The greatest US vulnerability to China’s rare earth dominance is a political and economic system that slows development around a national security priority.

One would have to have been completely removed from the discussion of current domestic, international, and geostrategic affairs over the past year to have missed the at least co-starring role of rare earth minerals (REM) in ongoing domestic and trade policy upheavals. Those policies and their upheavals are the end product of rapidly changing calculations involving equally fast-evolving variables, all of which come down to this: dominance in sectors vital to national military and economic security, such as communications, energy, and defense, requires national control of reliable rare earth supply chains. As of now, and for many decades before, the United States has not had either control or reliability. It is not an exaggeration to believe that future US national independence and economic prosperity depend on gaining both control and reliability in supply.

What Rare Earths Are and Why They Matter

In brief, rare earth minerals are a set of seventeen elements, a subset of thirty-six minerals that the United States Geological Survey (USGS) classifies as critical minerals. REMs are characterized not by geologic scarcity but by the rarity of concentrated and economically viable deposits available for processing. They can be further divided into light rare earths (LREEs), with relatively low atomic numbers, and heavy rare earths (HREEs), with higher numbers. Both LREEs and HREEs are indispensable for numerous critical consumer and defense technologies, including smartphones, electric vehicles (EVs), computer hard drives, advanced microchips, lasers, jet engines, radar, drones, nuclear submarines, and night vision goggles. In short, economically rational access is indispensable for the functioning of modern society and the defense establishment that protects it.

How China Gained Control

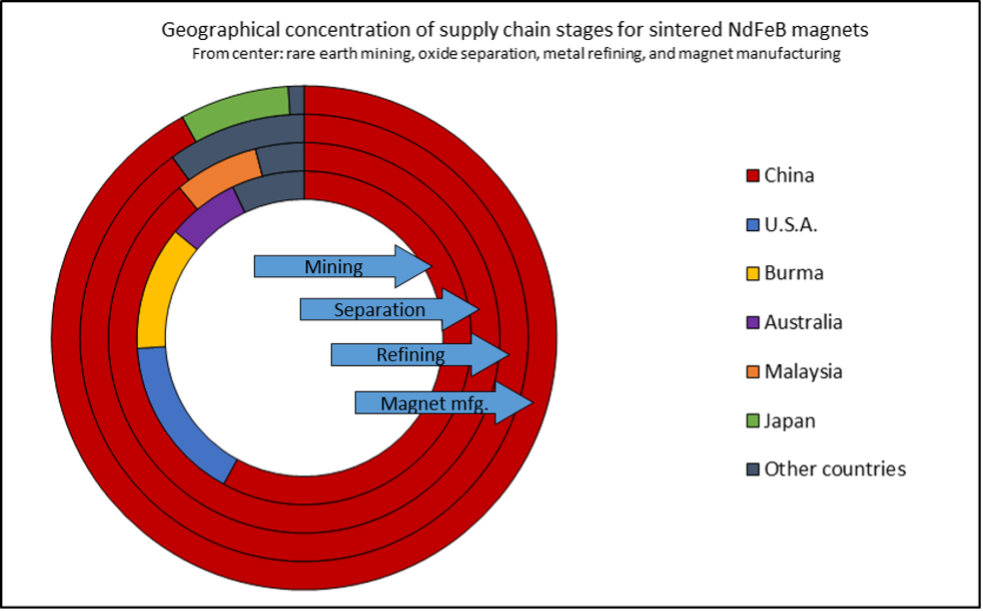

By now, it is well known that China has developed a virtual stranglehold over REM supplies and the specialized magnets that are a sine qua non for smartphones and fighter jets. That status is the product of intentional industrial policy dating back decades before either smartphones or today’s fighters were developed. In 1987, on his “Southern Tour,” Deng Xiaoping famously said, “The Middle East has oil. China has rare earths.” Since Deng spoke those words, Chinese state actions have consistently sought to build and reinforce dominance over global rare earth supplies and, critically, the manufacture of the specialized magnets they make possible. According to the United States Geological Survey, since that time, China has developed into the principal producer of rare earth minerals. In the 1990s and 2000s, China rose to become the principal producer of REMs, reaching a peak of virtually 100 percent of production in 2010, while accounting for 30 percent to 50 percent of known world reserves over those periods. That strategy has progressed despite the identification of significant deposits elsewhere, which have held China’s share to 49 percent in 2024, according to the USGS. China has achieved this dominance by focusing on downstream processing and manufacturing, undercutting global market pricing in each. The US Department of Energy (DOE) illustrated this dominance in 2022:

While the DOE report is three years old and based on data from 2019, the situation has changed little in the years since. That is because the Chinese centralized industrial policy includes state subsidies, low labor costs, and virtually no environmental standards or enforcement. For example, its subsidies have historically included direct production subsidies to miners and refiners based on production, export controls, and industrial consolidation into state-owned enterprises, which are supported by tax breaks, land use rights, and research and development funding. The environmentally challenging processing and refining of REMs have meant lax or nonexistent environmental controls have historically permitted favorable production costs of Chinese suppliers. While China has very recently instituted new and potentially costly environmental controls, the implementation and effectiveness of those are still to be seen, and the advantages of its existing market dominance remain. The end result is that while China has until now accounted for approximately 40 percent of world reserves (more on that in a subsequent article), it represents well over 80 percent of processing and over 90 percent of manufactured outputs such as neodymium magnets. Other countries, including the United States, continued to send their mined ores to China for processing and manufacturing.

US Vulnerabilities and What Comes Next

Ongoing Chinese dominance rests on two things. In the short term, perhaps two to three years, the existing mature and complete supply chain means China will very likely remain a monopoly supplier of both REM processing and manufacturing outputs. A continued ability of the Chinese central government to dominate and manage the supply chain depends on the will or lack thereof within the United States and other Western governments to develop and finance industrial policies and investments throughout the supply chain, from mining REMs to their processing to the manufacturing of specialized end products. There is no lack of raw material potential in the United States and potential international partners. While there is only one operating mine in the country, the Mountain Pass Mine, several others represent the potential for complete raw material independence. Projects are being developed by Idaho Strategic Resources and American Rare Earths. In the case of the latter, total rare earths production is estimated at approximately 20 percent of China’s total reserves, and that is after only approximately 25 percent of the reserves have been assayed.

As such, access to raw material reserves is not the principal US vulnerability. Rather, the differences between the United States and Chinese political and economic systems, and their facilitation or complication of development along the full supply chain, represent the greatest obstacles to be overcome. The US system includes potential veto holders on development at the local, state, and national levels. Development and production are overwhelmingly determined by private market risk and reward, shaped but not dictated by government policy. China’s central government has exploited these systemic differences, becoming a potential threat to US economic and national security. While steps forward have been made, beginning with Executive Order (EO) 13086 under the first Trump Administration and more recently EO 14241 on strengthening the defense industrial base and increasing domestic mineral production, the steps taken to date do not yet represent a comprehensive answer to the directed development and control of China’s authoritarian system. In a subsequent installment, I will explore the historical precedents for US industrial policy and what lessons they may hold for navigating current US REM vulnerabilities.

About the Author: Robert Sweeney

Robert W. Sweeney is the Managing Partner of Accelex Resources, an energy and minerals venture investor, and a senior partner of Montague-York, a government relations firm in Washington D.C. A former bank CEO with a thirty-five-year career in international finance, he holds a certificate in Clean Energy Systems from MIT, a Master’s in International Affairs from Columbia University, and is a Master’s of International Policy candidate at Texas A&M University.

Image: Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock