Surprise and delight were the common responses to the announcement that this past week Pope Leo XIV approved the proposal of the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints that St. John Henry Cardinal Newman be named a Doctor of the Church.

What most Americans know of Newman, if they know anything at all, is through the “Newman Centers” which bear his name on secular college campuses. On the other hand, I had the good fortune to be introduced to Newman as a boy of eight or nine by my father, who, although a high school graduate and common laborer, was a self-taught man in matters theological and philosophical. As he devoured Chesterton and Belloc—and yes, Newman—I would sit on his lap and ask questions about these “greats” of the Anglophone Catholic intellectual tradition.

That said, where does one start and finish with someone as multi-talented and accomplished as Newman?

From Evangelical Anglican to full communion with Rome

John Henry, the first of six children, was born into an Evangelical Anglican (that is to say, “Low Church”) family on February 21, 1801. At the age of fifteen, he perceived the importance of a “definite creed” and a vocation (probably as a missionary and also as a celibate)—not a very common path in the Anglicanism of his day. Having completed his secondary education at the illustrious Ealing, at sixteen, he began his academic career at Oxford University (which became the love of his life), where he experienced a crushing academic defeat initially, but from which he bounced back, eventually becoming an Oxford don.

Newman’s understanding of education was that information and formation made for a unified whole, with “personal influence” being extremely important. His “personal influence” was indeed very powerful, and not a few of his colleagues resented it, resulting in their move to marginalize him by insisting that a don’s function be reduced to the academic; this Newman could not accept, and he resigned his professorship.

He did, however, retain his role as vicar of the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin, from whose pulpit he captivated an entire generation. The power of his preaching did not come from rhetorical flourishes; in fact, most of his listeners acknowledged that he tended to preach in a monotone voice. Rather, it was the depth of his content, the sincerity of his delivery, and the feeling that Newman was speaking directly “to me.” We are fortunate to have preserved for us hundreds of his sermons, which were exceedingly long discourses on various biblical passages, doctrines, and controversies of the day.

His first visit to Italy occurred in 1832, traveling at the invitation of Hurrell Froude and his father; it was his first exposure to Catholicism as a cultural phenomenon. He was repulsed by what he considered to be the superstitious nature of the Sicilians, yet he felt mysteriously attracted by their devotion and piety. While on that journey, he fell deathly ill and was cared for by his Italian factotum; the kindness and concern of the man did much to help Newman overcome his earlier negative impression of Italian Catholicism (not unlike the experience the future Mother Seton had in Italy as her husband was dying and was cared for with tenderness and devotion by their Italian hosts).

It was from this very trip that many of Newman’s poems emerged. Some are quite good; others, mediocre. Perhaps the most famous of the batch is his “Pillar of Cloud” (more popularly known as “Lead, Kindly Light”).

While Newman was well known through his teaching at Oxford and his preaching at St. Mary’s, he became truly famous through his involvement with the Oxford Movement, which sought to return to the Anglican Communion many of the lost elements of Catholicism. Its members looked in particular to the Fathers of the Church and the witness of the Undivided Church of the first millennium. Although Newman had a deep reverence for much of the Catholic Tradition, he was still heavily influenced by the anti-Catholicism (anti-Romanism was how it was usually described) of his life experience and of the era.

And so, we could say, he wanted to “have his cake and eat it” as he carved out what he termed a Via Media–a middle ground between radical Protestantism and Roman Catholicism. As he studied his way into the Church, he realized that if the Early Church existed anywhere at his time, it was precisely in the Church of Rome. As a man of intellectual honesty and integrity, he declared his “middle way” to be “pulverized.” While leading many others into the Church, he himself remained outside her visible bounds for as long as possible.

Why? Because, as a very sensitive soul, with a high sense of responsibility for the souls committed to his care, he was concerned that those who had not yet “swum the Tiber” would lack the needed spiritual guidance. Eventually, however, his commitment to the truth forced him to resign his pastoral office within Anglicanism; his final sermon, “The Parting of Friends,” preached on September 25, 1843, is one of the most gut-wrenching, heart-rending sermons ever delivered. Although he treasured friendship, he valued truth even more. As he concluded his farewell sermon, he laid his preaching stole woefully on the altar and left the church.

