The Petit Palais has a history of exhibiting Scandinavian masters whose works are barely known outside of their own countries, such as Sweden’s Bruno Liljefors, about whom I wrote for Dispatch last February. Now the museum is devoting an exhibition to Finland’s Pekka Halonen (1865–1933), whom Annick Lemoine, the director of the Petit Palais, dubs a “lighthouse in Finnish art” in the exhibition’s catalogue. Almost all of the paintings in the show come either from private Finnish collections or Helsinki’s Ateneum museum, which co-curated the exhibition. Speaking for myself, Halonen is a revelation, especially because my knowledge of Finland had previously been limited to Len Deighton’s spy novel Billion-Dollar Brain.

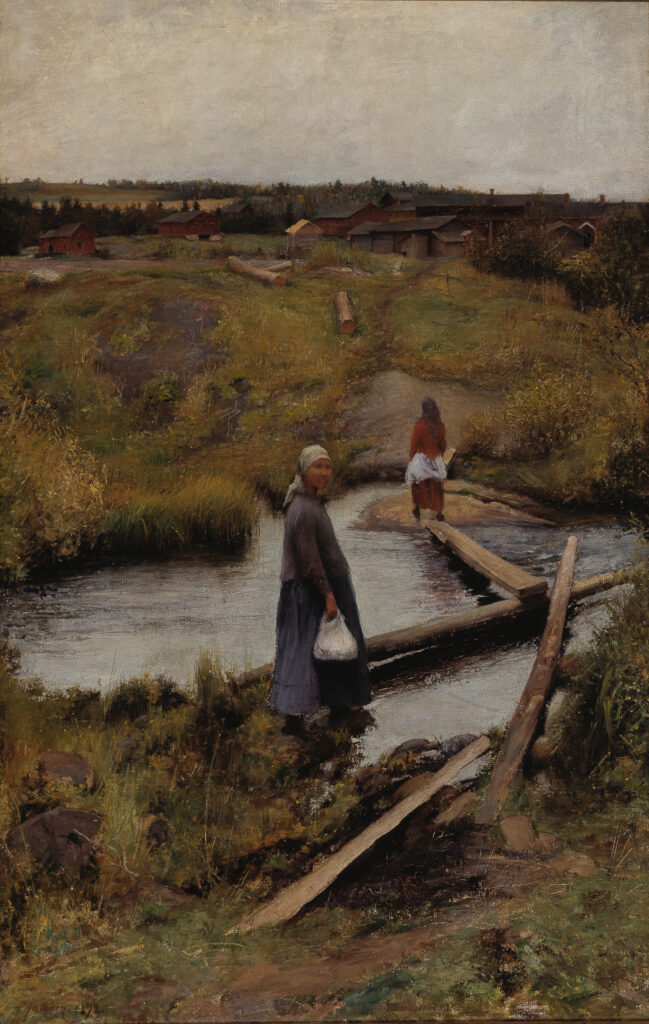

Introduced to painting by his father, Pekka Halonen was trained at the Society of Drawing and Fine Arts at Helsinki. Halonen went on to study in Paris, first at the Académie Julian in 1890, and then at the Académie Colorossi in 1893. Such sojourns in the world’s art capital were considered essential for any aspiring European artist. In Paris, Halonen was greatly impressed by Paul Gauguin and transferred to the Académie Vitti so that he could study with the master, who had just returned from Tahiti. Aside from Primitivism, he learned from other current French movements, including Post- Impressionism and the Nabis, but he was also influenced by the Japonisme then in fashion and the early Italian Renaissance, which he studied not only at the Louvre but also in Italy. Nordic painters of his generation studying in Paris also learned from Jules Bastien-Lepage’s naturalistic style, and Halonen was no exception, as is evident in The Shortcut (1892). The oil shows two women crossing a lake on a makeshift bridge, walking towards a village in the background across a muted, green meadow. One woman turns to look out towards the viewer, but her face is too blurry to make out.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes’ classicism as well as Gauguin’s influence can be seen in After the Music Lesson (1894), showing Halonen’s sister-in-law Aino holding a guitar. Halonen came from a musical family. His brother Heikki, a professional musician, was the subject of The Violinist (1900), and the composer Jean Sibelius was a close family friend. In 1895 Pekka married Maija Mäkinen, a pianist who often played for him while he painted. Halonen himself performed with the kantele, a traditional Finnish stringed instrument similar to a zither which is played on a table. In 1891 the artist Eero Järnefelt painted Halonen playing the instrument next to a table with a bright-red lampshade against a subdued red sofa; the warm color scheme is reminiscent of Vuillard. Halonen’s The Kantele Player (1892) shows a musician whose eyes seem almost in a trance as he strums his runes. Emerging from the black shadow, he could be straight out of a seventeenth-century painting. Something similar can be said of Halonen’s Self-portrait (1906), in which the artist, dressed in a V-necked, tieless white shirt, looks like he’s playing the part of Hamlet.

