Talk to enough people of family-starting age, and you’re likely to hear the complaint that the right house is too expensive—or doesn’t exist. A decent house would mean either a 90-minute commute or a move to a city with no jobs.

Along with childcare and education expenses, housing costs were one of the most prevalent factors named among Americans under 40 interested in starting families, according to an Institute for Family Studies survey conducted last year. Twenty-five percent of respondents cited housing costs, while just 8 percent reported lack of supportive family policy as an issue and 10 percent identified debt burdens.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

But you don’t need surveys to prove that housing matters. Kids take up space. Americans today have expectations of space and privacy that require extra bedrooms for family formation to occur. Moreover, families desire other housing- and neighborhood-related goods: safety from crime, good schools, attractive parks, and sidewalks or safe streets for children’s bicycles.

We explored these preferences in the IFS survey. Using a series of forced-choice-style questions that required survey respondents to select among various tradeoffs, we found that single-family houses with three or more bedrooms are, without any close competition, the preferred arrangement for American family formation. This result holds for every religious, geographic, political, and demographic subgroup we could analyze. And it’s not just true in the abstract—vacancy rates of starter homes, along with the implied budgetary constraints we imposed on our respondents selecting these homes, suggest that this desire is an almost-universal norm of American culture today.

On that basis, we suggested numerous policies to generate more of this kind of housing. With America’s birth rate at record lows, the least policymakers can do is try to remove needless barriers to the supply of family-friendly homes. We then did a second study, asking, “How can we make real estate development slightly less catastrophically bad for families?”

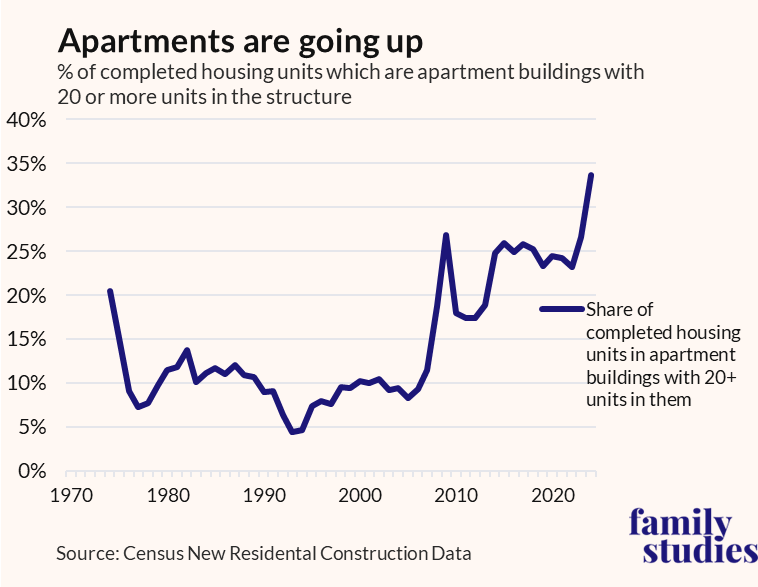

To understand where this report is coming from, you first need to understand how American housing is changing. The figure below shows the share of new housing accounted for by apartments.

