own life?

Human life is marked by terrible suffering. Some children are born with debilitating diseases, live in constant pain and dependence, and die having never experienced many basic joys of life. Some men who knew strength and vigor are crippled in car accidents and forced to spend aching decades in wheelchairs with full knowledge of what they’ve lost. Cancer and other diseases in their terminal stages impose on people pain and anguish that even modern medicine fails to relieve.

But once the state decides that anyone, on account of illness, has the “right” to kill himself, it has decided that suffering can render life worthless. More fundamentally, it has accepted a mistaken view of autonomy, which posits that people have the right to harm themselves—a view that New York and every state rejects when they involuntarily hospitalize a suicidal teenager.

New York was right in 1909 to declare suicide a “grave public wrong.” Governor Hochul should veto a bill that would enshrine its opposite in law.

Photo by NDZ/Star Max/GC Images via Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link