This year marks a half-century since the acute phase of New York City’s fiscal crisis. It began in February 1975, when a default by a state-backed housing authority alarmed the bankers who regularly lent to the city, prompting closer scrutiny of New York’s own finances. In April, the banks stopped extending credit to cover the city’s chronic deficits. That led to a state takeover of city finances in June and, finally, a federal guarantee of the state rescue plan in December.

The crisis still sparks both ideological and practical debate: Was it the banks’ fault—for lending too much, or for cutting off credit? Or was it the city’s fault, for borrowing beyond its means? Did the reforms that followed usher in an era of harmful austerity or broad-based prosperity? Was the outcome a bailout, a punishment, or both?

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

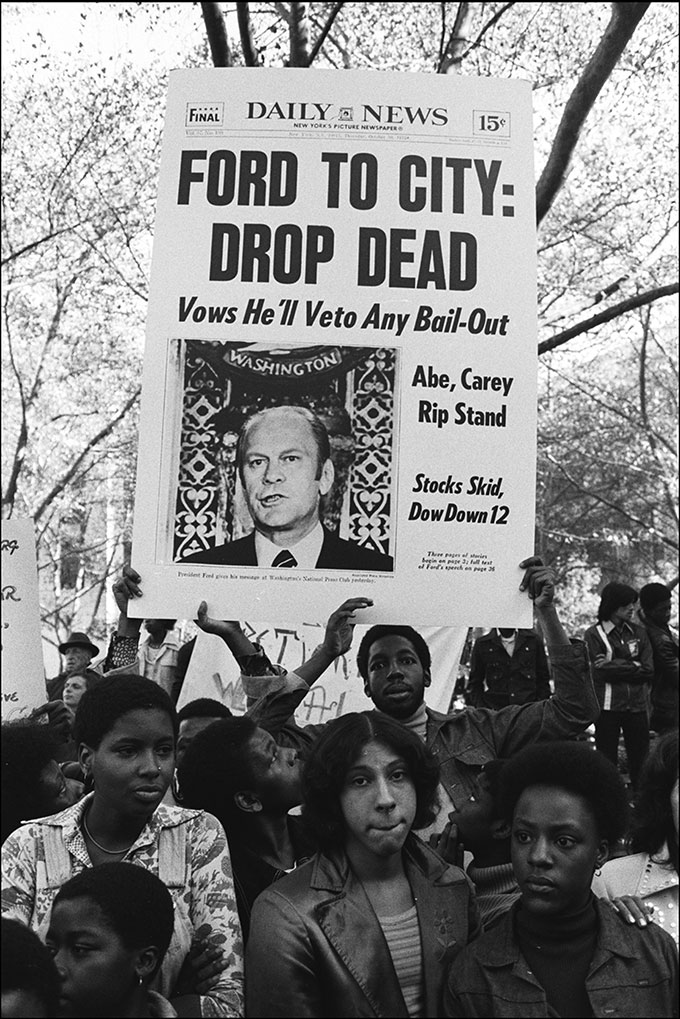

We’ve both recently attended a screening of a new documentary on the crisis, Drop Dead City. The title comes from the famous Daily News headline paraphrasing President Gerald Ford’s initial refusal to rescue New York in October 1975: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.” As with many famous quotes, Ford never used those exact words—though what he did say was close enough. Directed by Michael Rohatyn and Peter Yost, Drop Dead City blends newly unearthed archival footage with clips and fresh interviews featuring key figures from 1975, including union leaders and financiers.

Nicole Gelinas: E. J., I’ve always wondered—where were you when the events of 1975 unfolded? Were you following them closely at the time, or did you come to the topic later—and if so, how, when, and why? And what was your initial impression of Drop Dead City? Did it strike you as riveting or dull, accurate or off the mark, relevant to today or a relic of the past?

E. J. McMahon: I was completing my junior year and studying for final exams at Villanova (one year ahead of a future pope, as it turns out) when the crisis burst into the open in the spring of 1975. I had returned for my senior year by the time of the famous “Drop Dead” headline that fall. Of course, much else was happening in the spring of 1975—not least the fall of South Vietnam and its aftermath. And in September, just a month before giving the speech that inspired the Daily News headline, President Ford was the target of two assassination attempts within just over two weeks—events that Drop Dead City doesn’t mention.