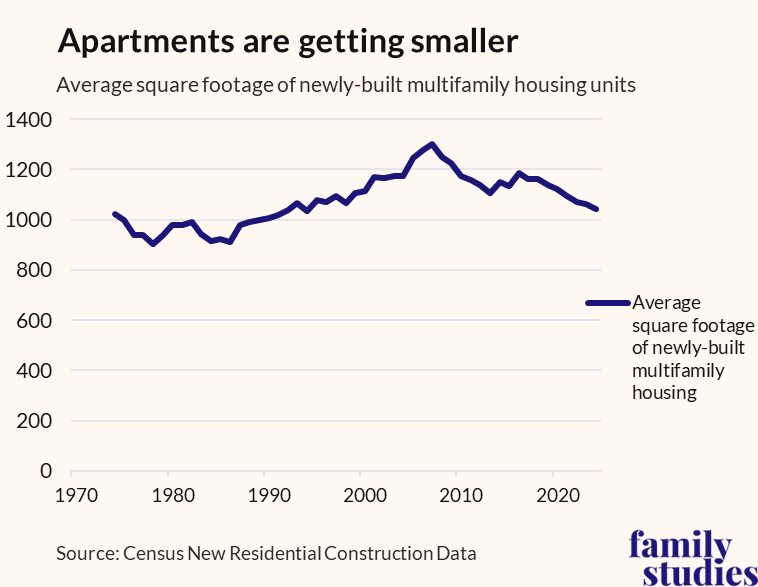

Apartment construction is running at a record high, even as we know that apartments are not where Americans want to raise their families. Even worse, the apartments are getting smaller.

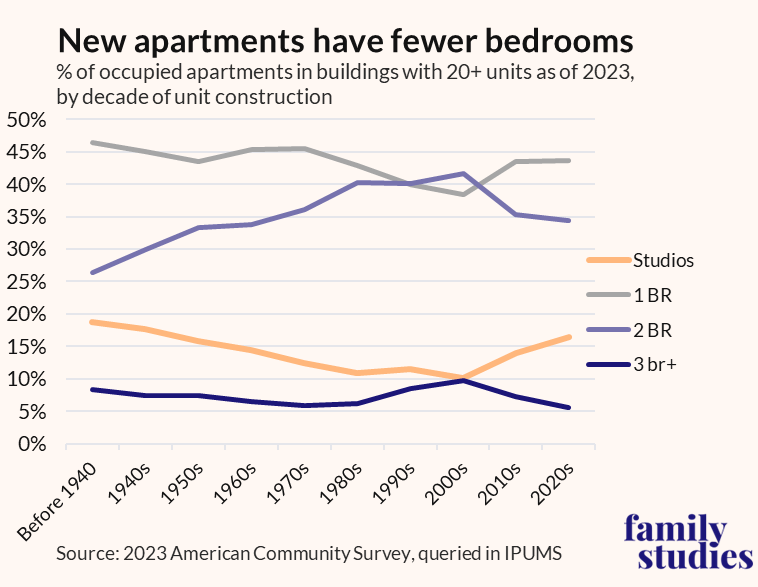

The steady decline in bedroom counts and square footage in apartments over the past 30 years means that the boom in apartments is adding even less family-friendly housing than you might think. The buildings going up don’t contain an even mix of unit sizes: more than half of the units are one bedroom or less, and barely 5 percent are the family-friendly, three-bedroom units that Americans want.

Many reasons explain this shift—some regulatory, some just a feature of the private market. Delayed family formation and a large Millennial generation coming of age in post-Great Recession credit crunch created a massive surge in demand for rental apartments. Developers surged production of this housing.

