On signing the Inflation Reduction Act on August 16, 2022, President Joe Biden called it “one of the most significant laws in our history.” With the new law, Biden said, “the American people won and the special interests lost.” He repeated the line.

The largest portion of the bill supposedly passed for the benefit of ordinary Americans went to tax credits for favored green corporations, amounting to more than half of the IRA’s nearly $400 billion in estimated environmental spending. The act also authorized hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidized financing for green corporations and environmentalist groups. Populist rhetoric aside, Biden was funneling unprecedented sums of money to a limited number of well-connected firms and “special interests.”

The government’s cost estimates for the act proved almost comically understated. Meantime, much of the new revenue that the law was supposed to generate never materialized. Many of the bill’s projects remain stuck in bureaucratic limbo.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Presented as a plan to reform the economy, tame inflation, and reduce the deficit, the Inflation Reduction Act will be remembered as ineffective in all but increasing both inflation and the deficit. From its name to its premise to its contents, the IRA was a patchwork of often contradictory ideas, hastily bundled together in one of the most brazen acts of political logrolling in recent memory. Biden’s presidency may be over, but Americans will be paying for this law—and its false promises—for years to come.

One of the IRA’s few saving graces is that it could have been much larger. Early in 2021, responding to the pandemic’s economic fallout, the White House proposed a Brobdingnagian plan known as Build Back Better. Divided into an infrastructure component and a catchall climate and social-services package, it aimed to fulfill nearly every progressive dream of recent decades. The legislative fight over the bill would become the defining battle of Biden’s presidency, as he himself acknowledged.

Despite progressive efforts to keep the two parts of Build Back Better together, what became the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed first. After further negotiations with Congress, Biden introduced the promised environmental and social-services package. Its scope was massive: the bill would create a universal pre-K program, fund child-care subsidies and four weeks of paid leave, raise the child tax credit, boost Obamacare subsidies, strengthen Medicare hearing benefits, expand government housing, enlarge Pell grants for college, increase funding for school meals, provide legal representation for illegal immigrants seeking asylum, and launch a version of the Green New Deal—complete with a new Civilian Climate Corps that would march into America’s forests and, by means not entirely clear, save the world from carbon dioxide. Advocates estimated the bill’s cost at $1.75 to $1.85 trillion. National Public Radio called this the “slimmed down” version of Biden’s earlier plan.

The House of Representatives approved the Build Back Better bill at the end of 2021, but in the Senate, it fell one vote short. Democrats launched an elaborate charm offensive to win over West Virginia senator Joe Manchin. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo invited him to her home for eggplant parmesan and his favorite scotch. National Economic Council director Brian Deese went zip-lining with Manchin at a West Virginia gorge. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer hosted a “Pasta Summit” for Manchin at an Italian restaurant on Capitol Hill.

The bonhomie worked. Manchin signed off on a reduced but still massive bill that included tax credits for producers and consumers of environmental goods, loans and grants for any group even remotely connected to renewable energy or fighting climate change, and about $100 billion in extraneous health-care subsidies. According to OpenSecrets.org, more than 2,000 organizations, from General Motors to the American Chemistry Council, lobbied on the measure. Due to heightened concerns about spending and inflation, the bill was incongruously titled the Inflation Reduction Act.

After the IRA passed, Manchin was less than pleased with the outcome. He had struck a deal with the White House and congressional Democrats to pass a permitting-reform act after the IRA, but both progressives and Republicans spiked it. Frustrated, Manchin accused the Biden administration of hijacking the bill through executive action to advance a “radical climate agenda.” “I will vote to repeal my own bill,” he later declared. But by then, it was too late.