If you grew up in the metropolitan area, as I did—in the suburbs of Westchester and Putnam counties—New York City felt like the center of the known universe. It was certainly the center of the local news media universe. From a very young age, just from the 15 minutes of local TV news I watched each morning before Captain Kangaroo, I got the impression that some guy named “Mayor Wagner” must be more important than the president.

As a viewing experience, Drop Dead City was first-rate, in my book—an entertaining and still-relevant portrayal of what now feels like ancient history. The directors made a smart choice in focusing on a single year, 1975, rather than getting bogged down in the sprawling backstory of the fiscal crisis, which stretched back to the 1960s and wasn’t fully resolved until around 1980. Of course, as a Boomer, I’ll admit to having a nostalgic bias toward anything centered on 1975.

Unlike a Ken Burns–style, multipart deep dive, Drop Dead City forgoes scripted narration and tells its story through the recollections of former officials, retired city workers, and journalists, as well as contemporaneous news coverage and real-time comments from key players—people like the late Felix Rohatyn, chair of the Municipal Assistance Corporation (MAC) and father of one of the documentary’s directors.

In the entertaining clips of 1975 interviews with everyday New Yorkers—men, women, and kids in the street, as opposed to union members facing layoffs—the dominant emotion seems less like anxiety over the fiscal crisis and more like excitement about being on TV. The crisis was real and deadly serious, but in an era of peak local television and peak newspaper circulation, much of the outrage portrayed in the documentary also feels performative. Amid the mounting alarm—verging on panic—in City Hall and the State Capitol, most New Yorkers were simply going about their lives, largely unconcerned about the city’s financial future.

The anger of union leaders—especially sanitation workers, firefighters, and cops—was real. But the worst scenes of garbage piling up on the streets were the result of a three-day wildcat strike by the sanitation union ahead of the July 4 weekend. They didn’t reflect daily life across the city, at least not in 1975. And as one Drop Dead City interview shows, not all tourists were even aware of the “Fear City” leaflets distributed by the police union. The most consistently outspoken union leaders, like Victor Gotbaum of DC 37, the city’s largest civilian union, and Ken McFeeley of the PBA, clearly knew where the cameras were. But protests and publicity stunts aside, the deepest strains on city services came later, during the period of fiscal retrenchment in the years following the 1975 crisis.

So, to sum up: as a production, Drop Dead City told an interesting story—entertaining, well-crafted, and creatively assembled from archival footage and interviews with surviving principals (most of whom, sadly, have since passed away). But to answer another part of your question—did Drop Dead City offer a fully accurate picture of what was happening and why? My take on that is more mixed.

Before getting to that, though, I’d be curious to hear the impression this film made on someone from a different city and a younger generation—though in your case, Nicole, someone who also came to this documentary fresh from researching and writing an award-winning history of transportation policy in New York City. That story overlaps with the fiscal crisis in key ways and features some of the same figures who play prominent roles in Drop Dead City.

Gelinas: Yes, E. J.—regarding those interviews, it was especially poignant to see the late Dick Ravitch, the real-estate developer who helped engineer the city’s rescue in the 1970s and, a few years later as MTA chairman, led the revival of the transit system, speaking in vivid color from his kitchen. I still catch myself feeling—as I did for so long—that you can just reach out to these people whenever you have a question. But the reality is, for some of them, you can’t anymore.

Though I came along a generation or so later and grew up much farther from New York City, my formative experience of it, and my impression of the movie, weren’t so different from yours. When I was a kid, I loved newspapers—all newspapers—and my dad, who worked for the Cambridge Fire Department, would bring home the New York tabloids from the now-defunct Out of Town News kiosk in Harvard Square. The New York news of the 1980s was so much more dramatic—and more dramatically presented—than the Boston news, and the personalities were so much larger. I, too, saw the mayor—Ed Koch, in my era—as this almost cartoonishly important national figure, which, in many ways, he was.

Thinking about it from a fiscal perspective today—which does, I promise, tie back to the movie!—Robert Wagner, your formative mayor in the late 1950s and early 1960s, derived much of his power from the city’s fiscal position within a specific postwar state and national context. His administration, including his multiple-office-holding appointee Robert Moses, expertly leveraged this environment. Wagner controlled what would today amount to tens of billions in federal funding for road infrastructure and public housing. He also benefited from the natural growth in property tax revenues that came with a still-expanding local economy, which allowed him to formalize public-sector collective bargaining and to begin increasing social spending, without the city experiencing immediate fiscal strain.