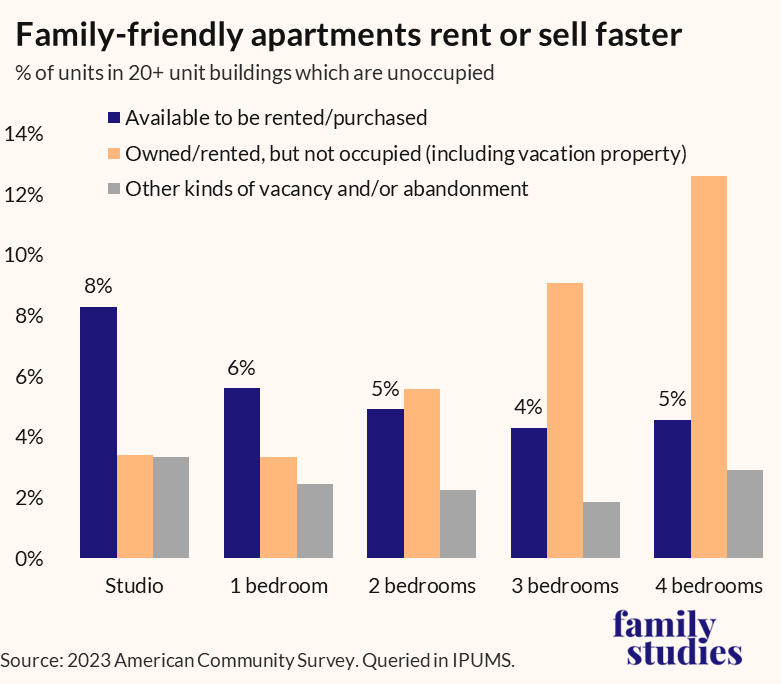

But many developers failed to realize, first, that this shift was not permanent, and second, that future cohorts would be smaller. Gen Z is smaller than the Millennial generation, and millennials are now marrying and having babies. As a result, vacancy rates for small apartments are rising and now stand at double the vacancy rates for bigger units, even as family-friendly apartments with three or more bedrooms increasingly get bought up as vacation properties and Airbnbs.

We wanted to understand these dynamics better. If we built more family-friendly apartments, would Americans actually be interested in them? Would they pay for them? And would they have more babies?

The answers we found were yes, yes, and yes. Strikingly, bedroom counts matter, but square footage doesn’t. We found that showing respondents scenarios with two bedrooms rather than one increased demand just as much as showing them a $2,000 difference in rent. (Obviously, two-bedroom units don’t go for $2,000 more—because people who can afford that amount move into townhouses or the suburbs, or because the people who prefer those bedrooms can’t afford them.) Square footage variations drove comparatively far smaller differences in preferred scenarios in our survey.

Market prices represent the intersection of willingness and ability to pay for a product. Our survey measures only willingness, and willingness is measured within the survey’s constraints—in this case, that all options presented were apartments.

Nonetheless, this tells us that there is meaningful pent-up demand for more bedrooms. Americans, especially those who have or want children, value bedrooms even more than square footage. The open floor plan is anathema to American family life.

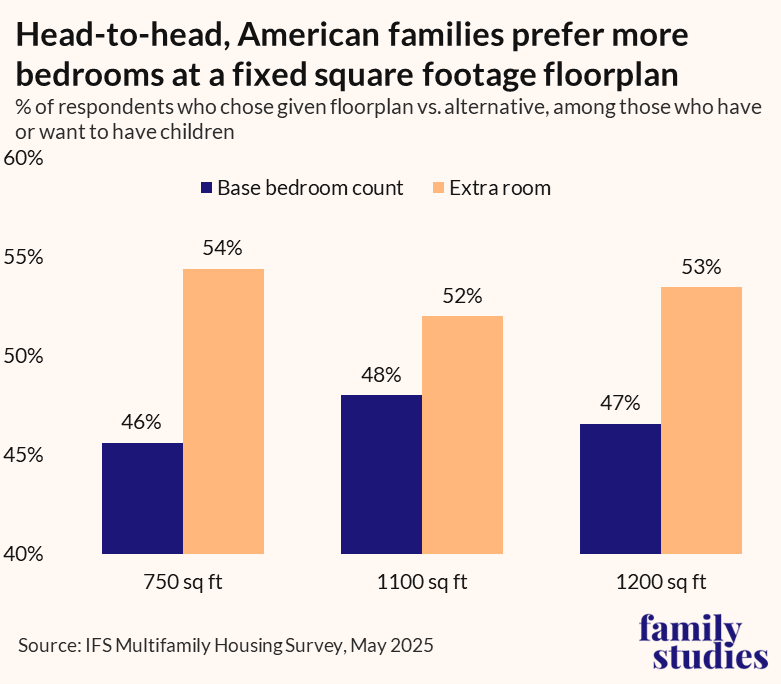

Next, my co-author Bobby Fijan and I produced realistic renderings of apartment floor plans. We showed respondents these floor plans in randomized head-to-head matchups and asked them to select one. While selections were relatively close (partly because the floor plans were similar, with many respondents reporting that they didn’t see a difference between them), the “Extra bedroom” layout was preferred at every apartment size we tested.