Halonen was a Finnish patriot at a time when Finland was under Russian rule. Finland had been part of Sweden for centuries, but the country was ceded to Russia under the Treaty of Hamina in 1809, and Finland became an autonomous grand duchy within the Russian Empire until 1917. A pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair of 1900 was an opportunity to exhibit Finland’s economic and cultural riches. The painter Albert Edelfelt was put in charge of the fine-arts section. Edelfelt called on other Finnish painters, including Halonen and Akseli Gallen-Kallela (both members of the nationalist “Young Finland” group), to send works to the World’s Fair, some of which are on view here. Heikki Halonen played first violin in the concert at the Finnish pavilion while Pekka presented The Lynx Hunter (1900), a large panel showing the subject stalwartly skiing up a hill, rifle in hand, in search of his prey.

The exhibition also includes works of other artists, many of whom were friends of Halonen. The Archipelago View, a charming picture by Venny Soldan-Brofeldt, the wife of the writer Juhani Aho, is a striking depiction of sailing boats on a blue sea. Soldan-Brofeldt, Aho, Sibelius, and Halonen and his growing family were members of an artistic community on Lake Tuusula in southern Finland. They were inspired by the British Arts and Crafts movement but also by the Swedish feminist Ellen Key, who promoted the introduction of beauty into everyday life.

Halonen wrote that while he was happy to have seen Paris and its splendors, nature, as well as the seasons, was his main source of inspiration. The house where he and his wife lived (called Halosenniemi), his garden, and the forest gave him the most marvelous paintings in the world, he said. In 1913, he depicted his studio. Despite the guns on the red-pine wall, a steel cover by the fireplace with a relief of a sitting boy holding his knees suggests a sense of peace and cozy comfort. The same year, Halonen portrayed his beloved fruit in Tomatoes with the bright colors he had learned from Fauvist and Post-Impressionist artists. Autumn Colors of two years earlier shows the season’s fallen russet leaves under stark, shorn branches and cloudy skies.

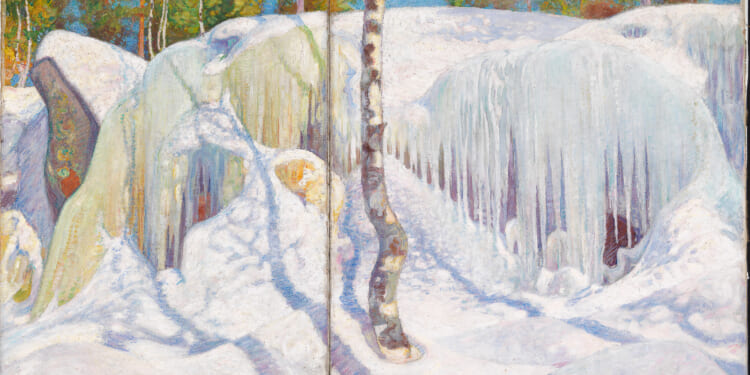

Halonen, being Finnish after all, was most at home as a painter of winter scenes. Winter Landscape at Myllykylä (1896) shows a sweeping snow-draped riverbank with a contrasting forest of evergreens in the background; it is a fitting choice for the exhibition’s catalogue cover. Rock covered with Ice and Snow (1911) features enormous icicles beginning to melt as winter turns into spring, as signaled by the warm green of the treetops visible in the background. No other painter has described snow in all its nuances with such painstaking loving care as Halonen. As we prepare for the season of “Let it Snow,” this brilliant exhibition seems to chime like sleigh bells in a winter wonderland.