Amid all the turmoil involving Harvard — most recently, the Trump administration withholding federal grants and making it the poster child for academic rot — the poison Ivy League’s liquidity problem is worsening. In the past two months, Harvard has turned to the bond markets twice to quickly raise over $1 billion in cash. This follows a scramble in 2024 to raise $1.5 billion through similar bond offerings, which still fell short of its initial target.

Revulsion to Harvard’s institutional wokeness and its embrace of open anti-Semitism by faculty and students was already causing a financial squeeze. As I wrote in November: “Despite an endowment exceeding $50 billion, Harvard had to expedite bond offerings earlier this year to quickly raise $1.6 billion in cash.” Harvard was already in a cash crunch before President Donald Trump announced he was turning off the spigot of federal grants.

Harvard cannot afford to also lose its revenue stream from the federal government — but it’s going to.

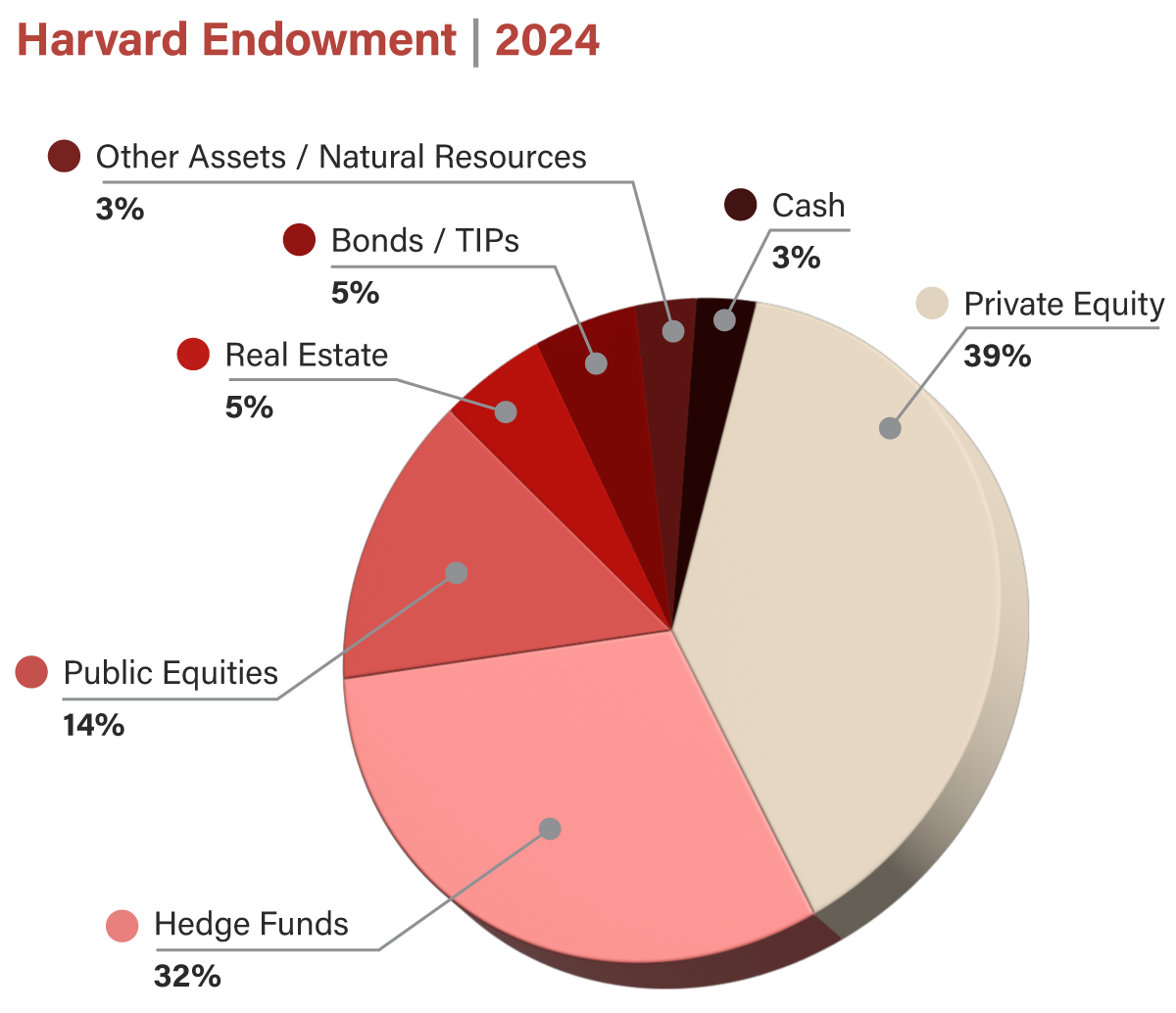

But why is Harvard facing a liquidity crisis if its endowment is truly worth $53 billion as reported? Per published reports as of 2024, only about 20% of Harvard’s endowment is held in liquid assets such as cash, stocks, and bonds. The remaining 80% is tied up in illiquid investments — 71% in private equity and hedge funds and another 8% in real estate and other alternative assets.

While the endowment appears impressive on paper, it produces relatively little usable cash for Harvard — roughly $2 billion annually. And when the market turns south, as it recently has, the financial gimmickry underpinning these investments can actually consume cash.

A liquidity crisis

In early March, Harvard announced it would return to the debt markets to raise $450 million in cash via tax-exempt bonds. Barely five weeks later, the university had to rush another $750 million bond offering — this time in taxable bonds — bringing its total new debt to $1.1 billion. According to the Harvard Crimson, this pushes the university’s total debt burden to $8.2 billion.

Despite its wealth, Harvard relies on billions of dollars in non-tuition revenue each year to pay its bills. In the fiscal year ending June 30, 2024, the university reported $6.5 billion in operating revenue. Of that, just 21% came from tuition. Nearly half — 45% — came from philanthropic donations, while federal grants comprised another significant portion.

With the donors starting to hold their noses and sit on their wallets, Harvard cannot afford to also lose its revenue stream from the federal government — but it’s going to. The Trump administration recently announced that it would suspend $2.2 billion in federal grants.

