James D. Watson, who died last week at 97, was the greatest biologist of his generation. He was also a cruelly treated target of cancel culture, shunned by the academic science community for which he had done so much and being held virtually incommunicado for the last 15 years of his life at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a leading biomedical research center that he had rescued from oblivion.

For as long as civilization endures, Watson will be remembered as the co-discoverer in 1953 of the structure of DNA, the hereditary material, an advance that laid the foundation for modern biology and medicine. But his talents were multidimensional. He was a great builder of institutions, reviving both the biology department at Harvard and then at Cold Spring Harbor. He was the architect of the Human Genome Project, though others seized credit for the implementation of his vision, and he made it one of the few large government projects to be completed on time and within budget—$3 billion over 15 years.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Watson also excelled as a writer. Over 1 million copies have been sold of The Double Helix, a racy narrative that forsook the usual pieties of scientific discovery and told instead of the passions and rivalry behind his and Crick’s pursuit of DNA. His textbook, The Molecular Biology of the Gene, defined for a generation of researchers how the new field should be approached.

If this abundance of talents weren’t enough, Watson was an eminently skilled political leader of the anarchic and sometimes myopic scientific community. When biologists first learned how to move genes from one organism to another, many wanted to assess the possibilities privately. Watson threw his weight behind a public discussion of the hazards—the Asilomar conference of 1975, which earned scientists enormous public trust.

Watson’s leadership was evident again in the launching of the Human Genome Project. Many biologists opposed the project, fearing that it would reduce the money available for personal research grants from their patron agency, the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Watson supported it, seeing it as a historic venture that would be undertaken by others if the NIH failed to take charge of it.

Watson passionately pursued the advancement of science, often deriding as fools or worse those whom he saw as standing in his way. But he was no mindless booster of science. He recognized that whatever scientists did should be acceptable to the public that supported their work. As first director of the Human Genome Project, he decided that 3 percent of its funds (later raised to 5 percent) would be devoted to assessing the ethical consequences of its findings. To thwart likely opposition, he announced the plan without telling his officials beforehand.

So how did a man of such accomplishments end up being ostracized by the very academic researchers whose careers he had made possible? Perhaps in emulation of his friend Francis Crick, though with less subtlety, Watson was given to making controversial statements as a way of challenging lazy thinking. Such remarks grew more hazardous in recent years as the woke-ification of the academic and media worlds got underway. Watson doubtless feared how this process would unfold—the relentless preferment of group identity over merit, with the steady degradation of the scientific enterprise to which he had devoted his life. If Harvard today epitomizes the ethos of the academic community, the old Harvard was led by distinguished scholars, such as the economist Larry Summers. The woke Harvard fired Summers for explaining (correctly) why there are fewer outstanding women scientists than men and chose instead to be represented by Claudine Gay, a black woman scholar with a meager publication record riddled with plagiary.

This is the context in which Watson unloaded a blunderbuss at the founding premise of woke ideology: that all groups have identical abilities and therefore must be promoted in proportion to their numbers. Perhaps over-obsessed with intelligence, as are many academics, he declared that blacks were less intelligent than whites. He issued brief versions of this remark on three occasions, and it was easy for journalists to string them together and make Watson sound like a raging racist.

Watson’s assertion was not without a basis, though few, if any, reporters possessed the courage to examine it. Decades of intelligence testing have established that population groups differ in their average IQ scores: the usual numbers are Ashkenazi Jews 115, East Asians 105, Europeans 100, African Americans 85. IQ scores come with many caveats and are highly contentious. The principal dispute among experts is not over particular scores, however, but on whether the differences arise from the environment or heredity, an issue that Watson did not get into at the time.

An open society would permit careful discussion of this divisive issue, though with considerably more context than Watson provided. Under wokeism, the media and academics sought the personal destruction of anyone who raised the issue. Watson apologized profusely for his remarks but to no avail. The woke monster is implacable; feeding it only stokes its appetite for further humiliation. Critics shook with outrage, much of it doubtless feigned, at Watson’s tactless remarks. For the remainder of his life, this most distinguished of Americans was rendered an outcast and nonperson, despite his towering contributions to scientific knowledge.

So fundamental is DNA to biology that the names of Watson and Crick are likely to be remembered alongside those of Darwin and Mendel, as the prime architects of modern biology.

“Every time you are in Watson’s presence you realize you are in contact with a man who has changed the course of human history and who will be remembered long after you have turned to dust,” Philip Sharp of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said in 1998.

James Watson was tall and gangly as a youth, and later in life, until past the age of 70, kept his figure trim by playing tennis. No one in his presence could imagine they were addressing an ordinary individual. Wayward wisps of gray hair suggested concerns that transcended quotidian grooming. He would stare at visitors with his ice-blue eyes, as if trying to see them from a great distance. Then, as he talked, his eyebrows would fly up, his whole face a statement of surprise as if he were himself dazzled by the clarity of the point he had just made.