Nearly three decades later, Koch didn’t derive his powers from fiscal strength but despite its absence: for most of his mayoralty, which ran from 1978 until 1989, the city remained under the state receivership imposed in 1975. The mayor couldn’t approve an infrastructure project or sign a labor contract without the permission of MAC, the state-controlled financial control board. In retrospect, some of the stunts Koch pulled, like suggesting that wolves be placed in subway railyards to deter graffiti vandals, and his perceived coziness with real estate—supporting the Westway landfill highway development project, say, after initially running for office opposing it—were ingenious hacks, meant to wield influence without holding the purse strings. And they sometimes worked: his public pressure on subway graffiti helped push the state-run MTA to act.

What happened between Wagner and Koch was, in compressed form, the subject of Drop Dead City. The story of 1975, in few sentences: starting in the 1950s, New York City’s spending began to outpace its tax revenues. In the 1960s, rising social spending collided with middle-class flight to the suburbs. For a long time, the city’s banks covered the gap, lending money to maintain the illusion of a balanced budget. But in 1975, for various reasons, the banks shut off the spigot. New York had to turn first to the state, then to the federal government, for a bailout—one whose repercussions still echo today.

What struck me first about the film was what it says about New Yorkers’ civic curiosity and engagement: the early May weekend screening at the downtown IFC Center I attended was sold out. The crowd was a mix of older New Yorkers—many of whom have likely lived in Greenwich Village for decades—and people in their twenties, likely including some NYU students.

My second impression was the quality of the archival material. As the directors noted during the Q&A, archival producer Frauke Levin unearthed and viewed reels of film—not video!—that haven’t been touched since the 1970s. That freshness, as opposed to standard stock footage, really makes a difference. I especially enjoyed the clips from the BBC special that explained New York City municipal debt to a global audience—including a great shot of the old, then new, Twin Towers. It speaks to how important New York City was, and still is, that the BBC felt compelled to dive in here.

Some of that vivid archival footage raises important questions about accuracy and context. Yes, the scenes of garbage piling up and EMTs responding to DOA crime scenes against the backdrop of sharp 1975 budget cuts and a soaring murder rate are gripping. But are they sufficiently contextualized—and does that context matter? What does Drop Dead City get right, and where does it fall short?

McMahon: There was a lot of talk in the movie about how wonderful New York’s municipal government had once been—how its expansive and generous social policies made it a city where poor immigrants could take root and thrive. Naturally, there were frequent references to free tuition at CUNY. And plenty of praise for New York as a big union town—emphasizing how special and important the unions were, and how they had secured generous living wages for public employees.

If you came to this with only general knowledge, you could be forgiven for letting the city off easy. Yes, Drop Dead City makes clear, New York’s spending and debt had gotten out of hand. As Stephen Berger, who directed the state’s bailout-era Emergency Financial Control Board, points out, “there were no f—ing books” that accurately recorded the city’s spending and debt.

You learn in passing that Nelson Rockefeller—the former longtime Republican governor of New York, who, irony of ironies, was vice president by 1975—had arguably been a godfather of the crisis, if not the godfather. Still, you might come away with the impression that the city’s leadership, at least, meant well—that the fiscal collapse was, as the regrettable title of an otherwise indispensable early history by the late Charles Morris had it, The Cost of Good Intentions. That the real villains were a cabal of proto-Reaganites in Washington and their hypocritical buddies in banking. Which is just an anachronistic and simplistic view.

The focus on 1975 is both a strength and a weakness in this respect. To be fair, it would have been hard to convey a fuller, more nuanced story in a 1-hour-and-43-minute documentary aimed at a general audience.

But I think a few missing details would have helped place the events of 1975 in clearer context—showing that the city was not simply a well-meaning victim of larger forces. The generous wage and benefit packages won by municipal labor unions beginning in the 1950s were a significant part of the problem—not the whole story, but a major factor. Mayor Wagner had granted the unions collective bargaining rights as a way to weaken Tammany Hall, and he secured his political base by indulging them at contract time. They steamrolled his successor, John Lindsay, when he tried to resist some of their demands during his first term—and Lindsay more or less gave up trying. As Victor Gotbaum memorably puts it, the political power unions had begun amassing under Wagner meant they were “electing their own bosses”—in Albany as well as at City Hall—and they showed little concern for the creative accounting those bosses used to fund their contracts.