Consequences of ‘wokeness’

Meanwhile, Harvard President Alan Garber remains committed to admissions policies that appear racially discriminatory, as well as remaining steadfast in his commitment to keeping Harvard a welcoming space for foreign nationals who are hostile to Jews. As reported by CNN:

Harvard refused to eliminate diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, ban masks at campus protests, enact merit-based hiring and admissions reforms, and reduce the power of faculty and administrators the Republican administration has called ‘more committed to activism than scholarship.’

Despite Garber’s repugnant principles, they also invite more problems for the school. Like Bob Jones University before it, Harvard’s policies are racially discriminatory. Bob Jones University lost its tax-exempt status for racially discriminatory admissions policies and prohibiting interracial dating. Now Harvard may suffer the same fate:

The Internal Revenue Service is making plans to rescind the tax-exempt status of Harvard University, according to two sources familiar with the matter, which would be an extraordinary step of retaliation as the Trump administration seeks to turn up pressure on the university that has defied its demands to change its hiring and other practices.

Donors have long benefited from itemized tax deductions for their munificent donations to Harvard’s operating budget. If Harvard loses its tax-exempt status, donations will no longer be tax-deductible. While I do not doubt that donors had a genuine passion for Harvard while donating to the school, the tax ramifications were also a motivator. Losing the tax deductibility of donations would constrict that revenue stream even further.

Out of cash, out of time

Ultimately, Harvard’s multibillion-dollar bond offerings may barely serve as a Band-Aid if federal and donor revenue streams dry up. However illiquid the famed endowment may be, the university may soon be forced to start selling what assets it can. According to New York Post columnist Charles Gasparino, “Wall Street execs who follow the college endowment business say it’s only a matter of time before Harvard starts selling what’s liquid in its portfolio, i.e., stocks.” He is also trying to confirm if Harvard is, in fact, already selling liquid assets held by the endowment.

Harvard cannot borrow its way out of its cash crisis. For now, the university scrambles for more loans to cover bills and meet payroll. But lenders will not endlessly bankroll unsecured debt from a tarnished institution bleeding cash. A day of reckoning approaches.