His critics complained that he used the power of his celebrity as a license to say whatever he thought. But Watson’s put-downs usually had a purpose, being directed at anyone whose views seemed to him likely to thwart the progress of science. “It’s not promoting biology for its own sake—it’s because I am interested in the answers,” he said.

Watson let few things stand in the way of getting those answers. In his younger days, at the Harvard biological department in the 1950s and 1960s, he offered no quarter to those who could not understand that biology’s future lay at the molecular level, not in the traditional studies of the whole animal.

A faculty colleague at Harvard, Edward O. Wilson, the distinguished biologist and naturalist, was still seething over Watson’s behavior 30 years later when he wrote in his autobiography: “At department meetings Watson radiated contempt in all directions. He shunned ordinary courtesy and polite conversation, evidently in the belief that they would only encourage the traditionalists to stay around. His bad manners were tolerated because of the greatness of the discovery he had made, and because of its gathering aftermath . . . Watson, having arisen to historic fame at an early age, became the Caligula of biology.”

One need only recall the crazed Roman Emperor’s plan to make his horse a senator, or his murder of the child he conceived with his sister, to understand the bitterness of academic politics and the intense agitation Watson’s directness aroused in his colleague.

James Dewey Watson was born on Chicago’s South Side on April 6, 1928. His father, also named James Dewey Watson, was a debt collector who imparted to his son a love of bird-watching. His mother, the former Jean Mitchell, was an admissions officer at the University of Chicago and a precinct leader for the Democratic Party. A precocious student—he was one of the original Quiz Kids on the wartime radio program—he entered the University of Chicago at 15. He found physics and chemistry there not nearly so interesting as bird-watching but later, at Indiana University, where he got his Ph.D. degree, he began developing an interest in genetics.

Sent to Copenhagen for postdoctoral study with a Danish biochemist, Watson decided that the gene and its physical nature was the central problem in biology. At a seminar in Naples, Watson was electrified one day to hear in a lecture by Maurice H. F. Wilkins, a biophysicist of University College, London, that DNA could be crystallized. Though DNA had been implicated as the genetic material as early as 1944, biologists were slow to follow up this critical observation. The fact that DNA could be crystallized, however, meant to Watson that it must have a regular and perhaps ascertainable structure.

He determined to go where people were studying the structure of crystalline substances and in October 1951, without the permission of his funding agency in Washington, he transferred himself from Copenhagen to the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England. There, in the laboratory of the X-ray crystallographer Max Perutz, he met Francis Crick, an English scientist 12 year his senior but still working for his Ph.D. after a wartime diversion into designing sea mines. Like Watson, Crick had decided that the structure of DNA was the central problem of biology. Thereupon began a two-year intellectual partnership in which, without doing a single experiment, the two young scientists relied on their persistence, imagination, and data gleaned from others to intuit the structure of the genetic material.

Watson and Crick have each said that he could not have made the discovery without the other. Watson brought the knowledge of the American school of phage geneticists—biologists who study the simple viruses that prey on bacteria—while Crick was trained in the English school of X-ray crystallography pioneered by Sir Lawrence Bragg, the head of the Cavendish Laboratory.

But more than knowledge, it was the interaction of two powerful and special intelligences that brought the pursuit of DNA’s structure to fruition. “Jim and I hit it off immediately,” Crick later wrote, “partly because our interests were astonishingly similar and partly, I suspect, because a certain youthful arrogance, a ruthlessness, and an impatience with sloppy thinking came naturally to both of us.”

The two scientists believed from the start that the way to determine the structure of DNA was to build exact scale models, somewhat in the manner of a child’s Lego set. This was the approach successfully used by Linus Pauling, Bragg’s rival at the California Institute of Technology, in solving the structure of certain proteins. DNA was known to exist in the form of long chains, and Crick suspected from the X-ray pictures of DNA taken by Wilkins that the chains were likely to be wound in a spiral or helix.

The chains were made of alternating chemical groups known as ribose and phosphate, with each ribose carrying a small side attachment known to chemists as a base. Watson and Crick started by building the chains in the center of the molecule with the bases pointing outward because they could see no way in which two irregular sequences of bases would match neatly if centrally placed. The sequences had to be irregular if they embodied information.

When their model was finished, they proudly invited Wilkins and his new colleague Rosalind Franklin up from London to inspect the model. Franklin at once spotted a serious error. A few days later Bragg, embarrassed by the debacle of his associates trying and failing to solve Wilkins’s problem, ordered Watson and Crick to stop their work on DNA. They were in no position to object since Crick was supposed to be completing his Ph.D. thesis on protein structure and Watson, as a subterfuge to get his funding agency to acquiesce in his move to Cambridge, had said that he was working on plant viruses.