The core of the IRA was providing corporations with tax credits for environmental activities, often awarded after extensive lobbying. Mike Carr, a former Department of Energy employee in the Obama administration, discussed how he helped craft an early version of the clean-energy manufacturing tax credit to benefit two solar-cell firms. After he persuaded some Democratic senators to introduce a bill that gave tax credits based on how many panels solar companies produced, the idea “started looking like the right approach for a bunch of other things,” and it “didn’t take long for the House to add wind technologies” to the list of businesses that could get the credit. Soon battery manufacturers came along, too, adding their industry and subsidies to the list. The earlier bill eventually got shoved into the IRA along with the new additions. Congress estimated that the law’s so-called 45X tax credit, designed to bolster the domestic manufacturing of clean-energy components, would cost $30 billion; but even at the time, Carr noted that it could “well exceed” that amount.

Despite the terminology, the IRA made clear that the “tax credits” were just cash. For one, the law let nonprofits, state and local governments, and other groups get a check for the credits even if they didn’t pay any taxes. It also allowed the “transferability” of credits, whereby companies could sell their credits for cash to others that needed them. Firms such as Basis Climate, Common Forge, Evergrow, Reunion Infrastructure, and Baker Tilly have launched their own marketplaces to help facilitate the trades between buyers and sellers of tax credits, which itself has become a lucrative financial activity.

Congress hoped to use these tax credits to encourage progressive changes in the economy. Companies building clean-energy manufacturing plants and generation projects, carbon-capture facilities, energy-efficient buildings, or EV charging stations had to meet new union prevailing-wage and apprenticeship standards to receive the full credits. The administration reduced penalties under the law if companies agreed to sign “project labor agreements” that allow “monitoring and administration by union officials.” Businesses could also get bonus credits for complying with other progressive wishes, such as building in low-income areas. One approving progressive news source stated that, before the IRA, everyone “had an incentive to keep costs as low as possible”; but now, “the top priority is getting that 30% tax credit” by splurging on union projects. And the “upside is valuable enough that it’s generated a whole new cottage industry in tax credit compliance” that would keep tabs on companies’ labor and union policies.

The act also doled out billions of dollars in tax credits for home energy efficiency improvements, which, studies have found, were more likely to be claimed by high-income households. According to journalist Franklin Foer, both Senator Manchin and President Biden “hated that rich families would receive tax credits to buy fancy electric cars.” But Biden either forgot or moved on from his earlier opposition, and his IRS soon loosened the rules for claiming the credits. He then imposed a mandate requiring automakers to make most new cars and trucks electric by the early 2030s—massively expanding the number of people who will be forced to buy EVs and, in turn, claim the accompanying credits. While original estimates put the bill for expanded EV tax credits at about $14 billion by 2031, newer projections suggested that they will cost almost $400 billion. Stanford researchers estimated that 75 percent of the subsidies will go to people who would have bought an EV anyway.

Congress soon realized that Biden’s mandates and regulations were making the bill far more expensive than expected. Less than a year after the IRA passed, new congressional estimates for the ten-year cost of the corporate electricity and energy tax credits had risen by 40 percent. Predicted costs for the tax credits for carbon-capture and clean-fuel technology had doubled. And the bill for the advanced manufacturing tax credits, as Carr had predicted, would “well exceed” initial projections: the expected costs were four times the original estimate. Congress would raise the expected price tag of the corporate tax credits again and again. Independent sources had even starker reevaluations. University of Pennsylvania researchers estimated that the act’s green spending portion would cost more than $1 trillion over ten years. Goldman Sachs suggested $1.2 trillion.

Besides tax credits, the other major component of a bill supposedly passed to help hardworking Americans was a vast expansion of subsidized loans for green projects—not exactly an item on any populist’s wish list. One of the strangest of these giveaways was the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, which allocated $20 billion in untethered grant money to nonprofits that would then loan out the funds.

Generous government grants to nonprofits are nothing new, but thanks to the IRA, the four largest federal grants to nonprofits on record were doled out by President Biden, not long before last November’s election. In contrast to many government lending programs, no pretense was made that the government would be repaid. These nonprofits would give the money to other nonprofits, which would then lend it to whatever environmental group—broadly defined—they chose. The recipients were at least two layers removed from direct government oversight.