Finally, on October 9, 1845, in the chapel of the quasi-monastery he had set up in Littlemore, he made his submission to the Church of Rome, as well as a two-day general confession to the Italian Passionist, Blessed Dominic Barberi. The description of the circumstances under which Barberi wended his way to Littlemore and the high drama of the conversion event itself would make for the stuff of a Gothic novel. Barberi himself is a study in the ways of Providence: He had a youthful apprehension of going to England as a missionary, although he didn’t even know where England was and didn’t know a word of English!

Ordination, controversy, and founding of the Oratory

Once a Catholic, Newman was sent to Rome to make final theological preparations for priestly ordination. That time also gave him the opportunity to determine what type of priestly life he wished to live. He immediately discounted the diocesan priesthood for many reasons; he was equally disinclined toward various religious orders of priests (including the Redemptorists and Jesuits, both of whom he considered to be too rigid for his personality). It was Bishop Nicholas Wiseman who suggested he consider the Congregation of the Oratory, founded by St. Philip Neri in the sixteenth century to re-evangelize Rome. The Oratorian mode of priesthood is, interestingly enough, what I jokingly refer to as “religious life lite,” a kind of via media of its own: secular clergy, living a common life, but without vows or promises. This suited Newman to a tee, especially as it envisioned men sharing a deep personal friendship, along with a common vision of Church and ministry. And thus was the Oratory brought to England.

If anyone should think that Newman’s life now would be one triumph after another, he would be most mistaken. Mistrusted in Anglicanism as a crypto-Catholic, now he was mistrusted in Catholicism by many as a Protestant mole. He was given several charges by bishops and then had many of them unceremoniously taken away from him or just simply dropped without notice. He suffered through the machinations of dishonorable people, who had him delated to Rome for heresy, without his knowledge or ability to respond. His sense of Christian hospitality and priestly fraternity had him invite the fellow convert, Father Frederick Faber, to join the Oratorian community, which ended as a total debacle since the two men were as different as night and day, epitomizing the aphorism, “no good deed goes unpunished.”

With the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in England, anti-Catholic sentiment rose to a fever pitch in many quarters; one purveyor of this was Giacinto Achilli, a Dominican friar defrocked due to his scandalous life of lechery, including the rape of many girls and the impregnation of many as well. Having been expelled from the priesthood, Achilli made a cottage industry of a lecture circuit of diatribes against the Catholic Church and her priesthood.

In 1851, Newman took Achilli and his accusations head-on in one of his lectures, resulting in libel charges being brought against Newman by the disgraced former cleric. The trial was a complete farce and a miscarriage of justice, with Newman judged guilty; he was spared prison time but fined the equivalent of nearly two million dollars in today’s money! A worldwide appeal for financial assistance went out on Newman’s behalf. To his astonishment and edification, the money for his fine was raised; he was particularly impressed with the generosity of Catholics in America, especially since most of us at that time were near-penniless immigrants. He said that, for the first time since his conversion six years earlier, he had felt at a very deep level what it meant to belong to and to be loved by the Universal Church.

As a lifelong teacher, it was natural that Newman would bring that love for education into play as a Catholic, causing Cardinal Paul Cullen of Dublin to seek his assistance in the founding of a Catholic university for Ireland in 1851. Always to the ready to put his gifts at the service of the Church, Newman undertook the project with gusto and, in his inimitable fashion, began by offering a series of lectures on how he envisioned higher education in general and Catholic higher education in particular (Newman wanted this new institution to be a Catholic Oxford); eventually, these lectures were collected into a volume as Idea of a University. Cullen and Newman were both fine men; however, their visions of education were miles apart, so that Newman would resign in 1857 and the University itself would collapse shortly thereafter. The enduring result, however, was the gift to the Church and the world-at-large of the book, Idea of a University.

