Across continents, Filipino Catholics have emerged as what Pope Francis once memorably called “smugglers of the faith”: believers who carry the Gospel not by argument but through presence, perseverance, and hope.

During the first-ever Simbang Gabi — a nine-day series of devotional Masses celebrated by Filipino Catholics from Dec. 16–24, leading up to Christmas — celebrated by a pope at St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Francis said in 2019: “I have often said that here in Rome Filipino women are ‘smugglers’ of faith! Because wherever they go to work, they sow the faith.”

Never before were those words more visible than in the experience of millions of Filipinos living and working abroad. What began as labor migration has become an unplanned but unmistakable form of evangelization — carried by ordinary Catholic families whose faith is lived openly, communally, and joyfully.

Faith carried in daily life

For many Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), migration was never intended as a mission. It was about economic survival and responsibility toward families back home. Yet for Fulgencio Abuan, who spent decades working in the Middle East, faith slowly moved from the margins to the center of his life abroad.

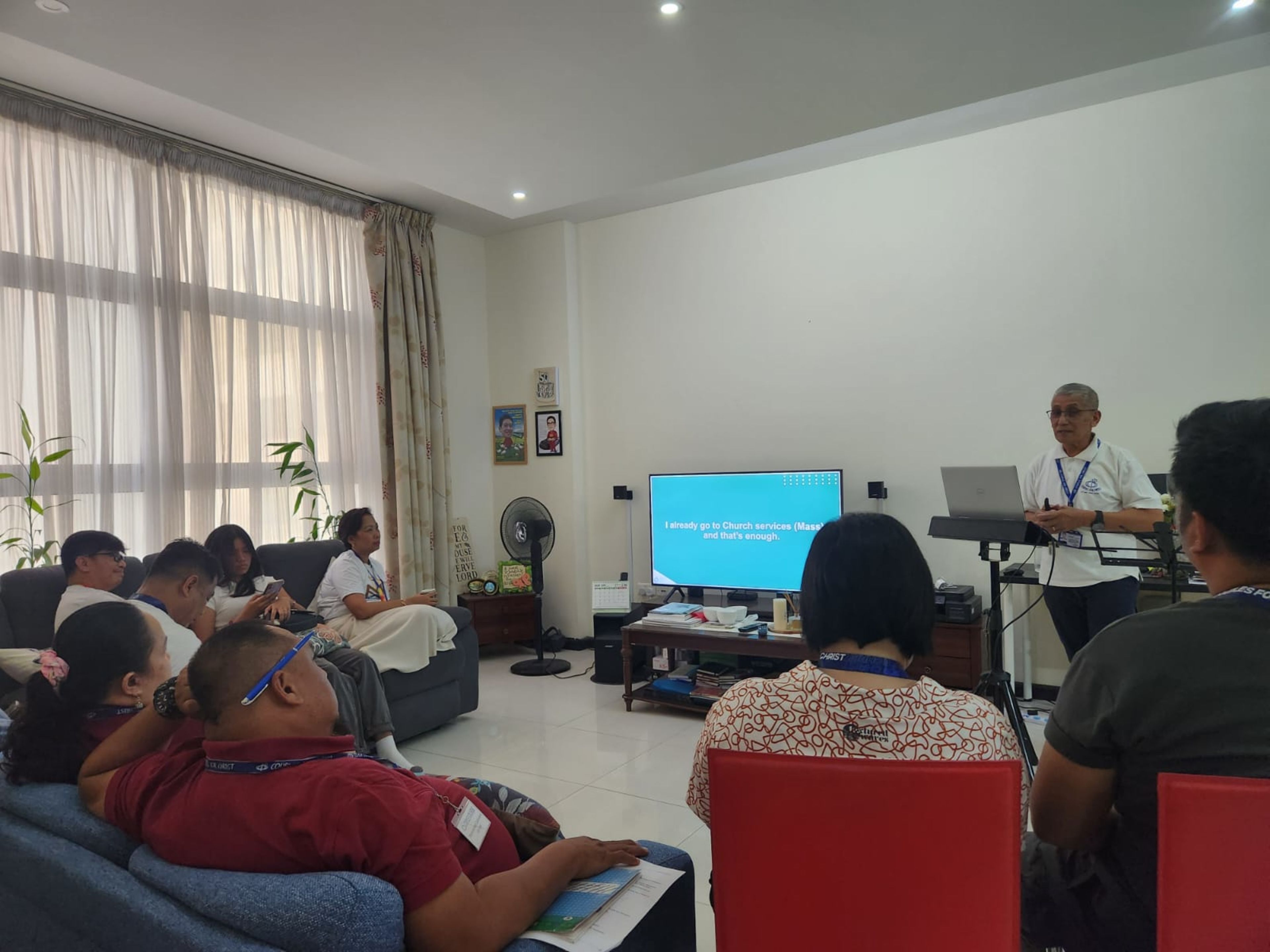

Through encounters with lay ecclesial movements such as Couples for Christ in Bahrain, his faith deepened through regular prayer meetings and formation programs. Personal renewal gradually became shared witnessing.