The largest nonprofit beneficiary of federal largesse in modern history is the Climate United Fund, formed by activist lending groups specifically to receive the grant. As with other recipients of the greenhouse grants, the organization is populated by former Obama and Biden administration officials. On its own, the nearly $7 billion grant would make the Climate United Fund one of the 200 biggest banks in the nation, as measured by assets. For these billions, it submitted a 49-page work plan of generalized prose—not a bad per-page return. Instead of focusing on how to get the best returns for the money, the work plan notes that the fund will “center equity in access in our community engagement” and try to encourage more meetings about its projects, including by paying people to attend them. The group Inclusiv received $1.87 billion to support initiatives such as “Inclusiv Black Communities” and to “deliver products that address the effects of discrimination and bias in traditional financial services.” Its work plan wasn’t too bashful to note that, in distributing the money, it would require $187 million in overhead and funding for its own programs.

The IRA also created massive new lending programs to be run directly by the federal government. The bill authorized the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office to lend or guarantee up to $350 billion. By the generous standards of federal accounting, the government estimated that this vast outflow of subsidized loans would cost taxpayers only a few billion dollars.

Yet, studies have shown that the government consistently underestimates the cost of its lending programs. One reason is that these loans are often used to pursue political goals rather than maximize returns. The DOE, for instance, required IRA loan applicants to create “Community Benefits Plans” that detail which interest groups they will serve, their “community and labor engagement,” and how each project will “advance diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility.”

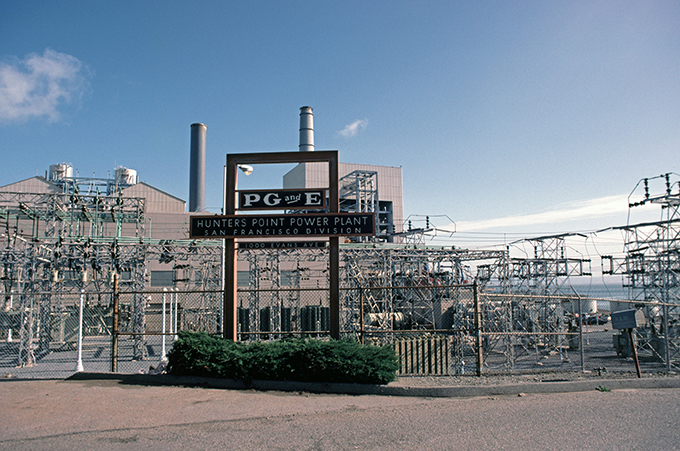

The San Francisco Bay Area utility PG&E got a $15 billion DOE loan after it submitted a community-benefits plan that committed it to “strong diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging principles.” PG&E promised to promote something called “spatial, procedural, and recognition justice,” which apparently means holding as many meetings as possible. PG&E pledged to back its three largest unions and enter contracts with more women-owned and minority-owned businesses. Since PG&E has gone bankrupt twice in the past quarter-century, partly under the burden of similar progressive mandates from California, the loan poses a not-insignificant risk for taxpayers.

Another reason federal loan programs often cost more than projected is that the government tends to bail out politically powerful borrowers. The American public has seen this pattern repeatedly, from federal housing loans to federal student loans. The IRA itself reflected this tendency by including an unrelated $3.1 billion in relief for farmers who had borrowed from the Department of Agriculture. In another era, a multibillion-dollar bailout of a government lending program would have made national headlines. In the IRA, it was buried in the fine print. Future presidents and Congresses will doubtless find ways to rescue firms that borrowed too much federal money under the act.

The premise of the IRA’s green financing drive is absurd, since no plausible argument can be made that green projects are underfinanced. On one recent estimate, $8 trillion in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) assets are under management in the United States alone. The largest banks in America pursue ESG directives that lead them to provide more loans to green groups. Public or quasi-public “green banks” already make environmental loans in 14 states. Extensive green lending programs operate at the DOE, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Department of Agriculture, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and other government entities.