In 1859, Newman turned his attention to the founding of The Oratory School, which he hoped would become a Catholic Eton. Not only was the endeavor a major success, but it became the apple of his eye as he wrote Latin plays for the students to perform, prepared them for their state examinations, played second fiddle in the school’s orchestra (!), and was a constant presence for the boys, even as a cardinal. The school’s list of famous alumni reads like a “Who’s Who” of English Catholicism, including J.R.R. Tolkien’s sons, Christopher and Michael, as well as Hilaire Belloc. An interesting historical tidbit: Tolkien began writing his Trilogy in one of the salons of the school.

Tribulations and vindication

Newman was always reluctant to discuss his conversion, largely due to his dislike for attracting attention to himself, but also since he did not want to fan the flames of anti-Catholicism any further. However, he was forced to address the issue in his 1864 spiritual autobiography, Apologia pro Vita Sua, due to a hateful attack on him in the press by Charles Kingsley, who, among other things, suggested that word on the street was that Newman actually suffered from “buyer’s remorse” about becoming a Catholic. To dispel all doubt, he put it as clearly as possible:

From the time that I became a Catholic, of course I have no further history of my religious opinions to narrate. In saying this, I do not mean to say that my mind has been idle, or that I have given up thinking on theological subjects; but that I have had no variations to record, and have had no anxiety of heart whatever. I have been in perfect peace and contentment; I never have had one doubt. I was not conscious to myself, on my conversion, of any change, intellectual or moral, wrought in my mind. I was not conscious of firmer faith in the fundamental truths of Revelation, or of more self-command; I had not more fervour; but it was like coming into port after a rough sea; and my happiness on that score remains to this day without interruption.

Newman’s relationship with the Catholic hierarchy could be compared to a bumpy road. That was especially so with regard to Pope Pius IX, who effectively responded to heresy charges against Newman by awarding him an honorary doctorate in sacred theology. Somewhat amusing but surely embarrassing for Newman, during his audience with the Pope, he banged his head on the pontifical knee as he executed the customary kissing of the papal slipper. It was also Pio Nono who deputed him to establish the Oratory in England and to establish what would become The Oratory School. Over time, however, Newman came to have very negative feelings for him and judged that the Pope had become a “tyrant”; he prayed—and encouraged others to pray—for an end to the pontificate (and we know what that meant in those days!).

At the age of 79, the venerable churchman was named a cardinal by Pope Leo XIII. Never one for fanfare or honors, nonetheless, the new Eminence exclaimed, “The cloud is lifted from me forever.” Vindication came late, but it did come. He took advantage of the requirement to offer a kind of acceptance speech to launch a frontal assault on what he called “liberalism in religion” which, he said, he had fought his entire life, both as an Anglican and as a Catholic. Always a bit of a hypochondriac, Newman had been dying for years; the conferral of the red hat, however, gave him a new lease on life, so that he even took on new projects. He adopted as his cardinalatial motto, Cor ad cor loquitur (Heart speaks to heart), summarizing his conviction that every person is called to a personal relationship with the Creator and, equally, that interpersonal relations are “the heart of the matter.” When asked by the members of his Oratory how he should now be addressed, he replied that, of all the titles he had ever borne, the only one that ever really mattered was that of “Father.”

Despite all the controversies into which Newman was drawn, he was ever the gentleman, perhaps reminding himself of his definition of a gentleman as “one who never inflicts pain.” He could disagree (and often did) without being disagreeable. While often attacked in ad hominem fashion, he remained civil.

Newman also had the uncanny gift of prescience. He had a way of peering into the future and seeing what others did not see or did not want to see. The finest example of that can be found in his sermon of October 2, 1873, for the opening of the first Catholic seminary in England after the Reformation, “The Infidelity of the Future.” In that peroration, he warned the future priests that the world in which they would serve as Christ’s ministers would be exponentially more challenging than what priests had faced in any previous era of Christian history. Reading that sermon today could make one assume that he had a crystal ball that let him hone in on the twenty-first century.

Having lived nearly ninety years of the century, Newman returned to his Maker on August 11, 1890. Seeming to forget the religious intolerance of the age, thousands upon thousands of Englishmen lined the streets as his funeral cortege brought his mortal remains to rest at Rednal.

