Roy Kuhlman (1923–2007) worked during the mid-twentieth century, when graphic design was defined by experimentation. He designed seven hundred book covers and jackets for Grove Press, a publisher of modernist literature, psychology, Eastern religion, sociology, and radical politics. Kuhlman also worked on the design for Evergreen Review, Grove’s cultural magazine. In Roy Kuhlman: Reluctant Modernist, Steven Brower, who is a graphic designer himself, offers a selection of well over two hundred book covers designed by Kuhlman. These attest to his extraordinary ability for rendering “narrative abstraction,” as Steven Heller dubs Kuhlman’s style in his introduction to the volume.

Robert Alexander “Roy” Kuhlman was born in 1923 in Fort Worth, Texas, the son of an automobile mechanic and a nurse. Roy was born with a hole in his heart, a condition that made it hard for him to be physically active. After his family relocated to California, he took to drawing, and at Glendale High School he studied under Ernest Tonk, a painter specializing in landscapes of the American West. Despite serious continuing health-related difficulties, Kuhlman earned scholarships to study first at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles and then at the Art Students League of New York in 1946.

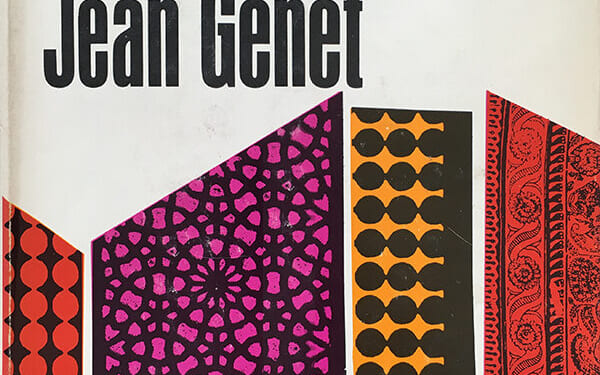

In 1951 Kuhlman was looking for work in New York when he visited Barney Rosset, the publisher of Grove Press. As Brower writes, “Grove offered American readers their first introduction to the European dramatists of the Absurd, the French Surrealists, the San Francisco and New York ‘Beat’ poets, and the New York Abstract Expressionists.” Rosset was not impressed with Kuhlman’s portfolio until two pieces of abstract art slipped out of Kuhlman’s folder. “This is what I want!” Rosset exclaimed. Rosset, a friend of Willem de Kooning, was publishing avant-garde literature, including Krapp’s Last Tape by Samuel Beckett, Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby Jr., and The Balcony by Jean Genet. These experimental books needed suitably avant-garde covers, and Kuhlman was just the man for the job. Although Kuhlman and Rosset had a long and productive working relationship, the two men were never friends. “Never do business with friends,” Kuhlman said. “They’re more trouble than they’re worth.”

Kuhlman said his work was influenced by “the strong, simple” style of the Abstract Expressionist painter Franz Kline. Kuhlman’s second wife, Gilda Hannah, elaborated:

He thought symbolically! He hit the mark all the time but actually some covers were not meant to be symbolic. Some were strictly designs. They had no meaning whatsoever. But as a general rule for how to make a cover, he would just say, “Well you glance at the book, you take some things out of it that you can symbolize.” But there are some books where you can’t think of anything as a symbol. Then you have to start thinking a different way. He was very good at that. And he had a good eye for compositions.

Kuhlman used brightly colored abstract and geometric forms, which he combined with clean gothic typefaces or roughly sketched, expressive letterforms. In the words of Steven Heller, this new “transcendent modernist aesthetic” made Kuhlman’s covers “timeless,” even as the field of graphic design was rapidly evolving: in the early 1950s, other modernist book-jacket designers, such as Paul Rand and Alvin Lustig, were abandoning figurative, realistic scenes and experimenting with symbolic and expressionistic motifs for their book covers. Despite the stiff competition, Heller wrote in his New York Times obituary for Kuhlman that the artist’s

minimalist graphic vocabulary was entirely his own. He avoided literal representation, because he said he could not really draw well. Instead, his random color patterns and amorphous shapes seemed totally independent from the texts they were illustrating. He rarely read the manuscripts before designing the covers, and yet every image was eye-catching and posterlike, designed to draw attention to the books on the shelves.

Kuhlman was not a full-time employee for Grove, so he had to find other ways to supplement his income. Describing himself as a “job jumper,” he worked for advertising agencies, movie studios, and Columbia Records, among other places. Yet his most timeless work remains the covers he made for books such as The Spirit of Zen by Alan Watts and The Theater and its Double by Antonin Artaud.

Kuhlman was known as a great teacher and an inspired artist but could also be notoriously stubborn and uncompromising: collaboration with colleagues was difficult under “Kuhlman’s Law,” which consisted of him “listening to what they had to say, then doing it his way, later convincing them it was the right way for the job.” Judging by the sheer number of brilliant designs collected in Roy Kuhlman: Reluctant Modernist, we are lucky that he managed to have his way.