Despite Bragg’s prohibition, Watson and Crick continued thinking ceaselessly about DNA. A few months later, Watson saw an opportunity to reverse Bragg’s ruling when Pauling, Bragg’s peer and rival, announced a structure for DNA, albeit an incorrect one. This time Bragg did not resist Watson’s urging that he and Crick should resume their model building, lest Pauling realize his error and solve the great problem first.

In their second attempt, Watson and Crick took advantage of several new facts of which they were now aware. Through a reporting mechanism designed to share information among the laboratories of Britain’s Medical Research Council, Crick came to see more precise crystallographic data on DNA obtained by Wilkins’s colleague Franklin. (Franklin had already made this data public at a lecture that Watson attended. But Watson misunderstood a vital parameter, an error responsible for the erroneous model that he and Crick had displayed.) From the correct data Crick at once perceived a fact Franklin had not: that the two chains of DNA were anti-parallel, in other words, that the tail of one was laid against the head of the other.

The two biologists had also belatedly come across an important feature of DNA known as Chargaff’s rule. The four kinds of chemical base that occur in DNA are called adenine, guanine, thymine, and cytosine, or A, G, T and C for short. Erwin Chargaff, a chemist at Columbia University and a longtime student of DNA, had noted that from whatever organism DNA was extracted, A and T were found in about equal quantities, as were G and C.

Watson and Crick now began to wonder if the bases strung along the DNA helices might not point inward, a possibility that forced them to consider the bases’ structure more carefully than before. Through a stroke of great luck, they were sharing an office with Jerry Donohue, an American chemist who had worked for years with Pauling. Donohue told them of the right chemical structures for the bases, assuring them that the structures given in current textbooks had been arbitrarily assigned and were incorrect.

The moment of discovery was now at hand. Making cardboard cutouts of the correct structures—the Cavendish machine shop needed several more days to make metal ones—Watson tried to assemble them in like pairs, A with A, T with T and so forth, according to his current concept of DNA’s overall structure. But these attempts led nowhere. Shifting the cardboard pieces around on his small desk, he suddenly became aware that an A-T pair he had made was identical in shape to a G-C pair.

The observation at once suggested how bases jutting inward from the spiral stairways of the DNA chains could form steps of equal width, subject to these pairing rules. The pairing rule also explained Chargaff’s equivalences and, more importantly, how one DNA chain could serve as the template for building another, the essential prerequisite for any molecule that embodied hereditary information.

Crick was not more than halfway through the door, Watson wrote, “Before I let loose that the answer to everything was in our hands.” Crick was skeptical as a matter of principle but could maintain disbelief for only a few moments. He and Watson soon repaired to the Eagle, the pub at which they lunched every day, where Crick told everyone within hearing distance that they had discovered the secret of life.

And so they had.

“That morning,” wrote Horace Judson in The Eighth Day of Creation, his standard history of molecular biology, “Watson and Crick knew, although still in mind only, the entire structure: it had emerged from the shadow of billions of years, absolute and simple, and was seen and understood for the first time.”

The new model of DNA was built in a few days, and this time everyone was persuaded of its validity. Wilkins—to whom by the genteel rules of British science the DNA problem belonged—inspected their triumph with no hint of bitterness. A manuscript was sent off to Nature, the English scientific journal, where it was published on April 25, 1953.

Watson was just 25 and no doubt wondering what he could possibly do for an encore. He returned to the United States, spending two years at the California Institute of Technology, went back to Cambridge for a year, and in 1956 joined the biology department at Harvard. Crick was spearheading a worldwide drive by biologists to understand the genetic code, but Watson started developing another talent, that of a scientific administrator.

In 1962 Watson, Crick, and Wilkins won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Feminists assert that Franklin, too, would have deserved the prize had she lived; they allege that Watson and Crick stole her data and credit for the discovery. These accusations, based on distortions of a complex discovery history, are without merit. Franklin herself never claimed that she had been robbed of credit. She published all her DNA data, under her own name, in the same issue of Nature as Watson and Crick’s paper. She was two significant steps behind them, having seen neither that the two DNA chains were anti-parallel nor how the bases fit together in between—features that were the essence of the structure. Crick had wanted to acknowledge more explicitly their reliance on her data. Wilkins prevented him from doing this in his Nature paper, though Crick did so later.

Watson himself is much to blame for the myth of Franklin as the wronged heroine. In The Double Helix, he gleefully described how Wilkins had shown him a fine unpublished x-ray photo of DNA. The photo had been taken by Raymond Gosling, the technician whom Wilkins had been forced by his lab chief to hand over to Franklin. Gosling properly showed the photo to Wilkins, who remained his Ph.D. advisor. Wilkins was indiscreet in showing it to Watson but did so, he has written, because he was so infuriated that Franklin, having usurped the DNA problem from him, along with his technician and fine DNA sample, still refused to accept that its structure was helical, as the photo clearly showed.

