Chicago law firms have found a new way to get paid at taxpayers’ expense: suing the city for alleged police misconduct. The suits are draining hundreds of millions from Chicago’s coffers at a time when the city can’t afford to lose a dime. Voters should hold their leaders accountable for enabling this racket.

For years, Chicago has led the nation in overturning supposedly wrongful convictions. This has resulted in a windfall for law firms—both those suing the city and those hired by the city to settle cases. Since 2000, Chicago has paid over $700 million in settlements to criminal defendants who claim to have been framed by police, at least $138 million of which has gone to the city’s outside counsel. Chicago alone was responsible for more than half of the nation’s exonerations in 2022.

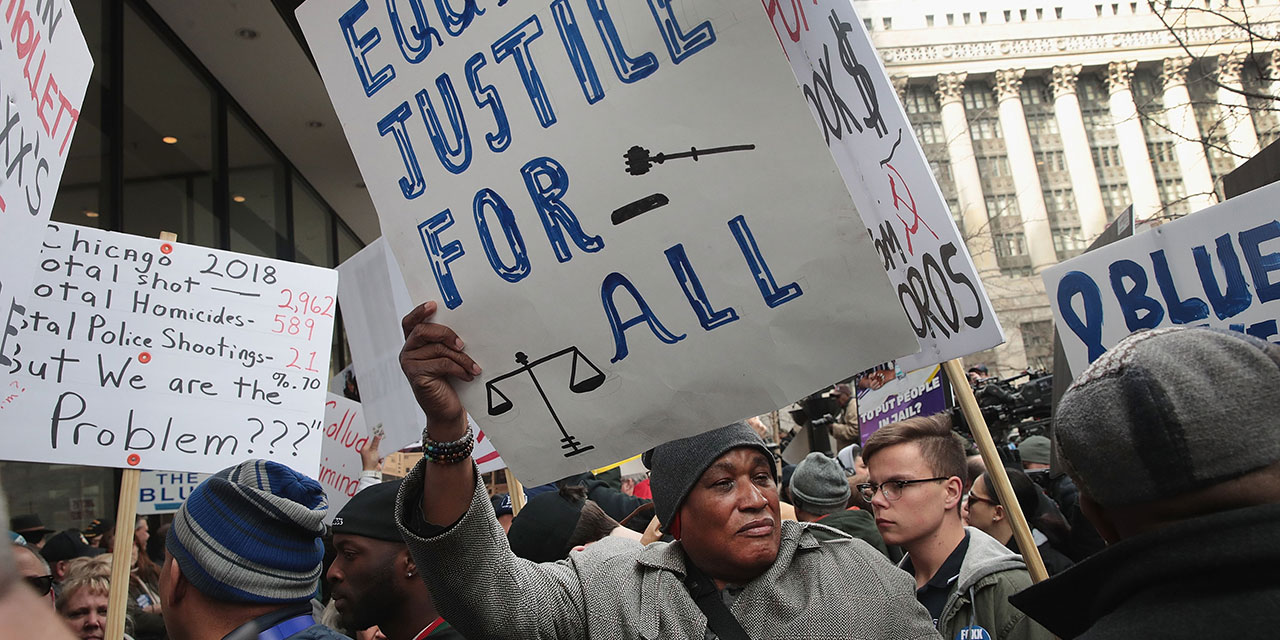

The pattern continued this year. In March, a local jury awarded $120 million to two men who served 16 years in prison before their convictions were overturned. On the same day, the Chicago City Council approved $280,000 to settle a claim from an activist injured in a violent protest from 2020 that left 18 officers wounded.

These big-money settlements have prompted some Chicago law firms to specialize in city claims. In 2022, just one firm settled cases totaling $42 million of the $117 million that the city paid out that year. Based on a standard one-third contingency fee, the lawyers likely reaped a handsome $14 million.

