The least revolutionary plans that New York City mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani advanced on the campaign trail dealt with mental illness. The most likely outcome of these plans is that taxpayers pay more for slightly worse outcomes and slightly worse mental-health services—with more untreated serious mental illness on the subways and streets as a result.

Mamdani’s mental-health policy seems to have been inspired by former mayor Bill de Blasio, of whom the mayor-elect is a fan. Under de Blasio, the city burned more than $1 billion on ThriveNYC, a mental-health bureaucracy that offered an array of wellness programs but did little for the seriously mentally ill. While Mayor Eric Adams laudably prioritized untreated serious mental illness during his one term, he did not abandon ThriveNYC programming, which Mamdani is rebranding as part of his “Department of Community Safety.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The lack of novelty is apparent in Mamdani’s most talked about mental-health proposal: deploying social workers instead of cops in response to emotionally disturbed person calls. New York City has experimented with non-cop and “co-response” teams since 2021, with mixed results.

There’s little new, either, in the rest of Mamdani’s mental-health platform, which offers standard progressive talking points, like expanded voluntary mental health and wellness services. Most New Yorkers agree that the city needs to address untreated serious mental illness. But more of the same won’t help allay these concerns.

Even if it did offer fresh solutions, Mamdani’s mental-health agenda, like many of his other campaign promises, is mostly beyond his power to implement. While the city has some control over the fate of the seriously mentally ill, the state plays a decisive role in the city’s mental-health care.

The state is largely responsible for the most critical aspect of New Yorkers’ mental-health system: psychiatric hospital beds. Governor Andrew Cuomo slashed capacity about 10 percent—a massive decline, given that the state already had a bed shortage.

The city is not powerless to change Albany’s mind, of course. Eric Adams’s persistent attention and pressure, for example, contributed to Cuomo successor Kathy Hochul’s decision to make significant investments in the state’s inpatient capacity. If Mamdani doesn’t speak up about the importance of these beds, however, the state might be inclined to slow needed expansion of its psychiatric centers.

The state, not the city, is also responsible for involuntary treatment standards. While Mamdani has said that he isn’t “fully convinced” of the efficacy of civil commitment—a rare but necessary feature of every state’s mental-health system that allows certain individuals with serious mental illness to be treated involuntarily—his opinion on this issue is less consequential today than it would have been last year. New York State codified new standards on civil commitment in May and is unlikely to make any more changes in the near term.

On involuntary care, the worst-case scenario for New Yorkers is that Mamdani diverts resources away from programs such as assisted outpatient treatment. AOT is a critical feature of New York’s mental-health system. The program facilitates court-mandated treatment for a select subgroup of people with serious mental illness who also have a history of violence and treatment non-compliance. The court both tracks participants’ compliance with their medical- and social-services regimen and forces mental-health-care providers to offer care for hard-to-serve people whom they otherwise would not treat.

Mamdani also has the power to decide how and when the NYPD delivers mentally ill persons to needed treatment, such as by bringing homeless New Yorkers in the throes of psychosis to the hospital. But at least in some cases, Mamdani doesn’t want police officers involved.

Rather, the mayor-elect has signaled that he wants to invest in voluntary programming. During an October interview, Mamdani was asked where he would send deteriorating, seriously mentally ill New Yorkers. He said that while existing laws provide for involuntary commitment, such treatment is often counterproductive, before pointing to something that he said “actually works”: clubhouses.

Clubhouses provide social services to seriously mentally ill but stable people. They do not offer clinical health or mental health-care treatment, and they do not accept prospective residents who “pose[] a significant and current threat to the Clubhouse community.” These institutions are not a real solution.

The city has funded 13 new clubhouses since 2023. If these “actually worked” in treating serious mental illness, we wouldn’t expect more than half of people incarcerated on Rikers Island to have a mental illness and annual 911 calls for “emotionally disturbed persons” to be approaching 200,000.

These failures underscore the broader point: Mamdani’s mental-health agenda won’t work because it didn’t work. His supposedly innovative policies are just more of the same of what we saw under Bill de Blasio.

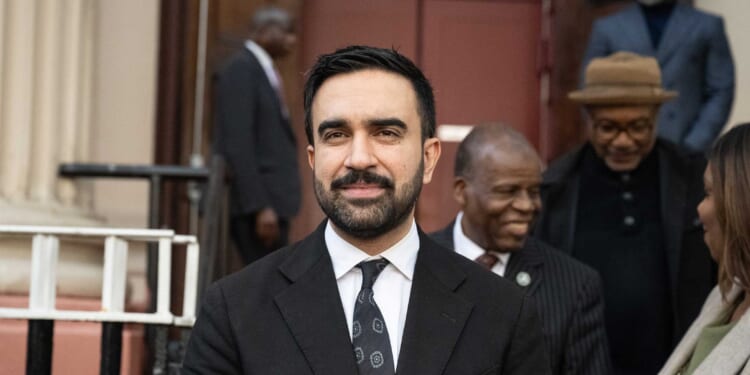

Photo by Stephanie Keith/Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link