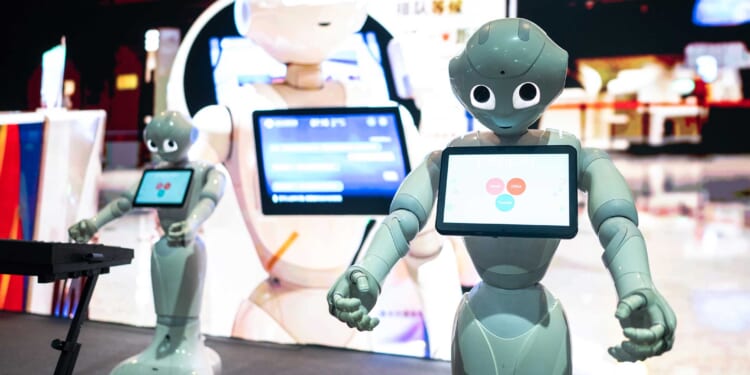

The stock price of Nvidia, an artificial intelligence company that makes a product most people can’t explain, has entered the realm of kitchen-table conversations—as has AI itself. The exuberance and the anxieties around AI are being driven not only by eye-watering levels of spending and stock valuations but also by the question of whether the technology is truly consequential.

The AI revolution is no different than earlier technological revolutions: the trajectory of its market adoption will become clear only in hindsight. Meantime, to find predictive patterns, economists, policymakers, stock pickers, and historians fall back on analogies instead of mere numbers.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

We’ve already seen AI analogized with, for example, the 1999 Internet bubble, the space race, the railroad era, and the first radios in the 1920s, wherein RCA’s soaring stock bubble burst along with the 1929 market crash. But those analogies are not relevant to AI because, while they recognize the technology’s novelty or market hype, they fail to capture the reach and depth of applicability and the scale of associated infrastructures. Not even close.

Consider: the invention of the automobile was revolutionary, but the advent of a useful electric car was a mere novelty. The arrival of jet engines was both novel and consequential in accelerating what was by then a three-decade-old commercial aviation revolution. But while aluminum-bodied jets fueled the growth of a trillion-dollar global tourist industry, they didn’t change, for example, how we fabricate aluminum or any other critical process.

The closest analogy for AI is one that has been entirely ignored thus far, one that captures the characteristics and scope of the AI revolution: i.e., the century-and-a-half-ago development of chemical science and the resultant massive expansion of an industry that did indeed “change everything.” But first, it’s instructive to explore further where the other technology analogies go wrong.

In the pantheon of such, credit goes to eminent historian Niall Ferguson for the most imaginative yet. In his recent big read for The Free Press, Ferguson suggests that AI stock promoters sound like the Dr. Seuss character pitching green eggs and ham. He also offered, more seriously, the popular analogy with the great railroad buildout of the nineteenth century, which was not only consequential but also the cause of more than one boom-bust cycle in the stock market.

Two things can be “true at the same time,” as Ferguson writes. A technology driving a boom can be revolutionary, while stock markets and the technology’s promoters simultaneously overvalue the associated companies.

Nevertheless, it matters to investors and policymakers—for different but related reasons—where we are in any boom-bust cycle. Are we at the beginning of the end, or the end of the beginning? That’s where the right analogy can be useful.

Most pundits have dropped the Internet/telecom bubble analogy, which constitutes a category error. While AI requires communications and can make those systems more effective, AI is not itself a communications system.

Others have likened AI with construction bubbles, recalling the 2007 housing market crash. Annual spending on U.S. data center construction has now surpassed annual spending on all office building construction. But, again, while buildings (giant data centers) are needed to house the AI hardware, AI itself isn’t about buildings.

Analogizing AI with the arrival of the railroad age is similarly misleading. As consequential as the railroads were in accelerating the transformation from an agrarian to industrial society, railroads constituted a revolution in transportation, as did the automobile and aircraft later. AI is not a transportation technology (though it will change that market—think drones and robotaxis). Nonetheless, if railroads were a good proxy, then in terms of private capital being deployed, the current torrent of money devoted to AI—measured as a share of the total U.S. economy—would need nearly to triple its current levels to match peak railroad spending.

Note that there was little anxiety about over-investment in the later transportation revolutions of the automotive and aviation industries. That suggests an important truth about stock market psychology. During those eras, transportation-centric companies followed the normal trajectory: some soared, some dominated, and others evaporated. History also does not record any handwringing over the astonishing energy demands that accompanied those transportation revolutions.

Still others analogize the AI boom with the huge buildout of the electricity industry a century ago. This, too, is a category error. Infrastructures that produce energy are different from those that use it. But if one wants to insist on the electricity analogy, spending on power and grid infrastructure as a share of GDP around 1920 was triple the level of today’s AI spending as a share of GDP.

