Three days into the Israel–Iran Twelve-Day War in June of this year, an Iranian missile landed in Tel Aviv’s historic center, causing two buildings to collapse and sending shockwaves throughout a three-block radius. The Rubin Museum, a four-story house built in 1930, was one of several nearby buildings severely damaged. The Romanian-born painter Reuven Rubin (1893–1974) moved into this house in 1946 after immigrating to Mandatory Palestine two decades earlier. The home was gifted to the city upon Rubin’s death in 1974, and today, as the Rubin Museum, it houses the world’s largest collection of his art.

After the missile strike, the works in the Rubin Museum were evacuated across the city to the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (TAMA). “The following day—it was an emergency act—we absorbed their collection here,” TAMA’s chief curator Mira Lapidot told me. This afforded a rare opportunity to exhibit Rubin’s work from TAMA’s modern collection alongside select works normally kept in the artist’s former home. “Reuven Rubin: Be My Guest” unfolds the intertwined narratives of Rubin’s artistic development and the creation of a modern art tradition in Israel.

Rubin struggled as an aspiring artist in Chernivtsi (a Romanian city during his time, now part of Ukraine), New York City, and Bucharest after World War I. Arriving in Palestine in 1923, he immediately experienced a spiritual and artistic rebirth. “Here, in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, in Haifa and Tiberias, I feel myself reborn . . . . The grey clouds of Europe have disappeared . . . . I feel awakening in me all my latent energies,” Rubin recalled in his memoirs.

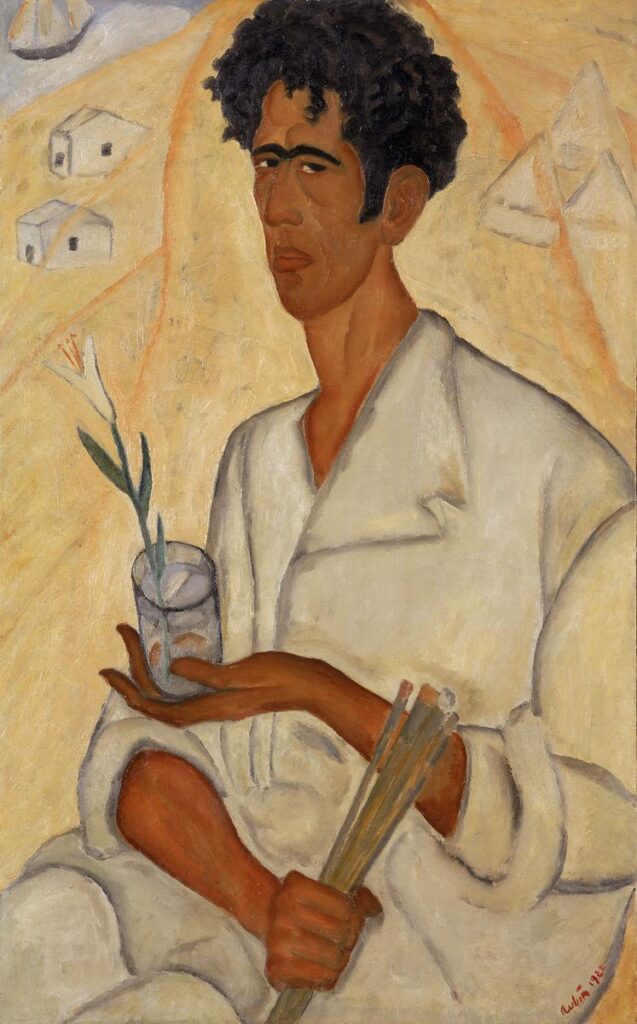

Reuven Rubin, Self-Portrait with Flower, 1922, Oil on canvas, Rubin Museum, Tel Aviv.