Newman’s legacy

In our time, people often express concern for one’s “legacy.” What is Cardinal Newman’s legacy? It is found in the thousands of pages of his letters, diaries, sermons, meditations, poems, hymns, and dogmatic treatises, all coming from the pen of a man who was a pastor, educator, apologist, historian, philosopher, theologian, litterateur, and all-around man of culture. His mastery of the English language still has him ranked among the most revered in the literary canon of his land; the former prefect of the Congregation for Catholic Education in Rome, Cardinal Zenon Grocholewski, once told me he wanted to learn English well, precisely so as to read Newman in his native tongue. Newman’s theological contributions were as vast as were his interests: the meaning of conscience; development of doctrine; Mariology; the disastrous nature of liberalism in religion; the importance of a serious grounding in the Sacred Scriptures and the Fathers of the Church; the role of the laity within a hierarchical Church; the irreplaceable value of Church history; how to effect true ecclesial reform; the centrality of liturgical worship.

As I come to the end of this very frustrating but fulfilling effort to introduce our readers to this great man of the Church—frustrating, because so much more could and should be said; fulfilling, because it has enabled me to recall how much of my own priestly life and ministry have been lived under his wise and holy tutelage. The Venerable Pope Pius XII once uttered the hope that one day Newman would not only be admitted to the honors of the altar but would be likewise entered into that very select roster of doctors of the Church—a hope now being realized.

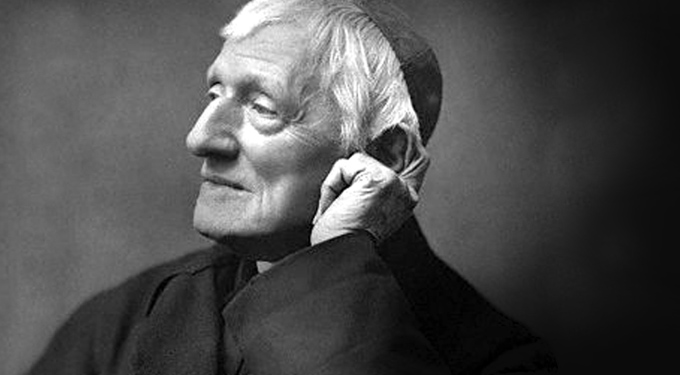

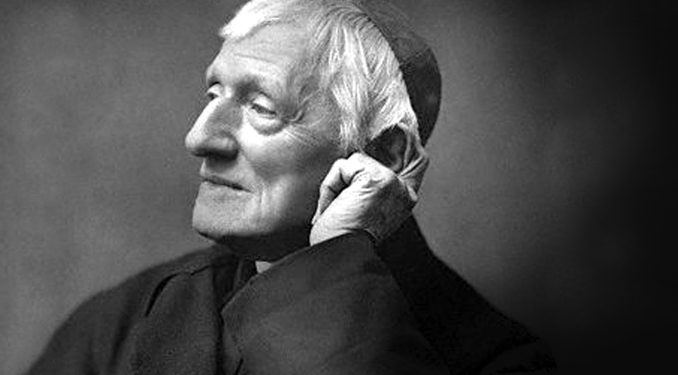

Newman was a very photographed person; oddly, for someone who was a source of joy to so many, it is hard to find an image of him with more than a hint of a smile. In Orthodoxy, Chesterton reflects on this matter in regard to Our Lord: “There was some one thing that was too great for God to show us when He walked upon our earth; and I have sometimes fancied that it was His mirth.” That may be said as well of Newman. The epitaph on his tombstone may give us a clue as to how this has all been resolved: “Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem” (From shadows and images into the truth). I hope that if I am able to join that “great cloud of witnesses” (Heb 12:1) someday, the great Cardinal will greet me with an equally great smile of welcome.

It is perhaps a sign of the workings of Providence that Leo XIII would have named Newman a cardinal, while Leo XIV is naming him a doctor of the Church!

St. John Henry, pray for us; pray especially for our one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church, which you so loved and for which you so generously labored.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.