Throughout Church history, particularly during the 1–5th centuries, many heterodox teachings about the physical body and the flesh emerged. A notable set of ideas infamously held by the Gnostics, Manichaeans, and Marconians (amongst others) was dualism—the central theme being that the body was a barrier, something to be overcome, rather than holy and made in the image of God, as Genesis supposes.

Whilst this heresy was anathematized over 1500 years ago, it is one of the easiest to fall into, especially when reading the Pauline letters. Even today, many subconsciously hold that the mystical is divine and the physical sinful, despite sin existing both in spirit and in flesh. No one rejected his soul for its envy, yet many reject their flesh for its gluttony. This is not the biblical nor the patristic anthropological position.

It is no surprise that remnants of this heresy still linger in modern Christianity—it can seem that Scripture itself constantly condemns the flesh. However, to interpret such verses as Romans 6:19 as dualist would be to miss their point; throughout the Pauline writings, flesh (or sarx in the original Greek) does not necessarily mean the physical body in a literal sense—it represents human weakness or mortality.

Since the Fall, we have been limited by our fleshly desires. That isn’t to say our physical body is evil, but that because we act on desires of flesh so impulsively, it is the pinnacle of our weakness. This is what makes asceticism so powerful—one discards human carnality in order to live in body and soul in accordance with God’s will. In doing so, you aren’t so much limited by your flesh but rather in closer unity with it.

To assume flesh equals bad would be to undermine the glory of the incarnation—God became man, bridging the gap between God and man and unifying the two. If physical body is bad and God became physical, is that not blasphemy against the Son?

A patristic quote that well demonstrates this is towards the end of chapter 21 of St. Augustine’s On Continence, a short but theologically weighty epistle to the Manichaeans. Augustine says: “No one ever hated his own flesh, but nourishes and cherishes it, as also Christ the Church.” He makes it clear that, not only should we not “hate” the flesh, but we should also “nourish” it, even comparing one taking care of one’s own body to Christ cherishing and taking care of the Church. Given the writing’s theme of addressing heresies such as dualism, it certainly exemplifies that disregard of the body is akin to a Christless life; if Christ did not nourish the Church, could man not nourishing the body—which 1 Corinthians 6:19 describes as “the temple of the Holy Spirit”—be considered equally disordered?

However, it is important to distinguish between “cherishing” the body and submitting to bodily temptations. In the life of the good Christian, the soul ought to be the master of the body, not vice versa.

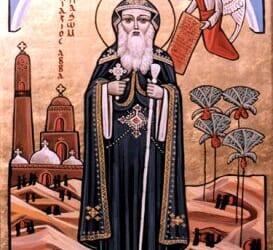

In his 1970s work “Communion of Love,” Fr. Matthew the Poor, a contemporary Coptic monk, writes on the union of body and soul: “The body, when sanctified by obedience to the Spirit, becomes a true partner in the spiritual journey.” This expresses not only a strong unity between natures, but also the spiritual discipline required for the flesh. The body shall pass, and it is the act of placing your soul in the hands of the Lord that will ultimately restore it.

Thus, “cherishing the body” is not falling to temptations of the flesh—lust, gluttony, or sloth—it is using your body as a tool to serve Christ and your neighbor. Galatians 5:16 says, “But I say, walk by the Spirit, and you will not gratify the desires of the flesh.” For one to “gratify the desires of the flesh,” he must be void of the Spirit. But to control and tame the desires of the flesh under the guidance of the spirit? That is true asceticism.

St. Irenaeus of Lyons also speaks of the human body in his ante-Nicene work, Against Heresies, a writing addressing Christians who, like Manichaeans, were being influenced by Gnostic ideas of dualism, which were being spread using an appeal to logic (as Aristotle would say, an appeal to logos) to distort the message of the gospel.

He affirms in Book 4, Chapter 20, that “The life of man is not in the soul alone, but in the whole man, that is, in body and soul.” This was in refutation of the teachings of Valentinus and Marcion, whose systems denied the fullness of the deity of the incarnate Word, and that salvation was for the soul only, similar to the methods rejected in On Continence.

The quote emphasizes the unity of the body and soul, particularly in the context of glorification. The quote follows, “For the glory of God is a living man,” a direct reference to Genesis and the creation of man, and the doctrine that we, man, are made directly—physically and spiritually—in the image of God and the heavenly hosts. It fundamentally pushes back against the idea that the body is a prison, or something that needs to be escaped. God’s plan—creation, fall, redemption, and eventual exaltation—was for spirit and body. Christ redeemed humanity by taking on the flesh, not by condemning it, nor purging it, but by reunifying the divine Ousia and the human body.

I would go so far as to argue that maintenance and love for the body is a moral obligation under a Christian moral perspective. Whilst the Coptic Church offers no centralized doctrine on the matter, the concerns of the Church are those of life, not death—the promise of Christ is that he who believes and remains in communion with the Body of Christ is to inherit eternal life. Christ is truly life as Christ is truly flesh; therefore, to disregard the flesh of the Lord would be to disregard His life.

So, whilst a common misconception is often held on the nature and role of the physical body, such views collapse under the weight of Church tradition and the sanctity of the Incarnation. The body is neither inherently evil nor an object to be indulged—it is to be disciplined, nourished, and ultimately glorified in Christ.

Photo by Alexander Grigoryev on Unsplash