Environmental projects are probably the most overfinanced initiatives in history. Having all this new federal money chase after a shrinking pool of viable projects will further reduce the returns on that lending and raise the chance of defaults—which taxpayers will have to cover.

The IRA not only hoped to use its credits and loans to create a corporate America more in line with Congress’s progressive image; it also wanted to remake America’s political system. The act gave $3 billion for “environmental and climate justice block grants.” These awards swiftly turned many small, so-called environmental-justice groups, which tie climate-change activism to race and class activism, into political behemoths. “We’re going from tens of thousands of dollars to developing and designing a program that will distribute billions,” observed Environmental Protection Agency head Michael Regan. The law’s language enabled grants to go to vague programs like “[c]limate resiliency and adaptation” and to facilitate “engagement of disadvantage communities” in “public processes.” In other words: activism.

To ensure that the grant funds were even less accountable to taxpayers, the government, as with the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, picked big nonprofits to hand out the money to smaller nonprofits as they saw fit. The administration gave $600 million to 11 so-called Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Grantmakers. The Institute for Sustainable Communities received $50 million to give out, thanks to its “equity-centered expertise.” The Climate Justice Alliance also was awarded $50 million, though it had previously portrayed itself as part of a movement that “challenges capitalism and both white supremacy and hetero-patriarchy.” Members of the Climate Justice Alliance have organized illegal protests at the U.S. Capitol and elsewhere about the Gaza war and backed a legal defense fund for those sabotaging “Cop City,” Atlanta’s police training center.

The IRA supported a $2 billion program of Community Change Grants. It has already provided $2.2 million to use “data, storytelling, and organizing training” for Youth Environmental Councils and Climate Action Groups in Ohio. It gives $3 million to allow “tribal elders, traditional ricers, and knowledge Keepers” to participate in a project “to protect wild rice” in Michigan, as well as $1.5 million to teach prisoners and former prisoners “about the unique environmental and climate justice challenges” that they face.

The Biden administration’s so-called Justice40 initiative tried to apply the environmental-justice framework embodied in the IRA to all aspects of government. Justice40 demanded that at least 40 percent of the benefits of all federal green energy spending flow to “environmental-justice communities,” defined as low-income areas with a pressing environmental issue. As Manhattan Institute fellow James B. Meigs notes, the initiative involved opening a host of new programs and offices. The White House launched an Environmental Justice Scorecard to keep agencies updated on their progress toward the 40 percent goal, a White House Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights to enforce its dictates, and a Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool for those winning grants to show that they were acting in an environmentally just manner.

The IRA also effectively bribed state and local governments to implement a key part of the Green New Deal. The act provided $1 billion to governments willing to adopt the 2021 International Energy Conservation Code for buildings or, more expansively, codes that promise “zero energy” use in new buildings. Far from driving down inflation, the codes will significantly drive up the cost of new housing. A National Association of Homebuilders report estimated that the 2021 IECC would increase new housing costs by over $30,000 and will take up to 90 years for homebuyers to recover through energy savings. Even supporters admit that the codes add thousands of dollars to housing costs—and “zero energy” buildings will cost even more.

The IRA contained so many disparate programs—119 in all, on one estimate—that even many attentive commentators are unaware of them. The IRA offered an impressive $100 million to start a program for sticking labels on “low-emissions construction materials.” After holding several webinars trying to figure out what this meant, the EPA remained uncertain. By the Biden administration’s end, the funds still had not been distributed.

The law allocated $3 billion to revamp and electrify the basic postal delivery truck. The Postal Service projected that 3,000 of the so-called Next Generation Delivery Vehicles would be ready by the November election. By that time, in a familiar pattern, the government had received only 93 trucks. According to the Washington Post, the electric versions of these vehicles cost $77,692 each—about 40 percent more than the gas-powered versions—and offered a shorter range. For purchasing fewer than 100 overpriced electric trucks, the Biden administration awarded the Postal Service its “federal sustainability award.”

