In the spring of 1908, Claude Monet was in crisis. Since the universally acclaimed exhibition of his London pictures in 1904, the artist, cloistered in his Giverny house and garden with his second wife, Alice, had been obsessively working on a new, even more ambitious series: his Water Lilies. Yet, after years of work, Monet was so dissatisfied with the results that he was destroying one painting after another and even canceled the eagerly awaited exhibition in May 1908. His spirits were so low that he was on the verge of giving up on the Water Lilies altogether.

A change of scenery was clearly necessary. Alice convinced her husband to leave his water lilies and go with her to Venice in the autumn of the same year. Monet quickly succumbed to the city’s magic and over the course of ten weeks produced some thirty-seven paintings of La Serenissima’s most famous sites. Most of these works were shown together in Paris four years later, and then sold off and scattered across the Old and the New World. Now, for the first time since the 1912 show, more than half of Monet’s Venetian paintings are being displayed together in the Brooklyn Museum’s illuminating exhibition, “Monet and Venice,” curated by Lisa Small of the Brooklyn Museum and Melissa Buron, the former director of curatorial affairs at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

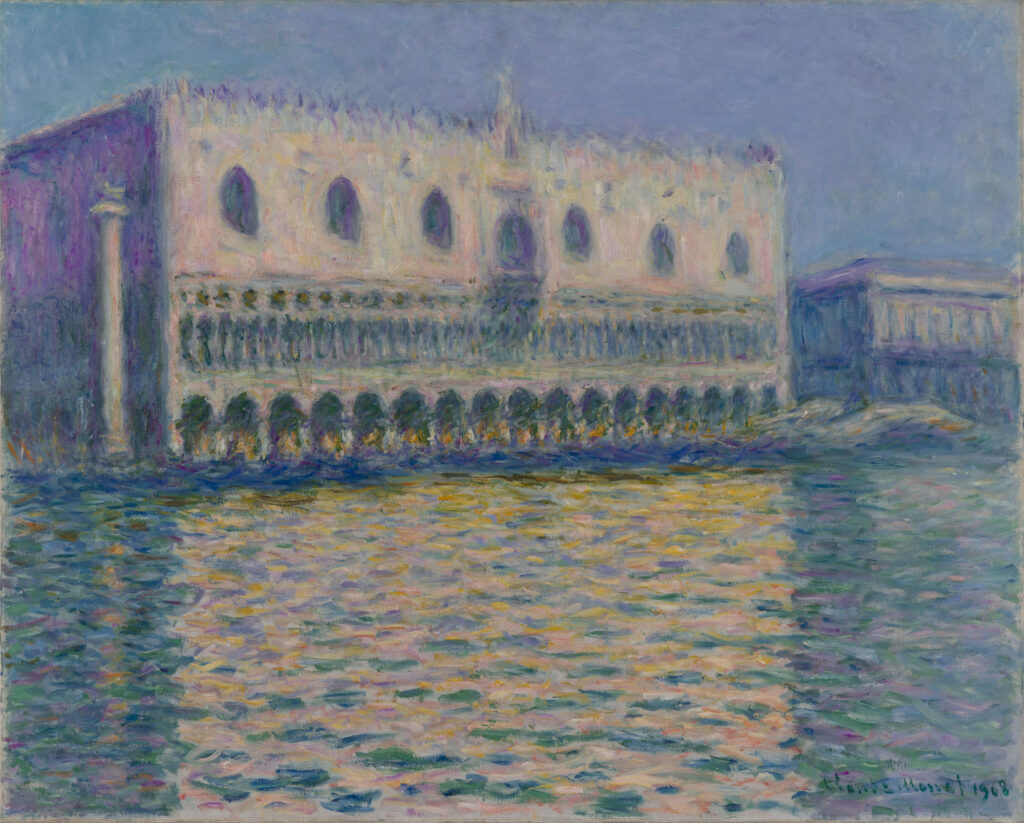

The first masterpiece one encounters is the Brooklyn Museum’s own Palazzo Ducale (1908). It is a close-up of the Gothic façade of the palace, painted by Monet in a gondola. The symmetry and verticality of the row of obscure arches, with yellow-orange splotches in the middle, at the base of the building contrast wonderfully with the quick, loose horizontal brushstrokes of dark blue and purple just below the arcade, dashes meant to suggest gondolas.

The work is completely devoid of human figures, an absence characteristic of all of Monet’s Venetian paintings. His Venice, frozen in time, is an island of lonely, splendid isolation. This sets him apart from his illustrious predecessors and contemporaries, whose paintings of Venice are teeming with life: at the beginning of the show, one is greeted with two paintings by Canaletto, one of which, The Bucintoro at the Molo on Ascension Day (ca. 1745), also shows the doge’s palace. Unlike in Monet where the palazzo takes pride of place, in Canaletto the structure serves only as a picturesque background to a quintessentially Venetian activity: the annual marriage celebration between the sea and Venice, as represented by her doge on his magnificent boat.

Renoir is another instructive foil suggested by the exhibition. His Palazzo Ducale (1881), painted from the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, shows the lagoon with gondolas and all manner of colorful boats, distracting the viewer from the monumentality of the architecture. The famous view of the doge’s palace and the Piazza San Marco from San Giorgio was a favorite motif of Monet, who painted the scene no fewer than five times, but his vision could not be more different. Unlike the busy canvases of Renoir and Canaletto, Monet, in his The Palazzo Ducale Seen from San Giorgio Maggiore, uses only three elements: shimmering water in the foreground, solid but barely discernible architectural forms in the background, and dreamy haze all around.