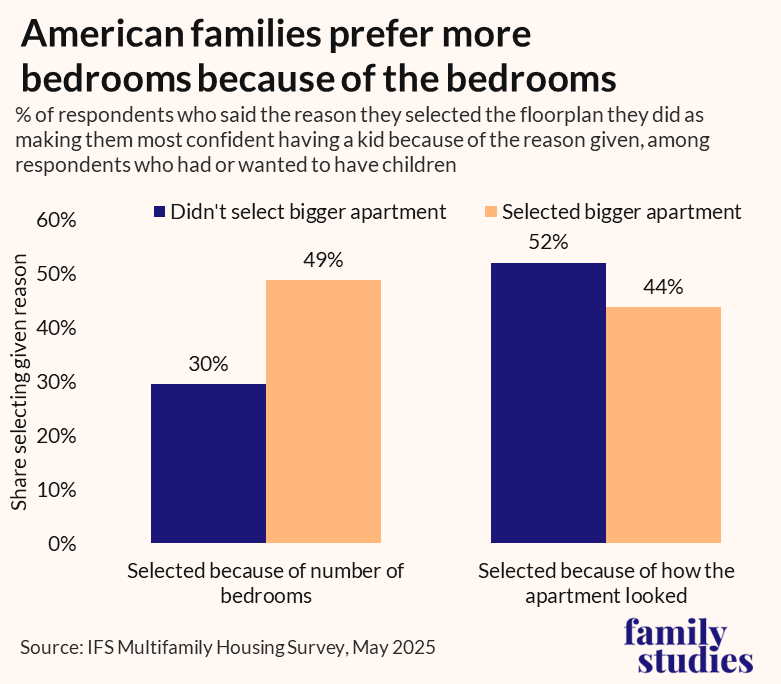

When we asked respondents why they made their choice, the answer was clear: people who chose the extra bedroom unit really did choose it because of the number of bedrooms.

We used several other questions to test preferences. We had respondents score the importance of various amenities (bedroom counts clobbered every other amenity). We had them rank floor plans in order of preference (more bedrooms led to better rankings). We asked them about housings costs and ideal housing types.

We found, across every method we checked, compelling evidence that Americans prefer apartments with more bedrooms. For the 750-square-foot floor plans, we even found that childless-by-choice respondents had stronger preferences for the extra-room floor plan than family-minded respondents! And yet over 90 percent of 750-square-foot apartments built in America today will be one bedroom—or none.

When my co-author and I spoke to developers and property management companies about this, we were surprised by their responses. They almost uniformly said they were starting to notice these trends in their own data. The returns on buildings with lots of studio units weren’t as good as anticipated, and family-friendly units were better investments than expected.

Given that most investment in multifamily housing is cautious, slow-moving, and tends to replicate floor plan mixes from prior projects, this response is unsurprising. There isn’t much experimentation in the industry, and with low interest rates, builders didn’t need to deliver highly competitive returns, since the cost of capital was low. This is almost a paradigmatic case of malinvestment.

Unfortunately, it’s malinvestment that will linger in American neighborhoods for decades to come. But we can learn the lesson and improve.

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit could be rewritten to encourage builders to produce a certain number of low-income available bedrooms instead of units, since children are disproportionately likely to be poor. The Build Now Act being considered by Congress could be revised to reward localities for adding more bedrooms, instead of adding postal addresses. The current proposal, which Republicans have supported thus far, subsidizes localities that convert family houses into multiunit apartments, even if the number of residents in the building declines because three children move out and one renting adult moves in.

Localities that set parking requirements per bedroom can repeal those rules or set them per unit instead. Rules allowing age-restricted units to count for affordable-housing mandates can be repealed. Senior citizens are richer than median Americans—we don’t need to subsidize their housing. Housing authorities that build apartments can target bedroom counts over unit counts.

Private builders should adjust their outlook as well. Family-friendly units will sell. At the same square footage, more bedrooms are in demand, and buildings with those units may be cheaper to hold in the long run.

Some in the real-estate industry have already noticed this and have been pivoting quietly. In our report, we’re shouting it from the rooftops: it’s time for family-friendly apartments.

Top Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images

Source link