Two artworks bookend this early transitional period. The ghastly imagery in Temptation in the Desert (1921) is characteristic of the melancholic aura in Rubin’s immediate post-war work. The central figure in the painting appears lost and taunted by provocative figures around him. “It is I resisting temptation,” Rubin recalled, “continuing on my way of suffering in spite of the hands that reach out to grasp me.” Rubin identified with the tormented figure, and, as the title suggests, likened his torment to the sufferings of Jesus.

Two years later, Self-Portrait with Flower (1922) revealed a new artistic voice replete with symbolism, sun-kissed colors, and childlike imagery. The portrait depicts a bronzed Rubin, cloaked in white and framed against the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, and asserts his identity: the artist has a firm grip on his paintbrushes while cradling a budding flower symbolizing his rebirth amid the Jewish regeneration in the ancient homeland.

Rubin’s paintings over the following decades interpreted everyday life in Palestine through coded motifs of labor, rootedness, and progress, establishing a national iconography to give a pictorial embodiment of the Zionist ethos. In Jaffa Port (1923), two men set off to find work while glancing over their shoulders at a sleeping goat and a sprouting plant in the foreground, symbolizing the rest that follows a season of hard labor to build the national homeland. The Arab men smoking pipes in The Arabian Café (1923) carry an “air of leisurely abstraction and obvious content with the world,” noted one critic in 1924. For Rubin and other Jewish immigrants, the local Arab represented an inspiring rootedness and permanence in the land.