Though the IRA was billed as a climate bill, it also directed more than $100 billion to health-care subsidies, with the largest share funding the Obamacare insurance market. The administration claimed that this would reduce insurance costs for struggling families. Yet the law removed the cap on subsidies for higher earners—meaning that, thanks to the IRA, people making hundreds of thousands of dollars a year can now have their health care subsidized by the federal government. An Urban Institute estimate found that the largest beneficiaries—by far—on the Obamacare exchanges would be those making more than 400 percent of the poverty level.

Despite the IRA’s immense price tag, the Biden administration claimed that the act would reduce the deficit through new taxes, revenues, and spending cuts. The largest share of these revenues was supposed to come from a corporate minimum tax, aimed at preventing large corporations from using deductions and loopholes to lower their tax rate below 15 percent of income. Given that the IRA’s main purpose was to provide tax benefits for corporations, this new minimum tax was deeply ironic. To shield the IRA’s centerpiece—its clean energy tax credits—from the very tax meant to fund the law, the administration announced that most of those credits would be exempt from the minimum tax.

In a typical example of Washington accounting, another major source of revenue in the IRA was supposed to come from increased government spending. The bill allocated $80 billion to expand the IRS workforce, with Congress estimating that the new agents would generate more than twice that amount through heightened enforcement. The administration, never shy about exaggeration, claimed that the effort could raise more than ten times its cost. But by late 2024, the administration admitted that it had recouped just over $1 billion from its increased enforcement efforts. By every measure—including the government’s own—the bill will now add hundreds of billions of dollars to the deficit.

The IRA’s climate benefits turned out to be largely specious, as well. Some sources stated that the act would cut carbon emissions by up to 40 percent by 2030. Senate Democrats and the EPA itself repeated this claim, based on misreadings of studies that the bill would assist in cutting overall U.S. emissions to 40 percent below 2005 levels—thus only accelerating a reduction in emissions already under way. Even these assumptions were overestimated. As Scientific American pointed out, almost any substantial reductions in the next few years would be difficult, if not impossible, since it can take more than a decade to complete a single electric transmission line to a new renewable project. The idea that hundreds of these would be connected and obliterate large sections of the fossil-fuel industry in a few years was literally incredible.

The new Trump administration is no fan of the IRA. One of President Trump’s first executive orders involved “Terminating the Green New Deal.” It paused the distribution of funds from the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. New Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has called the IRA a “doomsday machine for the budget,” and both Trump and Bessent have promised to pare back its tax credits for electric vehicles and other green programs. The administration has placed on administrative leave about 200 employees in Biden’s environmental-justice offices, from the EPA to the Department of Justice. The new Congress is looking to claw back some of the IRA as well.

Yet stopping the IRA’s money gusher won’t be easy. Just before Biden left office, the White House announced that it had dispersed 84 percent of the law’s clean energy grants. The rapid push of funds out the door, officials suggested, would protect the grants from the incoming Trump administration. The outgoing administration also announced some $11 billion in extra grant funds, without finishing the legal process of dispersing them. Kristina Costa, a Biden White House assistant, noted that the announcement “creates some political pressure” to spend the funds later. One video caught a Biden EPA official describing the effort to get IRA money out the door as like “tossing gold bars off the Titanic.”

The Biden administration tried to get the biggest green loans out just before he exited. The largest IRA lending program announced its first loans right after the election, in December 2024. Four days before leaving office, Biden committed another $22 billion in loans to utilities. The DOE lamented that it had billions more to give.

After the passage of the IRA, a New York Times headline wondered, “Did Democrats Just Save Civilization?” On the contrary, the law gave mountains of money to questionable companies, nonprofits, and well-off consumers, at an astounding cost to taxpayers. The spending, loan losses, and politicized projects will weigh on the U.S. economy for years, while the supposed benefits evaporate into the atmosphere.

Top Photo: When he signed the IRA on August 16, 2022, President Biden called it “one of the most significant laws in our history.” (Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images)

Source link