That last ingredient immerses the viewer into the Venetian atmosphere and helps distinguish Monet’s Venetian paintings from his contemporaries. Venice is uniquely suited for conveying that ephemeral, transformational light that Monet dubbed the enveloppe, and it gives every one of the works here a kind of nebulous fascination.

Monet had been pushing the envelope for decades. Just a couple of years before, he had achieved very similar effects in his London paintings, a couple of which are on view in a section of the exhibition contextualizing Monet’s Venetian group within the painter’s own artistic trajectory and life. We see how Monet’s fascination with water and reflection had developed over several decades, from the beaches of Normandy to the Seine.

Given his aquatic interest, it is all the more remarkable that Monet resisted the siren call of La Serenissima for so long, going only reluctantly at his wife’s insistence at the age of sixty-eight. Here too the exhibition explains the artist’s psychology: Venice, then as now, was quite simply too well known, too oversaturated with art history, “too beautiful to be painted” (in Monet’s words), thereby destining most attempts to paint the city to cliché. As Henry James wrote in 1909, “Venice has been painted and described many thousands of times, and of all the cities of the world is the easiest to visit without going there. . . . There is notoriously nothing more to be said on the subject.” In a world where every stone of Venice was famous, not least through the epochal work of John Ruskin, Monet did something remarkable in his paintings of the city: while drawing from the all-too-familiar repertoire of Venetian architectural views, he reinvigorated and reclaimed Venice’s monuments for nature, showing them not as quaint, tourist-infested relics of another age but as ephemeral and yet timeless visions. Monet here appears more as the last of the Romantics of the school of Turner than as a pioneering modernist.

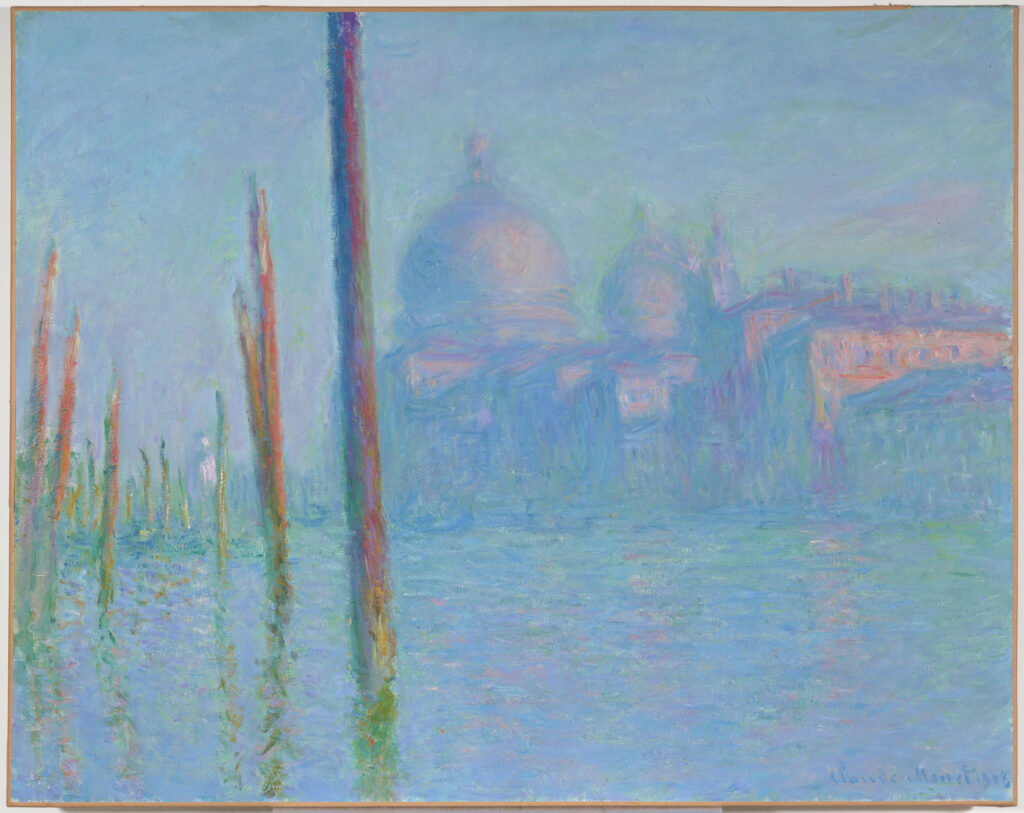

The exhibition culminates in a round gallery where one is surrounded by Monet’s Venetian paintings, grouped together by motif. We get to compare the enveloppes side by side, and the effect is nothing short of entrancing, particularly in the case of the two very fine paintings, both titled The Grand Canal, that show the evanescent domes of Santa Maria della Salute in the distance, contrasting with the jarring verticality of the Venetian pali, arranged diagonally so as to draw us into the luminous watery expanse. It’s also here that we learn of Alice Monet’s death (from leukemia), less than three years after the Venetian sojourn. This tragedy undoubtedly affected the final form of the Venetian paintings, which Monet was finishing in the months before and after her death. He wrote to his daughter, “I do not stop thinking about her while painting,” and it shows: these deserted, solemn paintings are suffused with melancholy, nowhere more evident than the bittersweet sunset depicted over San Giorgio Maggiore, on view in the last gallery.

Although tinged with sadness, the Venetian voyage proved to be decisive for Monet. He wrote to his dealer afterwards, “My trip to Venice has had the advantage of making me see my [waterlily] canvases with a better eye.” In the following years, he was able to successfully complete his Water Lilies series, several of which are on display in the exhibition. And indeed, as some critics already in Monet’s time noted, his misty Venetian palazzi themselves seem to float above the iridescent lagoon like proud water lilies in bloom.