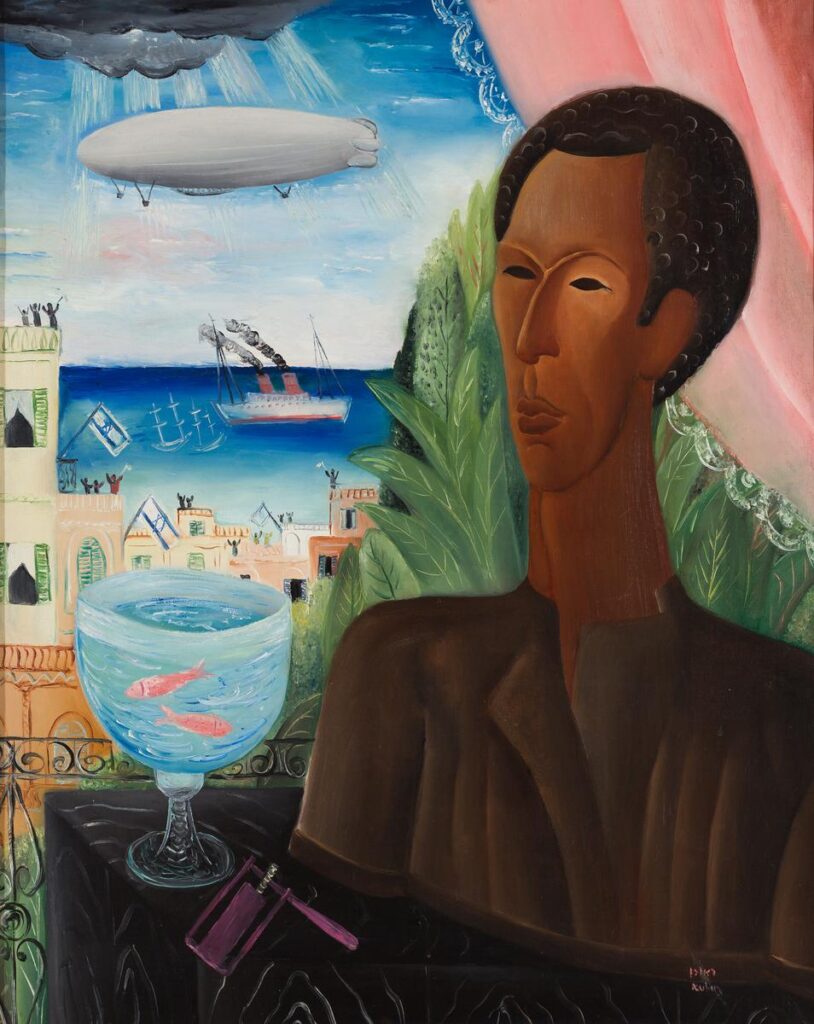

Rubin’s numerous scenes of a nascent Tel Aviv also highlighted Jewish progress and modernity. In Tel Aviv Seashore (1923–24), the Mediterranean tranquility embodied in the city’s first homes and sandy roads is interrupted by electric cables and a passing steamship. In Zeppelin over Tel Aviv (1929), the African-masked statue of Rubin that was carved by his contemporary Chana Orloff stands on a balcony terrace and looks out over a city full of three-story buildings as residents rush to welcome the arrival of an ocean liner and a zeppelin. As Jewish modernity was taking shape in Palestine, Rubin captured its essence through a naive simplicity reminiscent of the primitivism of Paul Gauguin.

Reuven Rubin, The Zeppelin over Tel Aviv, 1929, Oil on canvas, Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

Secular aspects of Zionism were balanced with religious tropes. Rubin distinguished the holiness of Tiberias, Safed, and especially Jerusalem by painting bird’s-eye vistas of their old city centers rather than street-level scenes. Rubin also boldly expressed Jewish sanctity through motifs borrowed from Christian art. In Dancers of Meron (1926), a cohort of pious Jews form a hermetic circle around their spiritual leader with the mystical cityscape of Safed in the distance. Their abnormally elongated bodies and stoic stares mimic Byzantine icons, and their rounded shtreimel hats recall the halos of medieval Christian saints. The motif is repeated in a grouping of women, sitting off to the side, as the central woman nurses a baby like the Madonna and Child.

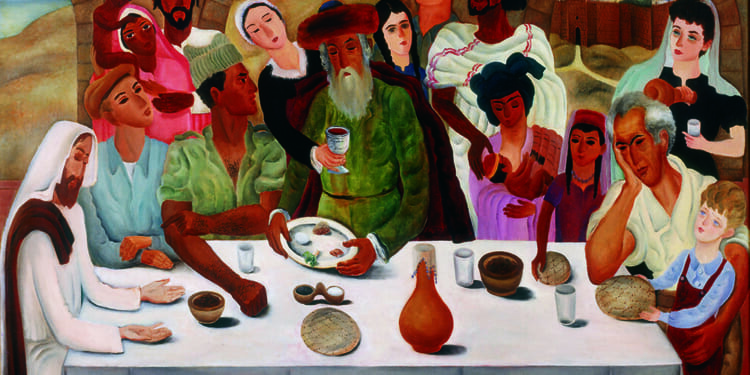

The First Seder in Jerusalem (1950) pays tribute to the establishment of the state of Israel with a theme inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (which was also the last Seder in Jerusalem for Jesus). Secular and religious immigrants, a Palmach soldier, and a rabbi—each given a didactic role in the rebirth of Jewish nationalism—gather for an imagined first Passover Seder in the new state. At one end of the table, however, sits a somewhat uninterested Rubin matched by a forlorn Jesus at the opposite end.

In light of the unexpected arrival of Rubin’s artwork, the TAMA curators noted how the exhibition embodies a relationship between host and guest, and how “hospitality requires sensitivity and profound responsibility toward the Other.” Perhaps no other exhibition is more suitable for this theme. Rubin held great reverence for the “others” around him—the Arab merchant, the Yemeni street sweeper, the Ashkenazi immigrant and pioneer, the mystical Kabbalists—and made it his vocational responsibility to capture them authentically. If nothing else, his work during the Mandate period and Israel’s early statehood can be understood as the projection of an idyllic future state where Jewish work and progress bear fertile fruit, Arabs smoke peacefully in the cafés, and Jesus is welcomed back to the Seder table.

For his first major solo exhibition in Jerusalem in 1924, after being in Palestine for barely one year, Rubin insisted that the exhibition flyers be printed in English, Hebrew, and Arabic, and recalled in his memoirs being “elated by the thought that I was pioneering good relations between the three peoples through the sacred power of art.”