Members of Couples for Christ attend a formation session during a family day celebration at Sacred Heart Parish in Manama, Bahrain. Lay ecclesial movements like Couples for Christ help Filipino migrants deepen their faith while working abroad. | Credit: Fulgencio Abuan

Abuan recalled that their work was never confrontational or overtly missionary. Instead, it unfolded through presence — welcoming new arrivals, inviting others to prayer, organizing fellowship after Mass, and simply making parish life feel human again. In environments where public religious expression was restricted, Filipinos learned to witness quietly but consistently.

Accidental missionaries

This same pattern is visible in East Asia. In Japan, lay missionary Erlyn Regondon has spent more than a decade working with the Archdiocese of Tokyo, accompanying Filipino migrants, technical trainees, and international parishioners. She observed that many Filipinos who were only marginally involved in parish life back home often become deeply engaged once abroad.

Economic necessity may prompt migration, she explained, but distance from family and familiar culture frequently awakens a deeper reliance on faith. Filipinos step forward as choir members, catechists, altar servers, and parish coordinators — roles they never imagined assuming in the Philippines.

Japanese Church leaders have taken notice. Cardinal Tarcisio Isao Kikuchi of Tokyo has repeatedly acknowledged Filipinos not simply as migrants to be accompanied but as missionary disciples whose presence brings energy, youth, and stability to parish life.

A Church revived by Filipino devotion

In the United States, similar dynamics are at work. Philadelphia Auxiliary Bishop Efren Esmilla, a Filipino shepherd serving the Church in America, has repeatedly witnessed how some parishes on the brink of closure experience a sudden renewal through Filipino immigrants.

As he frequently remarks in pastoral conversations: “Kapag may Pilipino, nabubuhay muli ang parokya.” (“If there is a Filipino, the parish becomes alive again!”)

According to Esmilla, Filipino devotional life — like the Simbang Gabi, Holy Week processions, Marian feasts, and a deeply Eucharistic spirituality — does more than preserve cultural identity. These practices restore joy, participation, and communal warmth. Fellowship after Mass, shared meals, music, and visible hospitality become entry points not only for fellow Filipinos but also for longtime parishioners who had grown distant.

He pointed to concrete examples: parishes that once counted fewer than a dozen worshippers at Christmas now filled again after being entrusted to Filipino-led communities. Rather than closing churches, dioceses increasingly rely on committed lay leaders — many of them migrants — to sustain parish administration, catechesis, and outreach amid ongoing clergy shortages.

Born and educated in the Philippines, and ordained a priest and consecrated bishop in the United States, Esmilla said he believes this renewal is not accidental. Filipino spirituality, he explained, is profoundly Eucharistic and relational. The Mass naturally overflows into service.

Witness beyond the Church walls

That quiet witness sometimes extends well beyond parish boundaries. Father Kenneth Rey Parsad, a recently ordained Filipino priest whose chanting of the psalm during Pope Francis’ Mass at the Manila Cathedral in 2015 drew international attention, recalled being surprised by messages he received afterward — not only from Catholics but also from non-Christians.

“I would get messages saying, ‘I’m not Christian, I’m Muslim — but I was inspired,’” he recalled. For him, the experience underscored that evangelization is not always deliberate. “I just sang the psalm,” he said. “It wasn’t me. It was the grace of God.”

For Parsad, who grew up in a family shaped by migration, the Filipino diaspora’s evangelizing role feels deeply familiar. Faith becomes visible, not as ideology but as lived trust.

The Filipino diaspora by the numbers

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority, an estimated 2.16 million Filipinos were working overseas as of 2023. Most are based in Asia (77.4%), followed by the Americas (9.8%), Europe (8.4%), Australia (3.0%), and Africa (1.3%).

Saudi Arabia remains the top destination, hosting about one-fifth of all OFWs, followed by the United Arab Emirates. Even in countries where Filipinos are a numerical minority, their presence in parish ministries, choirs, and chaplaincies is often disproportionate to their numbers.

Behind these statistics are communities that pray together, share meals, organize novenas, celebrate fiestas, and quietly rebuild parish life wherever they settle.

The Church’s pastoral response

The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) has long recognized the pastoral and missionary dimensions of migration.

Through its Episcopal Commission for Migrants and Itinerant People, the Church supports chaplaincies, lay formation programs, and pastoral accompaniment for migrants facing loneliness, cultural displacement, and the risk of faith erosion.

Host dioceses increasingly collaborate with Philippine Church institutions, recognizing that migrant ministry is not only about care but also about mission. Filipino priests, religious, and lay leaders now serve across the globe — often in regions first evangelized centuries earlier by Western missionaries.

This quiet reversal gives concrete form to Pope Paul VI’s insight in his 1975 apostolic exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi “… the Church is an evangelizer, but she begins by being evangelized herself … Having been sent and evangelized, the Church herself sends out evangelizers.”

A faith once received, now shared

Five hundred years ago, Christianity reached the Philippines through foreign missionaries. Today, history has come full circle. The descendants of those once evangelized now carry the faith across borders, mainly not by design but by the demands of life itself.

As Pope Francis observed, Filipino Catholics “smuggle” the faith through joy, service, and fidelity. Wherever Filipinos gather — for work, worship, or simple companionship — the Church quietly takes root again.

In a world searching for hope, that quiet faith continues to speak.