The legend of Jasper Maskelyne, a British stage magician who helped hide Allied military installations during World War II, has likely been embellished beyond his actual accomplishments.

It would be fair to say that “magic,” in one form or another, played no small part in the Allied victory during World War II.

There was famously “Magic,” the Allied cryptanalysis program conducted by the United States Army’s Signals Intelligence Service (SIS) and the United States Navy’s Communication Special Unit, which decoded more than 4,000 diplomatic messages between the Japanese government and its embassies and consulates worldwide. The codebreaking effort began nearly two decades earlier, before the war, when the US Navy illicitly obtained a codebook from the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Magic may have worked in the Allies’ favor in other ways, too. The Nazi regime was notable for its fascination with the occult; many prominent members of the Third Reich consulted with astrologers or other spiritualists, and it is likely that some battlefield decisions were made on the dubious basis of those predictions—presumably to the Allies’ benefit.

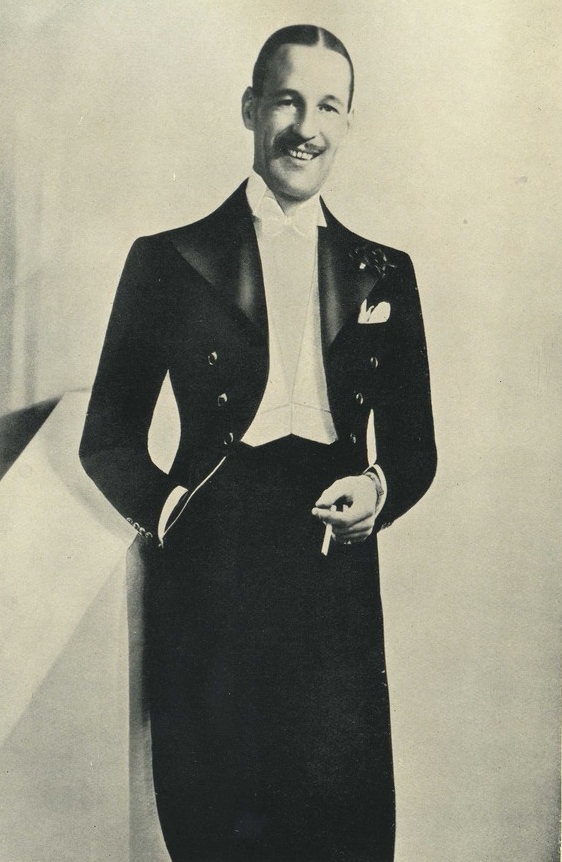

The British largely did not consult with occultists in fighting the war. They did, however, employ the far more practical services of a literal stage magician, Jasper Maskelyne, who had performed to sold-out crowds across the UK before the war.

Jasper Maskelyne, the Great Illusionist

The story of Maskelyne has gained some attention thanks to the newly released Now You See Me, Now You Don’t, which includes multiple references to his work during the war. However, the actual story of this renowned prestidigitator is somewhat more complex—and much of it could itself be described as an illusion, as Maskelyne was once billed as “England’s Greatest Illusionist.”

The often-told story is that Maskelyne and the so-called “Magic Gang” of fellow illusionists aided the British military with a variety of large-scale acts of deception and camouflage. Of course, Maskelyne wasn’t the first or only individual to use sleight of hand, parlor tricks, and misdirection in warfare. There are rumors that Harry Houdini served as a spy for the United States, and German-born British magician and mentalist David Berglas also worked for the American military’s intelligence service.

However, by accounts, Maskelyne was a stage magician like no other. He came from a long line of popular British magicians, and during World War II, he joined the Royal Engineers, offering his skills to the British Army not with card tricks or sleight of hand. Instead, he demonstrated his ability to create effective camouflage and deception.

In one example, he reportedly created the illusion of a German warship on the River Thames in London, using just mirrors and models.

That was enough to convince the military to deploy him to North Africa—perhaps simply to raise morale on the front lines, as he initially spent his time entertaining the troops while they fought the Italians and then the Germans in the Sahara.

Enter the “Magic Gang”

The war might have passed for Maskelyne serving as an entertainer, but he persisted in offering to do more than provide entertainment. His skills were put to the test during the early years of the war, when the British fought the Germans and Italians in the eastern Sahara to protect the strategically vital Suez Canal.

Early in the North Africa campaign, the British military’s commander, General Archibald Wavell, had already assembled “A Force,” which was charged with employing misinformation to the Allies’ benefit. Maskelyne joined this unit and gathered around 14 assistants, including an architect, an art restorer, a carpenter, a chemist, a painter, an electrical engineer, and a stage-set builder from the theatre world. Together, they formed the “Magic Gang,” which quickly created numerous effective illusions to deceive the enemy.

Hiding the City of Alexandria and the Suez Canal

One of the Magic Gang’s biggest tricks was one like no other—concealing the city of Alexandria from German bombers. That effort involved constructing mock night-lights, creating fake buildings, and even a lighthouse and anti-aircraft batteries in a bay 3 miles from the actual city. To the German bombers flying at night, the target appeared as expected, and they attacked it, not realizing that they were dropping their bombs in the wrong place.

For three nights, the trick allegedly succeeded in drawing German aircraft away from the city itself. At least, that’s the story.

Likewise, there are claims that the Magic Gang hid the Suez Canal from Germany’s bombers, but historians debate the fact. It is now believed the gang used a system of 21 searchlights that confused the bombers as to the location of the canal. Coal dust and fuel oil further created a slick on the water’s surface that made it harder to see at night, but not all of these techniques could be credited to Maskelyne.

Operation Bertram and the Art of the Illusion

The Magic Gang’s most significant contribution came during the Second Battle of El Alamein from October to November 1942. In the months leading up to the battle, the Allies launched Operation Bertram, an effort to deceive Germany’s Afrika Korps about the timing and location of an expected Allied attack.

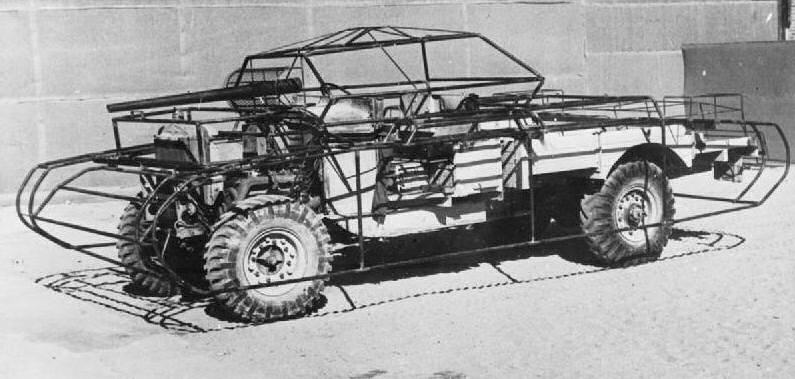

For weeks, the Magic Gang worked painting canvas and plywood to make jeeps resemble tanks, complete with fake tracks. In other cases, tanks were made to resemble trucks to confuse Axis spotter aircraft about where forces were being massed.

In total, the unit created more than 2,000 fake tanks, plus a faux railway line. Simulated radio communications aided the effort, and even the sounds of vehicle movement played over speakers at night. The combined effort was to lead German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel to believe that the Allied forces would attack from the south, even as Allied Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery launched his attack from the north.

The efforts served as a forerunner to the later Operation Fortitude and to the “Ghost Army,” which was intended to convince the Germans that the D-Day landings would be in Calais rather than Normandy.

The Legend Is Far Bigger Than the Truth

Perhaps the biggest trick the Magic Gang pulled was convincing the Nazis—and posterity—of their success.

More than eight decades after the end of World War II, Maskelyne is remembered well within the magician community, but he’s hardly a household name like Houdini. The role of the Magic Gang is not well known, and it is at best a footnote in the history of the North African theater of World War II.

When stories are written, they often paint one of a larger-than-life character—but that could be due to the stage magician understanding that to be a success, you had to be mythical in nature.

In some ways, Maskelyne could be compared to Major TE Lawrence, or “Lawrence of Arabia”—not just because both men were outsiders who fought in the desert, but because (it could be argued) their relatively minor roles were promoted for propaganda reasons and have been further magnified in the decades that followed. Lawrence was likely far less significant in the Arab Revolt than what his official biography stages, although he became almost mythical in popular imagination after Peter O’Toole played him on the big screen.

Maskelyne is much the same. There is no doubt that he was a talented illusionist, but as a magician, his greatest trick was in convincing everyone he was larger than life!

The Magic Gang was just one unit in the much larger A Force, and while it did succeed in creating a fake port around Alexandra, it was impossible to “hide” the whole city. It aided in confusing German bombers, but didn’t save the actual port.

Moreover, the Magic Gang’s role in Operation Bertram was substantial, but it was part of a larger effort undertaken by Brigadier Dudley Clarke and the British Middle East Command Camouflage Directorate, led by Geoffrey Barkas.

That may explain why the Magic Gang disbanded after the operation. If it had been such a superstar effort, surely the Allies would have seen the value in using Maskelyne and his men in Operation Fortitude. Yet they didn’t. Instead, like a great magician, Maskelyne disappeared afterward, and it is unclear what he did during the remainder of the war. In 1948, he moved to Nairobi, Kenya, where he taught driving and magic lessons. He died in Nairobi in 1973.

There has been talk that a feature film could be made about Maskelyne, with Benedict Cumberbatch set to play the colorful magician. That project has yet to materialize, however, so it is unclear when Maskelyne will get another moment in the spotlight.

About the Author: Peter Suciu

Peter Suciu has contributed over 3,200 published pieces to more than four dozen magazines and websites over a 30-year career in journalism. He regularly writes about military hardware, firearms history, cybersecurity, politics, and international affairs. Peter is also a contributing writer for Forbes and Clearance Jobs. He is based in Michigan. You can follow him on Twitter: @PeterSuciu. You can email the author: [email protected].

Image: Shutterstock / A.Pushkin.