Gelinas: Yes, and the line in the film about Rockefeller never spending a night in the Governor’s Mansion in Albany, because his own homes were so much nicer, got big laughs at my screening—especially paired with the image of him strapping into his private plane. And of course, it’s accurate and fair: he was so far above the rest of us—even above other governors—that he either didn’t grasp, or didn’t care about, the real-world, long-term consequences of his spending decisions. His governing strategy was to pump money—endlessly—into New York during the late 1960s and early 1970s in an effort to quell social unrest. But exactly how to pay for all the spending was never seriously asked or answered. That was his approach to transit, too. So, what were these “dodgy methods” by which the city financed itself, with Rockefeller’s implicit blessing?

McMahon: Mayors Abe Beame (in office during the crisis), Lindsay, and Wagner had built—and kept adding to—an enormous financial house of cards, more or less in plain view of the governor, their constituents, and the news media. In fact, it was Rockefeller who, in 1962, signed the legislation that opened the floodgates to recurrent deficit borrowing. While “there were no f—ing books,” it didn’t take an accountant to see what was going on. Newspaper pieces from the 1960s were already sketching the damning outlines of overspending and economic decline in real time.

Once the crisis hit in earnest, with the real prospect of insolvency and bankruptcy, it wasn’t just Republicans in Washington who resisted a bailout. At the time, both houses of Congress had been controlled for decades by large Democratic majorities, further expanded by the post-Watergate wave in 1974. Yet even Tip O’Neill, the House majority leader in 1975, reportedly doubted whether a bailout could garner enough support. Read the transcripts of the October congressional hearings on New York’s plight, and you’ll find the Democratic junior senator from Delaware, Joe Biden, wondering aloud how to explain to his constituents why New York, of all places, deserved an injection of their tax dollars.

Yes, William Simon had been an investment banker who profited handsomely from municipal-bond sales before becoming the Treasury secretary who opposed federal aid. And yes, Ford’s aides—Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney—were ambitious young Midwestern Republicans who relished the chance to say “no” to the Big Apple. But at the core of Ford’s resistance was a common-sense fear of creating a moral hazard—and he was hardly alone in that view.

Gelinas: The issue of moral hazard—if we bail out New York, who else will we be bailing out?—has echoed for five decades now, often in ways the players of 1975 likely never anticipated. One of the most striking scenes in Drop Dead City shows “regular people” bringing their paper bonds to the city’s redemption window, terrified that New York wouldn’t honor them—and that they’d lose a large chunk of money they had counted on for retirement. The banks didn’t lend directly to the city; they bought its bonds and then sold them to the public.

And of course, the plight of “regular” people is always used to justify broader bailouts. Another of the film’s most compelling scenes, from a historical perspective, is the secondhand account of Mayor Beame looking out from Rockefeller Center across the vast expanse of New York City and telling himself that the federal government wouldn’t allow a long-term bond default—because “New York is too big to fail.”

The phrase “too big to fail” wasn’t yet part of the common vocabulary—it wouldn’t be, until the first major bank bailouts of the mid-1980s—but Beame’s remark raises a key question: who was really being bailed out? The city itself, or the banks that had lent it money and then sold that debt to the public? Did the federal government’s eventual rescue set the stage for a decades-long pattern of risky bank and investor behavior, driven by the assumption that Washington would always intervene when the stakes were high enough?

It’s not hard to trace a line—perhaps a slightly jagged one—from the New York bailout to the Reagan-era rescue of a major commercial bank in 1984, and then to the 2008 financial crisis, when the federal government bailed out banks to the tune of trillions of dollars. That, in turn, helped fuel the national dislocations and elite resentments that gave us President Trump—twice.

Ironically, it was the Wall Street boom of the early 1980s that helped drive New York City’s fiscal, economic, and eventually public-safety revival. The financialization of the U.S. and global economy funneled tens of billions in new income into the city—and billions in new tax revenue—making the 1975 crisis feel like a distant memory. But looking back from the vantage point of 2008, it’s clear that while much of that profit stemmed from real innovation, a significant portion also came from the correct assumption that the federal government would step in with a bailout if needed. And the beginning of that mindset was 1975.

But enough about finances—let’s turn to the people. What did you think of Drop Dead City’s portrayal of some of the key personalities, E. J.?

