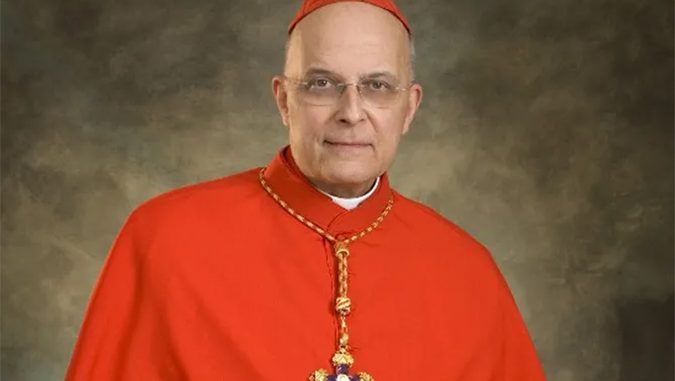

Holy Thursday, April 17, marked the tenth anniversary of Cardinal Francis George’s death after a lengthy battle with cancer. In the past decade, Catholics—especially American Catholics—have suffered from his absence. With his keen intellect, deep faith, personal holiness, and incisive prose, Cardinal George was a steady rudder.

Those gifts have been missed in this last decade of chaos and craziness in both the world and the Church. While Cardinal George would be too old to vote in the current papal conclave, his vision would be helpful as the cardinal-electors elect a new Pope. God had different plans and called Cardinal George home, and thus we’ve had to navigate these years without his sure guidance. But we can still learn much from his life and work. His witness provides ballast in these difficult times.

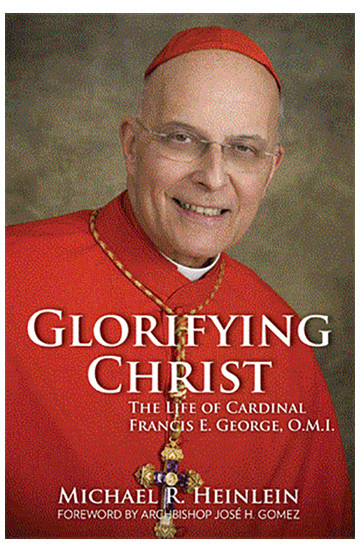

To that end, Michael R. Heinlein has given us a great gift with his seminal biography Glorifying Christ: The Life of Cardinal Francis E. George, O.M.I. Glorifying Christ, a work of scholarship, love, dedication, and excellence. That it has not received more attention is a shame. Heinlein painstakingly researched his subject, reviewed the archival material, and interviewed the relevant players. This is not hagiography. It is a serious biography at its best.

George was a Chicago boy who dreamed of giving his life to Christ as a priest of the Archdiocese. That dream ran aground in December 1950 when young Frannie George was stricken with polio. While George was admitted to Archbishop Quigley High School Seminary, the archdiocesan seminary, archdiocesan authorities made it clear that he would never be ordained. A chance introduction to the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate and a visit from their vocations director, who promised him he could be ordained if he walked across the room, reopened the door to the priesthood.

So, George entered the Oblates. The Oblates formed George to have a missionary heart. For George, this largely, though not exclusively, took the form of intellectual evangelization—doctorates in philosophy and theology and teaching—and order leadership—helping to guide the Oblates after the Second Vatican Council. Then, improbably, George was plucked from this missionary work to become a bishop, first of Yakima, WA, for six years, then Archbishop of Portland, OR, for under a year, and finally, Archbishop of Chicago from 1997 through his retirement in 2014.

The details beyond those broad outlines, which Heinlein so ably fills out, are what makes Glorifying Christ so compelling. While there are numerous themes on which one could dwell, there are a few that I’ll highlight here. For the rest, you’ll need to buy the book.

First is the concept of unity in truth. Both as an Oblate-Priest and later as a bishop, Cardinal George understood his role and that of the Church to draw all humanity—and the entire cosmos—together into unity with God and the Truth. It is remarkable how insistent and consistent Cardinal George was about this theme. Like Pope Benedict XVI and the theme of the creative Logos at the heart of the world, Cardinal George returned again and again to the idea of unity. As Heinlein states, “One of George’s main goals in ministry, both as a missionary and as a bishop was unity—unity in Christ but also unity within the human race in Christ.” Cardinal George wrote, “All things in the cosmos exist in a communio with one another precisely because they are rooted in a more primordial communio with the creator God.”

Second is the understanding of what and who the Truth is. The Truth is not an abstraction. The Truth has a name and a human face: Jesus Christ. Heinlein highlights a letter George wrote during the post-Council crisis about an Oblate seeking laicization. According to George’s observations, the Oblate “always spoke in terms of devotion to ministry, to a function, rather than to Christ as a person.” For George, this turned things on their head. For George, priestly “consecration is first of all to a Person, not to a particular job or role or cause . . . [W]hat matters [for priests] is if their love was for a Person, Christ as Lord and Savior, rather than for an idea (which turns out to be their own anyway) or a role or status or even a service (ministry).” And George’s understanding of the Church followed from this: “The Church points only to Christ, and anything that gets in the way of that proclamation weakens her mission.” In response to a question of what kept him going, George replied:

Well, Jesus Christ, of course. I think if one falls in love with the Lord, and permits himself to be embraced by the Lord, so that your whole life is a series of transformations, of conversions big and little, then there’s this certain security that enables you to continue when things aren’t so good, remembering the good times and the bad times.

Third is Cardinal George’s understanding of the Second Vatican Council as a radically Christocentric event. This theme is particularly timely as we see renewed struggles over the meaning and value of the Council. There are many, seemingly more each day, who would jettison the Council as a quasi-modernist disastrous detour for the Church. There are others, emboldened in recent years, who think the Council was Zero Hour, ushering in a Church of perpetual liquidity and the continued—and seemingly continuous—relitigation of questions asked and answered. (These latter certainly give fuel to the former.) For Cardinal George, these are “conflicts that distract Catholics from attending to the reason the Council was called: the conversion of the world.” Even in the early years after the Council, as a young priest and then-leader in the Oblates, Cardinal George rejected such narrow views of the Council, adopting what Pope Benedict would later describe as the “‘hermeneutic of reform,’ of renewal in the continuity of the one subject-Church.”

Fourth is the theme of suffering as redemptive in nature. Suffering was not an abstraction for Cardinal George. It wasn’t something that he knew only from tidy theological musings and learned tomes. It was something George lived. Cardinal George understood that each vocation participates in the cross. As he stated in 1997, “Christianity without the cross is a false religion.” And his vocation had its share of the cross. The initial and most prominent cross of his life was his bout with polio in 1950. George would suffer the effects of polio throughout his life, walking with a limp, and falling during liturgies with some frequency.

But the effects of polio were not his only sufferings. Shepherding the unruly and expansive Church in Chicago was also very much a suffering for Cardinal George. As Heinlein describes, “For George, serving as archbishop of Chicago was not so much a position to relish as it was a cross to bear.” Some of George’s private journal entries are striking in the profound pain and loneliness George experienced leading the Chicago archdiocese. Here one hears echoes of some of the abandonment expressed by St. Teresa of Calcutta in her journals.

Then there were George’s bouts with cancer. The bladder cancer, with which George was diagnosed in 2006, was serious and required significant surgery, radical cystectomy. As his doctor, Jesuit Myles Sheehan noted, the surgery “literally” required the rearrangement of his insides. And cancer returned in 2012 and killed him in 2015. While Cardinal George certainly did not minimize the very real pain from these sufferings, he also believed that suffering, rightly understood, could be a gift leading one to a deeper relationship with Christ and a personal transformation. As George would state at the 50th anniversary of his ordination, “You do things with those illnesses. Even illness can be a gift in some way.”

There are many other themes from Heinlein’s brilliant biography that one could focus on: George’s contribution to liturgical renewal and the new—and much richer and accurate—English translation of the Novus Ordo that the English-speaking Church began using in Advent 2010; George’s efforts to build and evangelize culture; his understanding of law as shaper of culture; his deep concern for the poor, the sick, and the suffering; his love of the priesthood and priests; and George’s important role as President of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

But the fifth and final theme I will discuss is Cardinal George’s understanding of Catholicism as a mediating force and a mediation between poles.

For George, Catholicism is neither liberal nor conservative, it is not ideological. Rather, it is a new way of life proposed by Christ and shepherded by the Church and nurtured by her sacraments. George understood the Church to be “where you go when you want to be free.” Throughout his life, Cardinal George worked to propose the Church as something above and separate from the limiting categories—political and otherwise—of the world. George bristled against such reductive views of the Church and the bishop. In response, he proposed a robust, alternative vision: “Jesus doesn’t talk about being conservative or being liberal. He talks about knowing the truth or living in darkness. It is true and false that define our internal dynamics and not politics or law directly.”

In George’s famous homily-turned-article, “How Liberalism Fails the Church,” he stated:

Liberal Catholicism is an exhausted project. Essentially a critique, even a necessary critique at one point in our history, it is now parasitical on a substance that no longer exists. It has shown itself unable to pass on the faith in its integrity and inadequate, therefore, in fostering the joyful self-surrender called for in Christian marriage, in consecrated life, in ordained priesthood. It no longer gives life.

He continued, saying that the “answer, however, is not to be found in a type of conservative Catholicism obsessed with particular practices and so sectarian in its outlook that it cannot serve as a sign of unity of all peoples in Christ.” Rather, the answer is:

[S]imply Catholicism, in all its fullness and depth, a faith able to distinguish itself from any culture and yet able to engage and transform them all, a faith joyful in all the gifts Christ wants to give us and open to the whole world he died to save. The Catholic faith shapes a church with a lot of room for differences in pastoral approach, for discussion and debate, for initiatives as various as the people whom God loves. But, more profoundly, the faith shapes a church which knows her Lord and knows her own identity, a church able to distinguish between what fits into the tradition that unites her to Christ and what is a false start or a distorting thesis, a church united here and now because she is always one with the church throughout the ages and with the saints in heaven.

Simply Catholicism. George understood his role as bishop to be the proclamation and fostering of this vision of Catholicism—the Church and Catholicism as a new way of seeing and living in the world.

Glorifying Christ reminds us of the gift we had—and have—in Cardinal George and his vision of the Church and Catholicism. One hopes the book and its subject can help inspire another generation of Catholic disciples and the cardinals gathered now in Rome.

Glorifying Christ: The Life of Cardinal Francis E. George, O.M.I. Glorifying Christ

By Michael R. Heinlein

Our Sunday Visitor, 2023

Hardcover, 520 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.