The whole “Photograph 51” issue was irrelevant, however, despite Watson’s novelistic implication of purloined data, because Crick, the crystallographer of the team, had already obtained the data from the photo by other, fully legitimate means.

In 1948, as a young Ph.D. student, Watson had paid his first visit to the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a research institute based in the houses of a former whaling village on the north shore of Long Island. Thirty years later, he left Harvard and took over the institute, then much dilapidated. Through deft fund-raising among the old money families of Long Island, Watson transformed Cold Spring Harbor, making it a place of beauty, a leading center of biological research, and the foremost meeting place for the world’s molecular biologists.

Though he was a leading champion of biological research, Watson also insisted that the lab’s progress be subject to publicly acceptable ethical constraints, a position not always popular with his colleagues. After the invention of recombinant DNA, a method of transferring genes from one organism to another, Watson was one of the signatories of an influential letter to Science in 1974 that called for a moratorium on the new technique until its possible hazards were better understood.

The letter led the following year to a conference at Asilomar in California, at which, in a landmark example of self-restraint, biologists agreed to pursue the research but under stringent safeguards. (More recently, virologists exploring gain-of-function techniques were urged to follow the same procedure, a course that might have blocked the creation of the Covid-19 virus—but that proposal was rejected by the National Institutes of Health’s then leaders, Anthony Fauci and Francis Collins.) Shortly afterward, Watson again led the scientific community in criticizing the new safety rules, having decided the conjectured risks were overstated. Within a few years, the rules were substantially relaxed.

Another crisis in biological research brought Watson back into the public eye. By the mid-1980s, methods of determining the sequence of the bases in a DNA chain, and thus of reading the genetic information, had become so powerful that it seemed almost feasible to sequence the 3 billion base pairs of the human genome. Many biologists opposed the project, fearing its funding would reduce their own research budgets, and contended that it was poor science. Watson understood the project’s promise and pushed for the NIH to sponsor it. The agency chose him to lead the venture. “With Watson at the helm, it was difficult to argue that the science was mediocre,” wrote Robert Cook-Deegan in The Gene Wars, an account of the human genome project’s early years.

“I would only once have the opportunity,” Watson wrote, “to let my scientific career encompass a path from the double helix to the three billion steps of the human genome.”

Becoming first director of the human genome project at the NIH in October 1988, Watson shaped its goals and timetable. He decreed its official beginning to be October 1990 and set its completion date 15 years in the future, an adventurous but shrewd assessment of the technical possibilities.

He enlisted high quality scientists in the project. He insisted that the genomes of several simpler organisms, such as the C. elegans roundworm, be sequenced in parallel and as part of the human genome project, because these genomes would afford an essential basis for interpreting the human genome.

More than most biologists, Watson was conscious of the abuse of biological ideas that had led to the excesses of the eugenics movement, which ranged from the sterilization of the mentally defective in several countries to the sweeping atrocities of Nazi Germany. One of his predecessors at Cold Spring Harbor, Charles B. Davenport, had been a leader of the American eugenics movement in the 1930s. It was to reclaim and preserve the good name of biology that Watson repeatedly took the lead, while other biologists hung back or counseled silence, in calling for new biological techniques to be subjected to full ethical review.

Just as lottery winners often squander the fortunes thrust upon them, many people dissipate the windfall of sudden fame. James Watson, by contrast, earned fame at an early age and then, by force of character and clarity of vision, converted it into a means for him to influence the course of molecular biology. For many years he defined for his colleagues which broad fields of research were important and which ethical issues they had to address. The human genome project which he championed has become the foundation of twenty-first century biomedical research. From the structure of DNA to the sequence of the human genome marked a half century of extraordinary scientific progress. To a large extent, it was all shaped by one extraordinary individual.

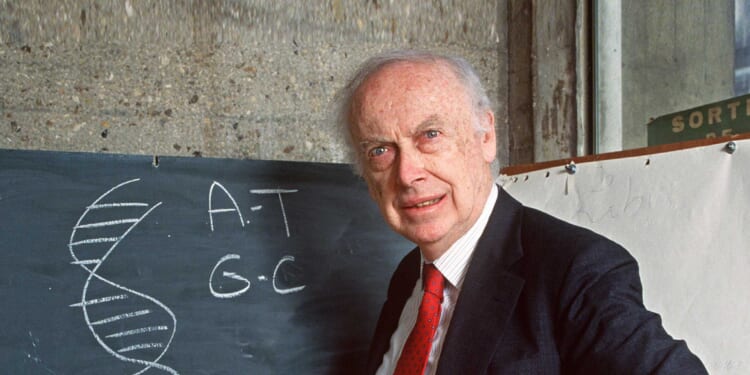

Top Photo: James Watson in 1993 (DANIEL MORDZINSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

Source link