Dorothy Day was a lay missionary. She was not a member of a religious order (although she did become a Benedictine oblate); rather, she was a convert to Catholicism who completely embraced the religion to guide her everyday existence according to the Church calendar, liturgy, prayers, and Mass. She believed wholeheartedly in Jesus’ proclamation, according to Luke, that “Blessed are the poor.” She rejected the dominant social and economic philosophies of her time—Socialism, Communism, Capitalism—choosing instead to embrace a philosophy—Personalism—that, she believed, best matched the human with the Maker.

Born to a lower middle-class family in Brooklyn, her father was a journalist who moved his family around as he found different jobs in Oakland and Chicago. Dorothy was baptized and confirmed in the Episcopal Church. As a teenager, she read the Bible and developed a firm foundation of religious faith.

But when she attended the University of Illinois, she began to question her religious foundation. She gravitated toward the radical political philosophies in America during World War I and became an anti-war activist and quasi-atheist. She identified herself as a Socialist, writing for Socialist periodicals, following in her father’s footsteps as a journalist.

Arrested for protesting for women’s suffrage in Washington, D.C., she spent a short time in Occoquan prison, where she became familiar with the guidance and solace of the Psalms. Although her radical philosophy had turned her away from Christianity, she could not turn away from God’s ultimate plan.

Living in New York, she slowly became attracted to the Catholic Church. Dorothy had a variety of love affairs and several marriages; she even experienced the tragedy of aborting a child. In the mid-1920s she was in a common law marriage with Forster Batterham when she became pregnant; he did not want the child, but she did, and she named her daughter Tamar.

Having the baby inspired in Dorothy religious feelings, and she wanted the child baptized in the Catholic Church. Dorothy soon followed. The Catholic Church, she realized, was the church of the poor, which drew her to it. Dorothy began to be inspired by the New Testament, St. Augustine, St. Teresa de Avila, and St. Therese of Lisieux. She recounts her journey toward converting to Catholicism in her autobiography, The Long Loneliness.

Dorothy met Peter Maurin, a lay member of the De La Salle Brothers and a philosopher on behalf of the European peasantry, in New York in 1932 during the height of the Great Depression. They jointly decided to publish a paper: The Catholic Worker. The first issue appeared in May of 1933. Dorothy and Peter also began to sponsor places for the poor to go for food and shelter, Houses of Hospitality, and even farming communes.

During the 1930s, Catholicism became second nature to her; she experienced the mystical body of Christ, living her faith wholeheartedly and praying the rosary and daily office every day. She gravitated toward the liturgy and divine office of the Benedictines, embracing Benedictine hospitality. She was also fascinated by the Franciscans and imitated them in her view of voluntary poverty, pacificism, and mercy toward others. She also studied Ignatius Loyola and his Spiritual Exercises.

Dorothy became highly critical of capitalism and socialism, choosing instead the philosophy of distributism. The broad gap between the rich and poor disturbed her, and she wanted to see more people able to own their own property. She also embraced the philosophy of personalism, defined as, as she wrote in a 1936 issue of The Catholic Worker:

We are working for the Communitarian revolution to oppose both the rugged individualism of the capitalist era and the collectivism of the Communist revolution. We are working for the Personalist revolution because we believe in the dignity of man, the temple of the Holy Ghost, so beloved by God that He sent His son to take upon Himself our sins and die an ignominious and disgraceful death for us. We are Personalists because we believe that man, a person, a creature of body and soul, is greater than the State, of which as an individual he is a part. We are Personalists because we oppose the vesting of all authority in the hands of the state instead of in the hands of Christ the King. We are Personalists because we believe in free will, and not in the economic determinism of the Communist philosophy.

(Zwick & Zwick, 1999, p. 22)

Dorothy’s personal philosophy, reflected in her abundant writings, involved human dignity, free will, obedience to God, working for God, subjecting oneself to God’s will, availability of property for all, and adequate wages for each individual to live a life in conformity to God’s will. She spoke out against society’s exploitation of the poor, governments spending money on arms and war, advertising that tries to fool the poor into seeking what they don’t need, and employers refusing to pay adequate wages to the poor for his/her work.

For Dorothy, one should live one’s life according to the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount. She also believed in Holy Poverty, giving what one possesses to others, as found in the Gospel of Matthew:

For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me. (Mt 25:31-46)

Dorothy anticipated Vatican II, wishing for the liturgy to be brought to the people, to conform to their needs. She rejoiced in the reforms, wanting the Mass to better conform to the poor.

She supported worker’s causes, strikes, and unions like the United Farm Workers; she opposed child labor; she opposed environmental destruction; she was worried that agribusiness would omit the poor farmers and farm workers. In some sense, Dorothy opposed the dangers of economic and social modernization.

She was pacifistic even during World War II, which put her on the FBI watch list. She was opposed to the Vietnam War. Many Catholic Workers burned their draft cards. She believed in taking Christ’s words in the Sermon on Mount, to turn the other cheek, literally. War corrupts youth, she believed, as well as soldiers, helping to cause the horrors of the 1960s, such as the sexual revolution and the widespread experimentation with drug use. War and conscription, she argued, exploits the poor.

Dorothy was a prolific writer, penning not only her many articles and opinion pieces in The Catholic Worker, but a variety of books: On Pilgrimage, a journal of the year 1948 living on a farm in West Virginia with her daughter Tamar and her husband David Hennessey; The Long Loneliness, her autobiography (1952); Loaves and Fishes (1963), about the Catholic Workers Movement; Thérèse, a biography of Thérèse of Lisieux (1960); The Eleventh Virgin, fiction from 1924; and Little by Little: The Selected Writings of Dorothy Day (1983).

Dorothy is an example of a Catholic lay missionary, a person who dedicates her life to the Great Commission, spreading the word and love of God to others, strangers, sacrificing themselves to ensure that God’s kingdom triumphs over evil, secularism, and disbelief. She was famous, of course, but there have been many others just like her who have spent their lives in relative anonymity working on behalf of Jesus. Their work often goes unobserved—but not completely. As Paul wrote in his letter to the Philippians: “For it is God who works in you to will and to act on behalf of His good purpose” (2:13).

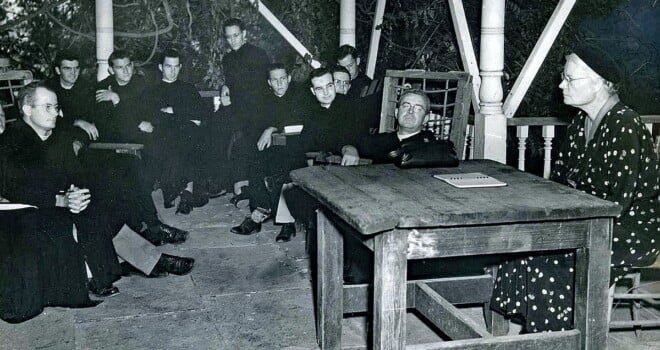

Photo from Wikimedia Commons