250 years ago, Henry Knox transported 60 tons of heavy artillery through 300 miles of ice and snow to Boston—winning General George Washington control of that city.

As Americans deal with a brutal cold snap that has hit much of the Midwest and Northeast, along with heavy snow and even ice storms, it is worth remembering that it could be worse. Even if travel is difficult, we don’t have nearly 60 cannons to transport!

It was 250 years ago this week that Continental Army Colonel Henry Knox completed what was known as the “Noble Train of Artillery,” or simply the Knox Expedition.

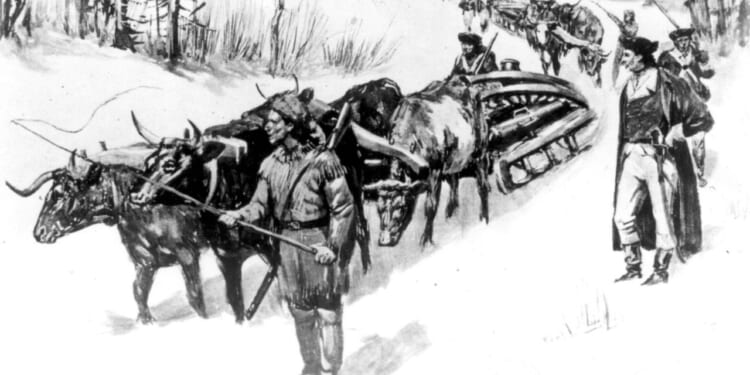

Between November 17, 1775, and January 25, 1776, Knox led a group of just over 40 militiamen and teamsters (civilian contractors) who moved nearly 60 tons of heavy artillery, including heavy brass and iron cannons, over 300 miles from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston.

The successful transport of the artillery enabled George Washington to position the cannons on Dorchester Heights in March 1776, forcing the British to evacuate Boston. That evacuation marked the first major victory for the Continental Army, and it wouldn’t be hyperbole to suggest that the Knox Expedition made it possible.

“Henry Knox’s mission to bring additional artillery from Fort Ticonderoga to the siege lines around Boston was significant in establishing his ability at military logistics and cementing Washington’s respect,” said J.L. Bell, author of The Road to Concord: How Four Stolen Cannon Ignited the Revolutionary War.

Bell noted that the presence of the artillery also sped up Britain’s decision to leave—but did not determine it, as “he had already sought and gained approval from London to leave New England and focus on more promising territory in New York.”

Over the River and Through the Woods…

The other important part of the story is that the Knox Expedition moved the cannons in the very dead of winter over two semi-frozen rivers, through the Berkshire Mountains, across forests and swamps on poor-quality roads, and largely with just horses and ox-drawn sledges.

“It was a major undertaking, and the possibility of failure was very high,” explained Dr. Robert J. Allison, professor of history at Suffolk University. “There probably wasn’t a ‘Plan B.’”

Failure simply wasn’t an option.

Ironically, the brutal weather conditions actually helped Knox. Americans may fear how winter weather can impact holiday travel and shut down roads, but in late 1775 and early 1776, the frozen ground made it possible to haul the cannons across the terrain. Moving the ordnance couldn’t have been done a few weeks earlier, or a month or two later.

“There had to be snow on the ground. It helped to have the frozen roads. During the spring, the ground would have been too soft,” Allison told The National Interest.

That latter point has been noted in later conflicts—notably in the Soviet Union during World War II, and even during the ongoing war in Ukraine. With spring comes mud, and mud bogs down armies. Frozen ground aided the movement of the cannons, and the expedition took advantage of the cold.

Knox understood the importance of freezing the ground. Before crossing rivers at night, he had his men drill holes in the ice so that the water would rise to the surface and thicken it. That was necessary, given the weight of some of the brass and iron cannons.

Knox also took a few chances, and more than a half mile of rope was used to secure the guns to 42 sleds. The heavy ropes were also to allow for retrieval if they fell through the ice.

Sure enough, that did happen when the group crossed the Hudson River, and the teamsters used axes to cut harness ropes to free the animals. That necessitated having men dive in the freezing water to retie the ropes onto the cannons, which were then pulled up.

The “Devil’s Staircase”: The Heartbreak Hill of 1776

“The men were teamsters, not Continental soldiers, and they were paid for their work,” added Allison—who noted that they were used to harsh conditions, but still had their limits.

In one case, artillery needed to be moved down a particularly treacherous and steep descent in Blandford, Massachusetts, known as “The Devil’s Staircase.” The crew initially refused to proceed until resident Solomon Brown and his oxen helped them navigate the descent.

Brown was just one of many “Patriots” along the route who provided aid, including fresh teams of oxen, drivers, and food to support the expedition. The region was known for rough winters, but the conditions may have been just right.

“They didn’t run into such weather that they couldn’t go on,” said Allison. “The cold may have made them want to get there quicker.”

Not a Forgotten Story, but One That Deserves More Attention

Although the Noble Train of Artillery is widely celebrated in the region and was even the subject of a recent historical recreation, the expedition risks fading from history. It hasn’t gained the same level of attention beyond New England as the Battle of Lexington and Concord, and indeed not Washington’s crossing of the Delaware a year later.

However, Bell suggested that its significance won’t be forgotten.

“Except for Valley Forge, I can’t think of a non-battle military action during the war that’s gotten more attention in popular books, commemorations, monuments, and so on,” Bell told The National Interest.

Along the route that the expedition traveled, it has become something of a legend.

“Indeed, the way we usually tell the Noble Train story as the story of an individual, Knox overcoming great obstacles—terrain, weather, sometimes doubters, though there really weren’t any—boils down a complex event into a pleasing narrative, which in turn provides a climax to the narrative of the siege of Boston. That version shows up in lots of recountings of the war,” suggested Bell. “It sticks in people’s minds.”

Bell added that the true history is messier—starting with the British commander already planning to leave well before Knox’ artillery arrived.

“That doesn’t make the Noble Train narrative inaccurate, especially from Knox’s perspective, but that story gets extra weight in most tellings of the siege of Boston because it’s a pleasing, understandable narrative,” Bell continued.

Still, the Knox Expedition should be a much better-known story of the American Revolution, one that was significant for its difficulty and for what it accomplished!

“One of the critical pieces is the role of the teamsters. They weren’t the unionized guys we know today, but they were paid civilians who still took on a difficult job,” said Allison. “The Noble Train of Artillery is one of the major feats of the war. Moving these cannons 300 miles was an ordeal. It is something that you could make a movie about.”

To date, no movie has been made about the Knox Expedition. As for why it isn’t a bigger story, Allison has his thoughts.

“I blame the historians for assuming people know about it,” Allison said. “There is the local pride about it, and it certainly isn’t forgotten where it happened!”

About the Author: Peter Suciu

Peter Suciu has contributed over 3,200 published pieces to more than four dozen magazines and websites over a 30-year career in journalism. He regularly writes about military hardware, firearms history, cybersecurity, politics, and international affairs. Peter is also a contributing writer for Forbes and Clearance Jobs. He is based in Michigan. You can follow him on Twitter: @PeterSuciu. You can email the author: [email protected].

Image: Wikimedia Commons.