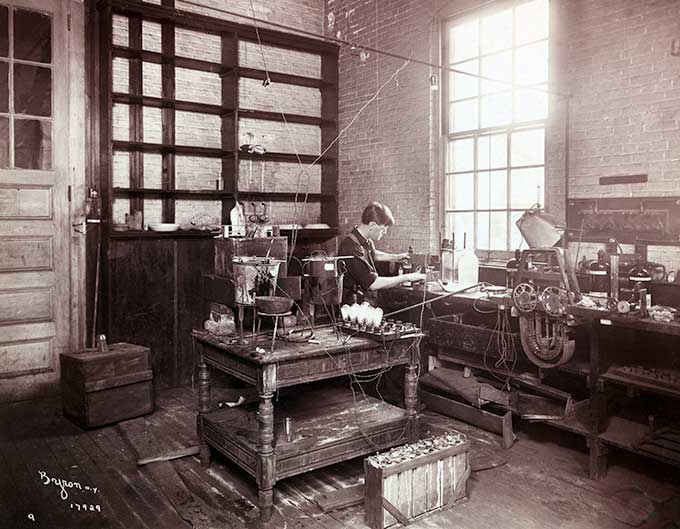

A more suitable analogy for artificial intelligence? The invention of artificial illumination. It’s easy to forget just how consequential electric lighting was.

As technology brought exponentially cheaper lighting, the democratization of artificial illumination proved enormously consequential. Factories and cities could function at night, boosting production and productivity. Street lighting improved public safety. Lighting technology infused and affected science itself and enabled new chemical processes. Lighting tech led directly to the invention of movies, and thus Hollywood. It’s a straight line from the Edison bulb to the miraculous laser that is now used for everything from communications and eye surgery to welding and weapons.

For those counting BTUs, artificial illumination a century ago consumed over half of all electricity. Creating evanescent photons still uses about one-fifth of all electricity on a global basis.

Which brings us back to what is arguably the best analogy for the AI revolution: the chemical revolution that began at the end of the nineteenth century. The science of combining basic elements in novel ways, via rules and formulae—the “code” of chemistry—led to countless new classes of products and services, from fertilizers and fuels to pharmaceuticals.

The arrival of chemical science changed the world and affected every sector of the economy. It led to massive investments in industrial infrastructures in the early twentieth century.

The emergence of the underlying science and mathematics of AI is similarly expansive and revolutionary, as acknowledged by the Nobel Committee with its 2024 Physics and Chemistry Prizes. AI enables the combining of basic data in novel ways to produce completely new classes of products and services. As the co-recipient of that prize, Geoffrey Hinton, said in his Nobel acceptance speech, AI “will increase productivity in almost all industries. If the benefits of the increased productivity can be shared equally it will be a wonderful advance for all humanity.”

In the early days of the chemical industry, the U.S. witnessed a furious pace of private-sector spending on construction. Census data from the turn of the twentieth century show that private capital deployed across chemical domains rose rapidly from 1 percent to more than 6 percent of the GDP—the latter, again, is triple the share of today’s spending on AI infrastructure.

The fact of an AI boom does not, of course, address the worries about the effects of AI on news, social media, art, jobs of all kinds, or national security. Different analogies are needed to address those issues.

On great power competition, for example, analogizing AI with the space race of the 1960s represents yet another category error. There was not then, nor is there now, any possibility of everyone going to the moon. But AI, like chemistry before it, will extend its effects into everything.

Speaking of things to worry about: it bears noting that spending on chemical industries ballooned, briefly, to 9 percent of GDP during World War I in one of history’s more odious examples of a technology being diverted to warfighting. (The postwar industrial investment rate relaxed back to the peacetime trend.) One can hope that history neither repeats nor rhymes this time around.

As for the trope that AI is job-destroying, consider the commonly repeated example of the ATM as a destroyer of bank teller jobs. Analysts at J. P. Morgan pointed to Bureau of Labor Statistics data showing that, as the number of ATMs rose some 800 percent over the past four decades, the number of bank tellers employed also increased—albeit by only 20 percent. The effects of AI will likely be similar.

Of course, some jobs will disappear. But as the brilliant MIT economist David Autor has documented, because of the combination of automation and technology changes, more than half of all job categories that existed in the 1940s don’t exist today. The result, however, has not been a 50 percent unemployment rate. Autor recently offered the argument that AI, if “used well . . . can assist with restoring the middle-skill, middle-class heart of the U.S. labor market that has been hollowed out by automation and globalization.”

AI is self-evidently revolutionary. Regardless of whether stock pickers are bullish or bearish about AI companies, analogizing is the best tool we have for guessing the shape of an AI-animated future. The odds are high that we are indeed at the end of a beginning, not the inverse.

Top Photo by John Ricky/Anadolu via Getty Images

Source link