McMahon: Beame is portrayed as hapless—and that begins in the opening minutes of Drop Dead City, with a news clip from his January 1974 inauguration. As the 5’1” mayor steps up to the podium and begins his speech, two aides in the background notice that the gooseneck microphone is angled well above his head. So one of the aides—like everyone else on stage, she’s noticeably taller than Beame—briskly walks to the podium, crosses in front of him, and lowers the mic while he’s mid-sentence.

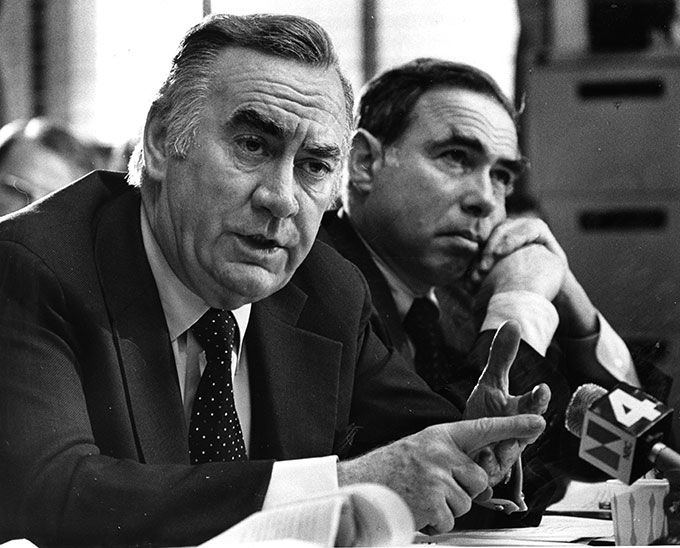

It was a clever and fitting visual metaphor. Beame was in over his head by that point—but as Wagner’s former budget director and Lindsay’s comptroller, he shared significant responsibility for the crisis he inherited. As for Governor Hugh Carey, while the documentary implicitly casts him in a positive light, it arguably doesn’t do enough to highlight his indispensable role in the drama. That would have been hard to convey, admittedly—Carey often came across as colorless and wooden in public, even though he was far more relaxed and effective behind closed doors, where he did his best work.

Drop Dead City’s frequent use of clips featuring Felix Rohatyn is understandable, and not only because of his son’s role in the production. Rohatyn was a smooth, sophisticated global financier; his credibility and intelligence led Carey to bring him in to chair MAC. Early in the crisis, he was the most charismatic figure on the management side. Still, a viewer seeing this without prior knowledge of the story might be forgiven for thinking Felix was the star of the show.

Gelinas: Yes—as someone who had only read about Beame in newspaper articles, seeing that moment with the aide adjusting his microphone cast him in a different, perhaps more sympathetic, light. No matter what comes after, you should at least get to enjoy your inauguration day!

The movie left a few loose ends—saved for the 2026 summer blockbuster sequel, I’m sure! First, it never mentions that, despite all the talk of post-1975 austerity, city spending is much higher today than it was back then, whether in inflation-adjusted or population-adjusted terms. Tax levies are higher, too.

We’ve been able to afford both guns and butter on a municipal level—and on a national level—for a long time, under administrations of both parties. Since the mid-1990s, the city hasn’t really been forced to make tough decisions about what to prioritize in a crisis: public safety or social services? Infrastructure or smaller class sizes?

So let me leave you with big concluding questions, E. J.: Could this happen again? Is it possible that New York could one day lose the confidence of its bankers and bondholders once more? And how would such a scenario play out differently today? We no longer have local banks lending the city money, but institutional bondholders investing through bond mutual funds. And we no longer have local financiers like Felix Rohatyn, but global figures like Jamie Dimon—far less connected to New York City’s politics, personalities, and policies.

And my second question: Did the 1975 crisis, and the national response to it—you mention Biden’s comments, which captured the anti-city sentiment of the time—help pave the way for the Reagan administration? The film hints at this with a great clip of then–California Governor Ronald Reagan cheerfully lecturing everyone on fiscal responsibility.

As president, of course, Reagan cemented his tough persona by firing the air traffic controllers during the 1981 strike. The movie, meanwhile, presents New York’s municipal labor unions—especially the teachers’ union—as heroes in the end, for ultimately agreeing to purchase the city’s newly state-guaranteed debt for its pension fund. That moment may have been the public-sector unions’ last major PR victory before Reagan’s decisive anti-union action later that year.

I don’t think the city unions or their members were villains—everyone has to make a living. At our Q&A, one woman even stood up to thank the directors for not portraying the unions as the bad guys, which they weren’t. But I’m not sure they were heroes, either. Purchasing state-guaranteed debt and agreeing to wage deferrals—all eventually repaid—aren’t the same as accepting work-rule changes and other reforms that would have made municipal services more efficient and cost-effective. Remember, Lindsay first got into trouble with the unions simply for wanting police to work more nighttime hours, when the crime actually happened.

McMahon: To take your points in reverse order—I wouldn’t villainize organized labor, either. Unions exist to advocate for their members and, in the public sector, to maximize their political influence where they can. It’s not their job to manage long-term fiscal policy. That’s the responsibility of elected executives and legislatures, and in this case, they failed.

As for the argument that New York City’s near-bankruptcy marked a turning point that helped accelerate the rise of Ronald Reagan and a more conservative Republican Party—I’m skeptical. Urban liberalism had largely discredited itself by the late 1960s, and Jimmy Carter’s 1976 nomination signaled a shift toward a more moderate Democratic Party after the McGovern debacle in 1972.

New York City’s 1975 crisis couldn’t—and wouldn’t—unfold the same way in the twenty-first century. As you noted, the bond market is vastly different now. Beyond that, the state has outlawed many of the specific abuses that led to the crisis, including the rolling over of short-term debt to cover recurring operating deficits.

But the city is still fully capable of spending itself into a deep hole. In fact, we saw a recent example of how it might happen. After the Covid-19 outbreak in spring 2020, city revenues plunged so rapidly that then-Mayor Bill de Blasio sought state approval to issue billions in deficit bonds—essentially reenacting the original sin of the fiscal crisis. Then-Governor Andrew Cuomo refused, and the issue faded for two reasons: first, the federal government, starting under Trump and continuing under Biden, flooded state and local governments with cash; second, New York’s own revenues were buoyed by a Wall Street boom no one had anticipated.

But if the past 50 years have taught us anything, it’s that economic conditions and fiscal indicators can turn south quickly. Under Mayor Eric Adams’s proposed fiscal 2026 budget—which he shamelessly labeled the “best ever”—the city faces projected budget gaps of $8 billion to $10 billion over the next four years, according to independent fiscal monitors. After years of heavy spending, the structural imbalance in New York City’s finances is large enough to wipe out the current reserve cushion if tax revenues stagnate for even a few years.

At the national level, even setting aside the risk of federal aid cuts, the budget bill passed by House Republicans with President Trump’s backing would effectively raise the already-heavy state and city tax burden on closely held professional partnerships and financial-sector firms—posing a serious threat to New York’s competitiveness.

Just as the municipal bond industry has been transformed, most of the big banks that once dominated New York’s economy had disappeared or been consolidated beyond recognition by the late 1990s. Jamie Dimon may have a global focus, but with JPMorgan Chase recently building a new 60-story headquarters on Park Avenue, the firm still has a major stake in the city’s future. The securities industry today is far larger, more decentralized, and more diversified than it was 50 years ago. Yet New York continues—for now—to hold a sizable critical mass of the industry, even as its share of financial-sector employment has been in steady decline for two decades.

It’s hard to name a present-day equivalent of Felix Rohatyn who could lend the skills and stature needed for a city fiscal rescue—if and when one becomes necessary. But I wouldn’t bet that such a person isn’t out there. New York’s major real estate families loom larger than ever in civic life, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing—they’re literally rooted here. And there’s still a core of committed New Yorkers among the global business class. If more of them were willing to stick their necks out and push for the policy and management reforms needed to make the city more competitive, we might worry less about reliving some version of 1975 in the 2020s or 2030s.

Gelinas: Thank you, E. J.. And, as you note in a recent City Journal article, Drop Dead City contains a minor error in stating that MAC debt was finally paid off in 2008. In fact, it wasn’t—the Bloomberg administration, with state approval, refinanced it, and that refinancing was refinanced again a few years ago. The city won’t finish repaying it until 2034. It’s fitting, in a way, that New York addressed a debt crisis with more debt, and revealing that, for a long time, the strategy worked. But with national bond markets now wobbling—yes, Trump is the immediate cause, but more the detonator than the explosive material itself—how long can it keep working? And what happens if it stops?

Top Photo: Unemployed New Yorkers seeking financial assistance, December 1974 (Peter Keegan/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Source link