City leaders are to blame for this swindle. During her eight-year tenure as Cook County state’s attorney, Kim Foxx prioritized the rights of criminals over the law-abiding and law enforcement. Her policies effectively encouraged local law firms to represent plaintiffs in civil rights suits against the Chicago Police Department, often resulting in mammoth, taxpayer-funded settlements.

Foxx’s most direct contribution to this racket was her expansion of the so-called Conviction Integrity Unit. Housed within the State’s Attorney’s Office and later renamed the Conviction Review Unit, it reviewed felons’ claims of innocence. In practice, the unit released prisoners—often based on policing irregularities rather than exculpatory evidence—who subsequently sued Chicago and were awarded large settlements.

In fact, Foxx often contributed to these lawsuits’ success by recommending that courts grant “Certificates of Innocence” to released inmates, who could then use the certificates as evidence in suits against the police department and city. In some cases, Foxx’s office acknowledged that the certificates did not reflect the recipient’s innocence. Her office sometimes cooperated in the release of inmates, including alleged murderers, who were likely guilty of their crimes but nevertheless secured multimillion-dollar settlements and verdicts.

For example, Gabriel Solache and Arturo DeLeon Reyes, both Mexican illegal immigrants, were convicted and sentenced in 2000 for a double kidnapping and double murder. In 2017, a court overturned their convictions after the men claimed that a detective had beaten them to induce a false confession. Without the confession, prosecutors couldn’t meet the burden of proof and dropped the case, even as they firmly believed that the two men committed the heinous crimes.

Because the men were likely guilty, the Cook County state’s attorney had, for years, opposed granting Solache and Reyes certificates of innocence. In 2022, however, Foxx withdrew her office’s opposition, allowing the men to use the certificates in their federal civil cases against Chicago.

Foxx also defended Assistant State’s Attorney Michelle Mbekeani, then the head of the Conviction Review Unit, after she was accused of a conflict of interest. Mbekeani had operated a business linking inmates with wrongful-conviction claims to private attorneys. When questioned by a judge, Mbekeani gave, in the judge’s words, “duplicitous, incomplete, evasive, and untruthful” answers. She resigned from the CRU in June 2024 after only six months on the job.

Foxx’s successor as Cook County state’s attorney, former judge Eileen O’Neill Burke, has taken a more moderate approach than her predecessor. She believes, for example, that the state’s attorney’s office should support Certificates of Innocence only in cases with “concrete, irrefutable evidence” of innocence.

But Burke will face headwinds in her efforts to reduce expensive lawsuits against the police department. In 2020, Illinois passed the SAFE-T Act, which creates stricter use-of-force policies, limits officer discretion in certain arrests, and expands officer liability. Coupled with new Chicago Police Department restrictions on police pursuit, these regulations present a ripe opportunity for criminals to bring baseless claims against law enforcement. Likewise, the CPD’s consent decree with the State of Illinois in 2019 contains several hundred paragraphs of recommendations and presents further lawsuit opportunities.

The consent decree has failed to improve the city’s relationship with the Chicago Police. As City Journal senior editor Charles Fain Lehman found, it has not had an appreciable effect on police conduct or public perception of the city’s police department. In fact, some evidence suggests that it may have worsened Chicago’s horrific crime problem.

By imposing onerous restrictions on police conduct, the decree also puts officers in harm’s way. According to Police Superintendent Larry Snelling, since 2020, 330 police officers have been shot at and 38 have been shot, injured, or killed. By contrast, police shootings—one of the bases for the consent decree—have declined.

In keeping with other changes to Chicago’s criminal justice system, the consent decree has been a windfall for lawyers. The firm that serves as the consent decree monitor, responsible for reporting on CPD compliance, has billed the city $19 million—35 percent above original estimates. It’s little wonder, then, that the firm routinely reports poor compliance.

In Chicago, a network of academics, community activists, attorneys, and politicians have turned criminal-justice reform into a cash cow for criminals and their lawyers. Whether because of their worldview or their wallets, they don’t care that their policies divert hundreds of millions of dollars from public needs and let violent criminals become millionaires upon release. Fixing the problem will require holding its enablers in city government accountable.

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images